THE COURT OF APPEAL

COURT OF APPEAL RECORD No: 2024/188

HIGH COURT RECORD No: 2024/969SS

Neutral Citation: [2025] IECA 30

MacGrath J.

Hyland J.

McDonald J.

BETWEEN/

A.A. (ANONYMISED)

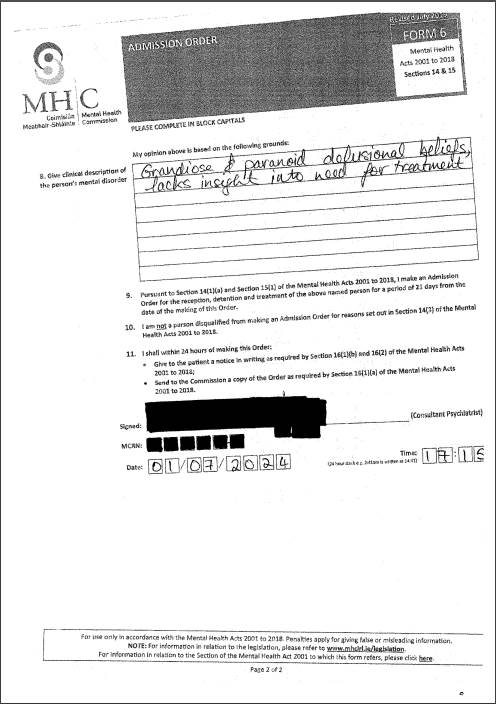

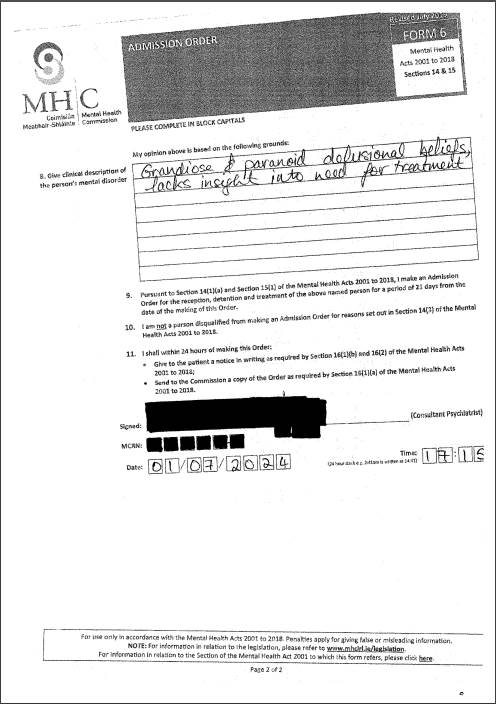

RESPONDENT/APPLICANT

- AND -

CLINICAL DIRECTOR OF THE ASHLIN CENTRE

APPELLANT/RESPONDENT

JUDGMENT of Ms. Justice Hyland delivered on the 17th day of February 2025

Introduction

1. This appeal from the decision of Simons J. of 3 July 2024 [2024] IEHC 408 in the context of an Article 40.4 inquiry concerns a net but important question: what are the obligations of those making an application under section 9, and an admission order under s.14, of the Mental Health Act 2001 as amended (the "2001 Act"), to explain the basis for their decision? The question arises in the context of an application for an inquiry pursuant to the provisions of Article 40.4.2 of the Constitution into the lawfulness of the detention of the respondent to this appeal under s.14(1) of the 2001 Act. (For the sake of clarity, the respondent to this appeal will be referred to as "Ms. A" and the appellant as the "approved centre" in this judgment.)

2. Section 14 provides for the involuntary admission of a person to an approved centre under the regime prescribed by the 2001 Act following the making of an admission order. Any such admission order may last up to 21 days. It is therefore an order that manifestly impacts upon the right to liberty of the person so detained.

3. Ms. A brought an application under Article 40.4.2 seeking a quashing of the admission order the day after it was made. An inquiry was directed into her detention on 2 July 2024 and was heard the following day. Following that hearing (where the consultant psychiatrist who had completed the form gave oral evidence), Simons J. gave a detailed ex tempore judgment where he made an Order directing the release of Ms. A. That decision was appealed by the Ashlin Centre, the approved centre to which Ms. A was admitted. In fact, it is agreed by both parties that the matter is moot because Ms. A was discharged from the approved centre following the Order and the admission order is spent. Ms. A has indicated she does not wish to play any part in this appeal.

4. Nonetheless, both parties have urged the Court to deal with the matter despite its mootness, given the systemic importance of the question raised and determined in the judgment of Simons J., i.e. the extent to which persons completing the requisite forms when making an application or admission order are required to explain the basis for same. I share the views of the parties that this is a question that goes well beyond the particular facts of this case, since it potentially affects every application and admission order made under the 2001 Act. Accordingly, it is a matter of some public interest. It therefore meets the criteria identified in the case law on mootness, most recently in Odum v. Minister for Justice [2023] 2 ILRM 164 and In the matter of KK [2024] IECA 242, that identify the circumstances in which a moot case ought nonetheless be determined.

Summary of Findings

5. The process of involuntary admission is a three-step process: an application to a registered medical practitioner for a recommendation for the person's involuntary admission under s.9; a recommendation from that registered medical practitioner for the person's involuntary admission under s.10; and the making of an admission order detaining the person in the approved centre under s.14.

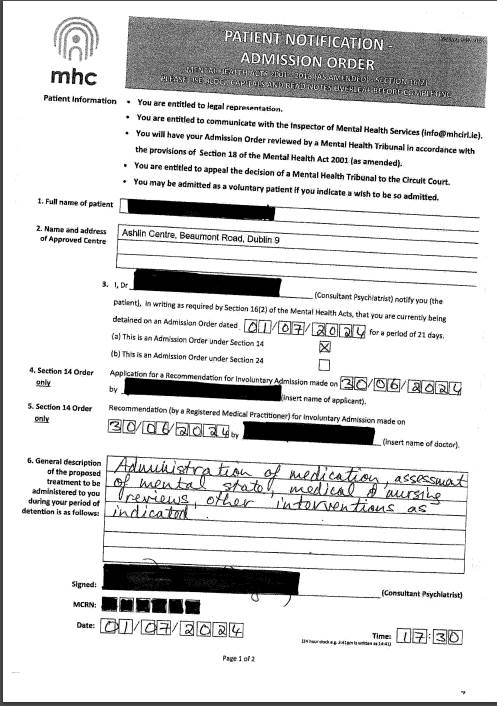

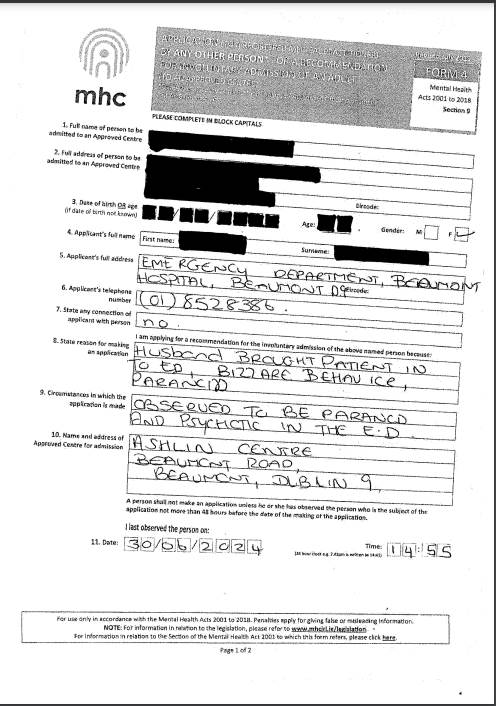

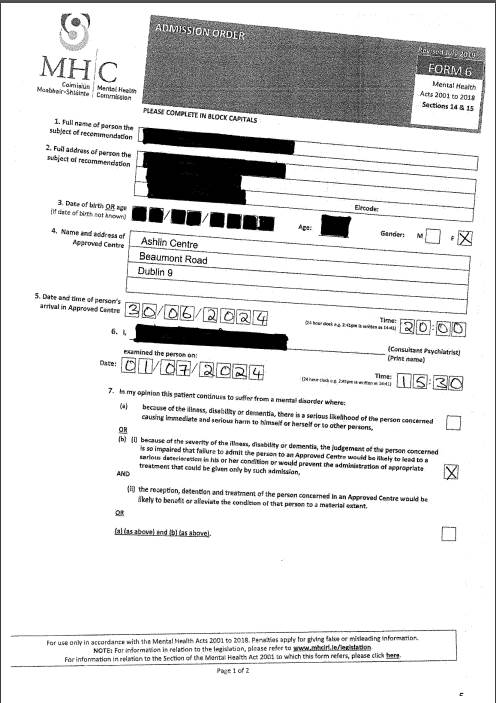

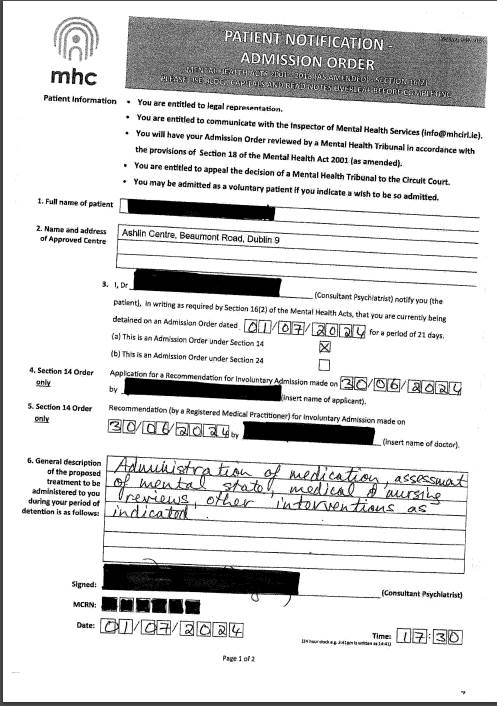

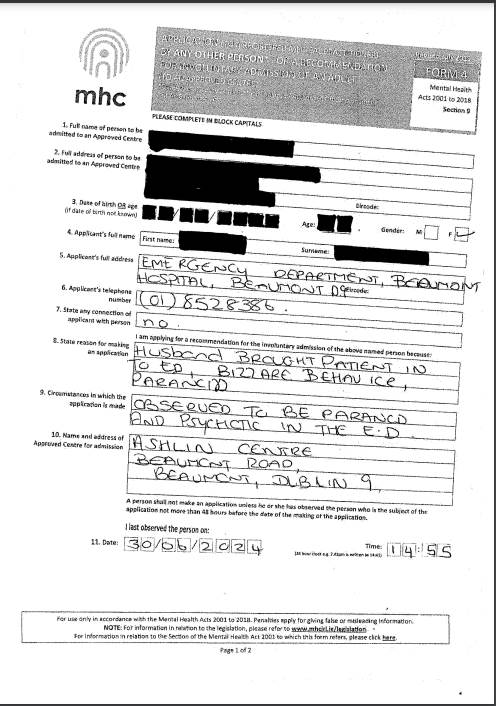

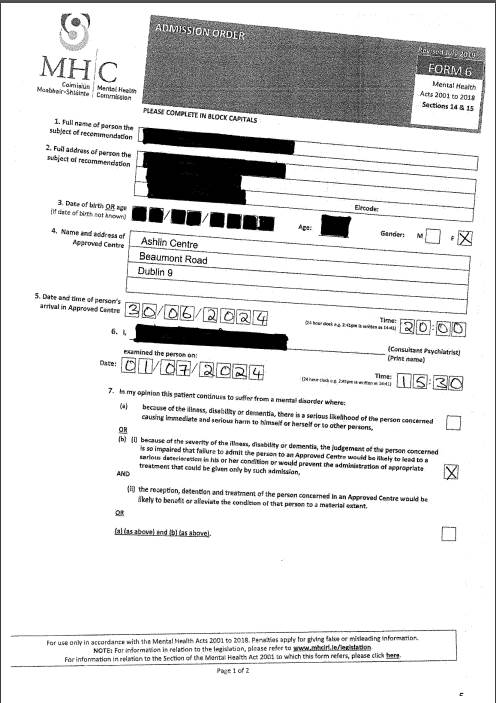

6. Section 14 provides that an admission order detaining a person on an involuntary basis must be made in a form specified by the Mental Health Commission (the "Commission"). Similarly, Section 9 requires that an application shall be made in a form specified by the Commission. The Commission has prescribed various forms: Form 6 is used for the making of an admission order and Form 4 is used for an application of the type made in this case. A completed Form 6 is the admission order.

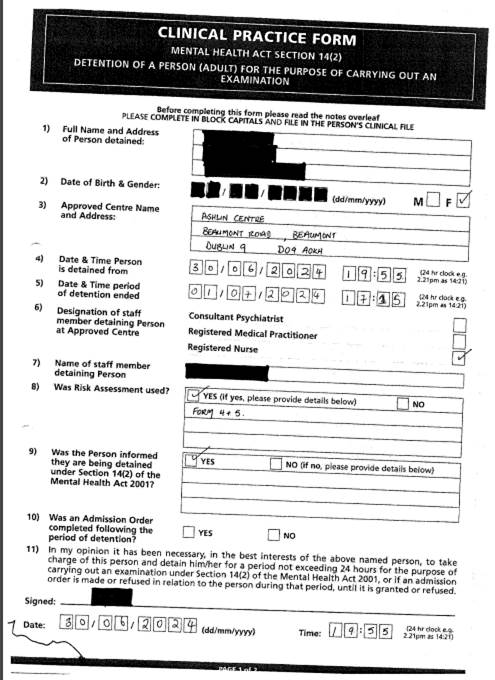

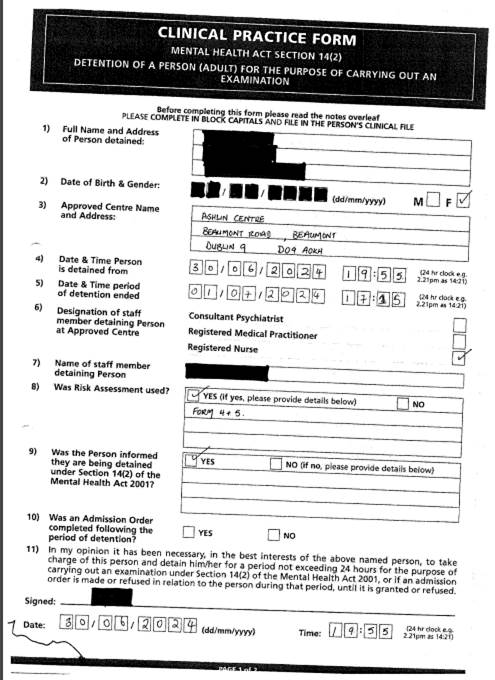

7. It is not necessary to decide this appeal on the basis of a duty to give reasons. Rather, it may be decided by considering whether there was compliance with the obligation to complete the statutory forms prescribed by the Commission, in particular Form 6.

8. Only where a consultant psychiatrist is of the opinion that a person has a mental disorder may that person be the subject of an involuntary detention order under s.14. The term "mental disorder", as defined by s.3(1), has a complex definition that requires the psychiatrist to be satisfied of a number of discrete matters. By requiring at Box 8 of Form 6 that the psychiatrist "state the grounds for the opinion that the person continues to suffer from a mental disorder" and "give a clinical description of the mental disorder", the Commission is requiring the psychiatrist to address - whether directly or by implication - the different aspects of the definition. The psychiatrist must show that they have stepped through each aspect of the statutory definition. Inferences and/or shorthand are permissible within limits. Language that does not explicitly address the statutory criteria, but when read in context implies a consideration of the statutory criteria may be treated as sufficient grounds for the opinion. For example a psychiatrist may identify symptoms that permit an obvious inference to be drawn that the person continues to suffer from a "mental illness", this being one aspect of the definition of a mental disorder.

9. The grounds given in this case did not address each aspect of the statutory definition. Box 8 was completed as follows: "grandiose & paranoid delusional beliefs, lacks insight into need for treatment". The reference to "grandiose, paranoid and delusional beliefs" constituted sufficient grounds for the psychiatrist's conclusion that Ms. A had a mental illness. The reference to "lacks insight into need for treatment" may be interpreted as signifying that the psychiatrist had formed the opinion that the lack of insight would prevent the provision of treatment in the community and that therefore the second part of s.3(1)(b)(i) was met i.e. failure to admit to the approved centre would prevent the administration of appropriate treatment. But there is no material at all identifying the grounds for the psychiatrist's opinion that s.3(1)(b)(ii) was met i.e. that the reception, detention and treatment of Ms. A in the approved centre would be likely to benefit or alleviate her condition to a material extent. Box 8 was not completed as required by the terms of Form 6. As a result the admission order was invalidated, and did not provide a basis to detain Ms. A.

10. On the other hand, Form 4, used to make the application to detain Ms. A, was completed in a compliant fashion. An application may be made by four categories of persons under the Act, one of which is "any other person" - the applicable category in this case. Section 9 provides that where an application is made by "any other person" the application shall contain a statement of the reasons why it is so made, of the connection of the applicant with the person to whom the application relates, and of the circumstances in which the application is made. This is to ensure only persons with an appropriate interest in the well-being of a person with a suspected mental disorder have the power to trigger a process under the 2001 Act. It is necessary to explain in Form 4 why they are making the application but it is not necessary to explain why none of the other persons who can make an application - a spouse, civil partner or relative; or authorised officer; or a member of An Garda Síochána, - are doing so. Here, there was sufficient information provided on Form 4 to make clear the identity of the applicant, why she was making the application and why it was appropriate for her to do so as opposed to any other person.

Statutory Framework

11. As has been observed in a number of cases concerned with the operation of the 2001 Act, the Act establishes an elaborate statutory regime designed to ensure that the deprivation of liberty inherent in an involuntary admission to an approved centre is carried out pursuant to a system of checks and balances - see for example O'Donnell J. in B.G. v. The Clinical Director [2024] IEHC 643, where he observed that the Oireachtas has framed the overall structure of the 2001 Act in a way that gives rise to:

"A coherent and interlocking network of checks and balances that seek to accommodate the rights of individuals to autonomy, dignity and privacy, with the public interest in ensuring that medical care is available to potentially highly vulnerable and unwell persons, who because of the effects of their particular presenting illness are unable to access medical treatment voluntarily."

12. The various statutory provisions relevant to the questions raised by this appeal are set out, and discussed, later in this judgment. However, it is important to briefly describe the process that led to the involuntary admission of Ms. A under s.14 in order to understand the steps leading up to an admission order. I am grateful to Phelan J. for setting out that process in her judgment in A.R. v Department of Psychiatry of Connolly Hospital [2024] IEHC 440: my summary below, modified to address the facts of this particular case, draws heavily on her description.

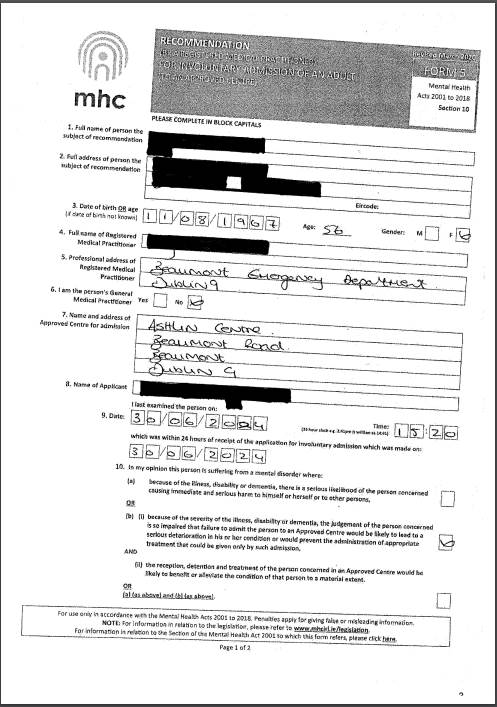

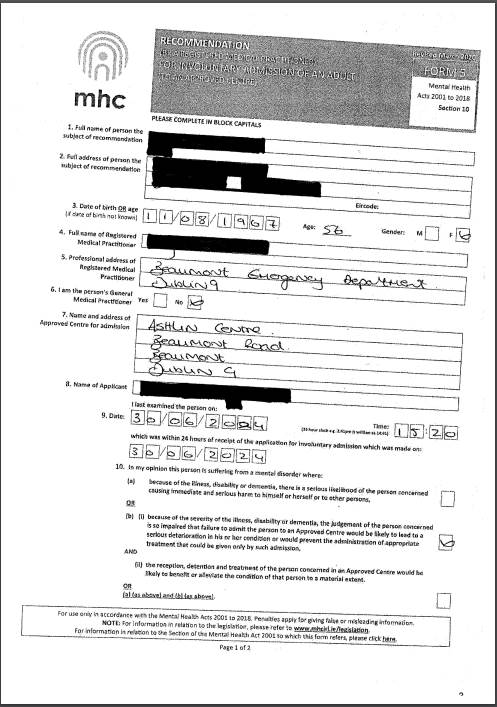

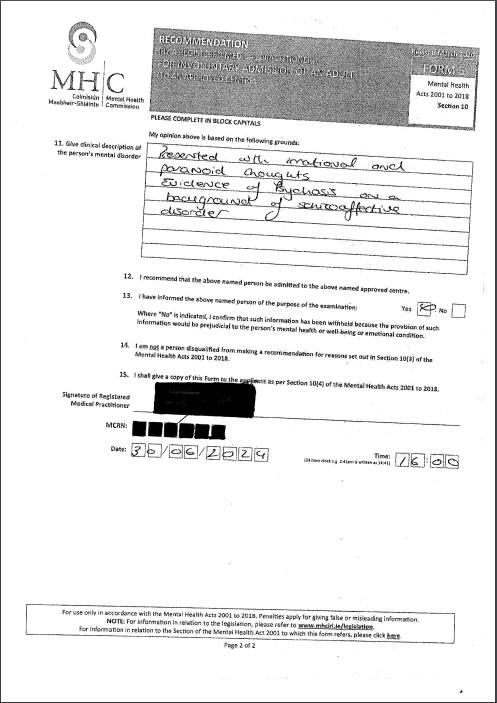

13. The process of involuntary admission is a three-step process: an application under s.9 to a registered medical practitioner for a recommendation for the person's involuntary admission; a recommendation under s.10 from that registered medical practitioner for the person's involuntary admission; and the making of an admission order detaining the person in the approved centre under s.14. A person may be detained in the approved centre for 24 hours following the making of a recommendation to allow an examination of the person by the consultant psychiatrist. If an admission order is made, it will be made by the consultant psychiatrist who has examined the person. The application, recommendation and admission order must be in a form specified by the Commission. The Commission has prescribed forms for this purpose: Form 4 was used in the instant case for the application, as it relates to applications by "any other person"; Form 5 is the form designated for the making of a recommendation under s.10; and Form 6 is the form used for the making of an admission order. A completed Form 6 is itself the admission order.

14. Section 9 of the 2001 Act sets out the categories of persons who may apply for involuntary admission, including at s. 9(1)(d), "any other person". The applicant for the recommendation in this case, a nurse in the emergency department in Beaumont Hospital, fell into that category. Section 9(5) requires that reasons must be given where the person making the application comes within the definition of "any other person".

15. An application under s.9 is made to a registered medical practitioner, who must examine the person the subject of the application. If the medical practitioner is satisfied following that examination that the person is suffering from a mental disorder, the medical practitioner shall make a recommendation for that person's involuntary admission to an approved centre pursuant to s.10 of the 2001 Act.

16. Under s.13, where a recommendation is made, the applicant concerned shall arrange for the removal of the person to the specified approved centre. Where the recommendation is received by the clinical director of an approved centre, a consultant psychiatrist on the staff of the centre is obliged to carry out the duties provided for by s.14(1) of the 2001 Act, as discussed in detail below, which include an examination of the person.

17. Section 14(2) of the 2001 Act allows a person being examined under s.14(1) to be detained by the consultant psychiatrist, a medical practitioner or a registered nurse on the staff of the approved centre for the purpose of carrying out the examination but limits the permitted period of detention to a period not exceeding 24 hours.

18. Section 16 provides for specified information to be given to persons admitted to an approved centre. There is no requirement under the 2001 Act to provide a copy of Statutory Forms 4, 5 and 6 at issue in these proceedings to the person detained.

19. Section 17 of the 2001 Act provides for the mandatory review of, inter alia, an admission order, before a Mental Health Tribunal (a "tribunal") established by the Commission. It also provides for the appointment of an independent consultant psychiatrist, whose report, following independent examination of the person detained and their medical records, shall be available to the tribunal reviewing the involuntary detention.

20. Section 18 of the 2001 Act provides for the duties and powers of the tribunal when reviewing an admission or renewal order, including requiring the tribunal to provide reasons for its decision. As observed by Phelan J. in A.R.:

"In common with s.9(5), s.18(5) of the 2001 Act makes express statutory provision for the giving of reasons. No similar provision is made in respect of a recommendation under s.10 or an admission order under s.14. The requirement for the specification of reasons in ss.9(5) and 18(5) but not elsewhere may be of some consequence insofar as it reflects a deliberate legislative intention whereby the Legislature provides for the giving of reasons in specific circumstances but not otherwise. It is noteworthy also that in the way this distinction exists, the Legislature distinguishes between a situation where clinical judgment is exercised (as in the exercise of a power under ss. 10 and 14 where no duty to give reasons is specified in the statutory provisions) and those where an administrative or quasi-judicial power is in question such as in s. 18(5), where a duty to give reasons in writing is clearly prescribed."

Factual background

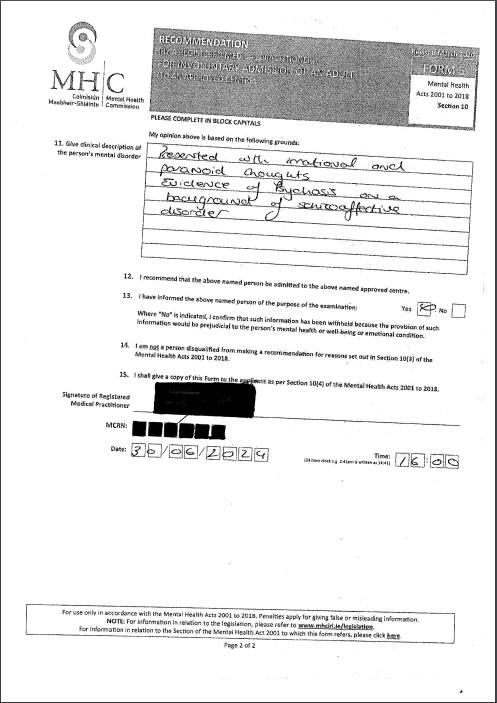

21. Ms. A is a woman in her fifties with a history of schizoaffective disorder. On 30 June 2024, she was brought to the emergency department of Beaumont Hospital by her husband. Upon presentation to the hospital, Ms. A was examined by a nurse at the emergency department who made an application under s.9, filling out the requisite Form 4 at approximately 15:00 hours, in which it was stated that "husband brought patient in to ED, bizarre behaviour, paranoid", and that Ms. A was "observed to be paranoid and psychotic in the ED". At roughly 16:00 hours, Dr. McK, a medical practitioner in the same emergency department, made a recommendation under s.10 by completing Form 5. Dr McKenna indicated on the form that in his opinion Ms. A suffered from a mental disorder, and provided the basis for his opinion as follows: "presented with irrational and paranoid thoughts. Evidence of psychosis on a background of schizoaffective disorder."

22. Ms. A was conveyed to the approved centre, located in the grounds of Beaumont Hospital, arrived at roughly 20:00 hours on 30 June 2024 and was detained pursuant to s.14(2) of the 2001 Act for the purposes of carrying out a medical examination. The next day, 1 July 2024, at roughly 15:30, Ms. A was examined by a consultant psychiatrist, Dr. Q, and at 17.15 she was involuntarily admitted to the approved centre following the completion of Form 6 i.e. the admission order. Box 8 of the Form (discussed in detail below) recorded the following: "grandiose & paranoid delusional beliefs, lacks insight into need for treatment". At 17:30, Ms. A was furnished with a Patient Notification - Admission Order, pursuant to s.16(2) of the 2001 Act, which informed her that she was being detained and notified her of her statutory rights and the proposed course of treatment.

23. Ms. A made an application for an inquiry under Article 40.4.2 of the Constitution on 2 July, following which Simons J. directed an inquiry into Ms. A's detention. The inquiry was held on 3 July 2024 at which Ms. A was legally represented. Dr. Q gave oral evidence to the inquiry. Simons J. gave a detailed and comprehensive ex tempore ruling which was later typed up and circulated to the parties. He ordered that the grounds for detention i.e. the admission order made under s.14, was insufficient to justify the detention of Ms. A and directed that she be released forthwith from detention. A notice of appeal was filed on 30 July 2024. Ms. A's notice was filed on 14 November 2024.

Decision of the trial judge

24. The trial judge acknowledges that there is case law from the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal making it clear that there is an obligation on mental health tribunals to give reasons for their decisions and identifying the type of reasons that are required. That case law is entirely unsurprising; as noted above, s.18(5) of the 2001 Act identifies that notice in writing of the decision of the tribunal and the reasons therefor shall be given to identified persons, including the patient and his or her legal representative. Hardiman, J., referring to decisions of mental health tribunals, identified in M.D. v Clinical Director of St. Brendan's Hospital [2007] IESC 37, that this was an aspect of fair procedures.

25. The trial judge acknowledges that an admission order is "a very different animal to a decision of the mental health tribunal" and observes that it is not to be expected that any of the decision makers under the 2001 Act are required to engage in the same level of detailed reasoning as one would expect from the tribunal. But he concludes at para. 33 that they must nevertheless reach a minimal threshold of reasoning, and should indicate that they have properly considered and applied the statutory criteria. He observes it was not sufficient simply to recite the legislative provisions under the 2001 Act without making some attempt to explain how the statutory criteria are met. At para. 35, he observes that the admission order must be valid on its face, that a court or tribunal considering it must understand the basis upon which it has been reached, and that it is not sufficient simply to tick a box to indicate that certain statutory criteria have been met without in any way seeking to engage with or to explain how those statutory criteria have been fulfilled. He adds that the requirement that reasons must be stated is not merely for the High Court or tribunal, but also to allow the person who has been involuntarily detained to know the precise basis upon which their liberty has been taken away.

26. The trial judge finds that it was necessary to explain at Box 8 of Form 6 the clinical description of the person's mental disorder. At para. 35, he finds that it was necessary in the instant case for the consultant psychiatrist to diagnose the proposed patient with a mental illness at least on a preliminary basis and then identify whether there would likely be a serious deterioration in her condition without an involuntary admission, or alternatively that the administration of appropriate treatment would be prevented without an involuntary admission. He observes that that presupposes that the decision maker must identity appropriate treatment or the risk of serious deterioration. He notes that none of that is evident from the form of the admission order and the most that is done is to recite symptoms. He concludes that this comes nowhere close to meeting the statutory requirements.

27. At para. 38, the trial judge finds the admission order must display jurisdiction on its face and must indicate that the consultant psychiatrist understood and engaged with the statutory criteria. At para. 39 he refers to the forms prescribed by the Commission and to Box 8 of Form 6, which requires a description of the mental disorder, with, as he puts it, "all of the baggage that the test under s.3 of the Mental Health Act 2001 requires".

28. At para. 40 he considers the completed Form 4 in this case, noting that it came nowhere close to meeting the statutory requirement, that it did not explain at all why an involuntary admission may have been required but referred to symptoms only, and concludes that no explanation or potential justification were given as to why what he refers to as "the draconian step" of applying for involuntary admission had been taken.

Core dispute between the parties

29. The differing approaches of the parties may be summarised in the following way. Counsel for Ms. A argued that, whether one characterises it as a duty to give reasons or an obligation to demonstrate that the statutory criteria have been met, a psychiatrist making an admission order and/or a person applying for a recommendation, must set out on the face of the form prescribed by the Commission the basis upon which they have come to the conclusion that the statutory requirements are met. This does not amount to a requirement that the person completing the form must give a detailed clinical description of the condition the person is suffering from, but rather that the description is sufficient to permit an evaluation of why the person considers the statutory conditions are met. Counsel for Ms. A conceded that this need not always be explicit, and that compliance with the statutory conditions may at times be implied from the language used; but argues that, in the instant case, there was insufficient detail in the forms to conclude that the statutory requirements had been met.

30. Counsel for the approved centre, on the other hand, contended that it is not for a court carrying out an Article 40.4 inquiry to consider the clinical merits of the decision of the psychiatrist to make an admission order and that therefore there is no obligation to explain the basis upon which the psychiatrist came to the view that the person was suffering from a mental disorder, which view justifies the making of an admission order. In support of this submission, he pointed out that neither a tribunal nor the Circuit Court on appeal has the function of considering whether a patient had a mental disorder at the date of the making of the admission order, and therefore the reasons for the making of that order are not necessary for the exercise by the tribunal or the Circuit Court of their functions. Nor, it was argued, is the person the subject of the admission order entitled to see the completed Form 6 that constitutes the admission order and therefore the non-provision of reasons may be justified on this basis. Counsel relied on s. 16 of the 2001 Act which prescribes the information required to be given to a person the subject of an admission order, and argued that this represents the extent of the requirement to give an explanation for the decision. On that analysis, the manner in which the form was completed was satisfactory.

Statutory Forms

31. It is fair to characterise the decision of the trial judge as one that identifies an obligation to give reasons for the making of an admission order and application, and directs the release of Ms. A on the basis that inadequate reasons were given, thus invalidating the admission order that detained her. Submissions were made by both parties as to the relevance of the well-established obligation in administrative law to give reasons, and whether it applies at all in this context. More glancing submissions were made by counsel for Ms. A to the effect that there was a wider obligation of fair procedures that necessitated reasons for the admission order.

32. The latter argument can be swiftly addressed. In Blehein v. St. John of God Hospital [2002] IESC 43, the applicant was seeking to challenge, inter alia, the legality of various periods of detention spent in St. John of God hospital. He argued that the procedure adopted in receiving and taking charge of him when he was admitted was in breach of his constitutional rights to fair procedures and his right to have notice of the intended detention and grounds upon which he would be detained, his right to consult a lawyer and his own medical practitioner, and to be heard in advance of being detained.

33. The High Court held that it would be inconsistent with the operation of the statutory provisions to impose upon them the further mechanisms of audi alteram partem or other quasi-judicial procedures. O'Sullivan J. observed that the legislature has entrusted the initiation of this mechanism to the professional judgment of two medical practitioners and the mechanism to be employed is a matter for the legislature. McGuinness J. in the Supreme Court endorsed this reasoning, noting that the legislation used for detaining persons in hospital is designed to deal with a situation where persons are suffering from serious mental illness, and pointed out that if the procedural steps sought by the applicant were to be required in all cases, the legislation would swiftly become unworkable. She observed that the detention provisions involve considerable encroachment on the ill person's constitutional rights, in particular the right to liberty which must be balanced against the ill person's need for both protection and treatment.

34. The argument made by counsel for Ms. A did not go so far as that made in Blehein: the height of it appears to be that detailed reasons are required to be given in order to ensure adherence to fair procedure principles. Nonetheless, the argument is grounded upon the premise that fair procedures are required to be observed when detaining a person under the 2001 Act, with all of the steps that might potentially involve, including a right to be heard, a right to legal representation, a right to a reasoned decision and so on. As a matter of first principles, that appears incompatible with the detailed legislative regime established by the 2001 Act, which includes a review of the detention within a prescribed period of time. At that review, the detained person has the right to legal representation, the right to be heard, the right to reasons for the decision and other associated rights.

35. Nor was that argument accepted in Blehein. The Supreme Court accepted that the regime under the 1945 Act was designed to balance the competing rights at issue in any detention for treatment and rejected the argument that fair procedure rights should be laid on top of the existing legislative structure. That analysis applies with even greater force in the context of the 2001 Act which introduced a raft of new measures designed to provide additional protection for detained persons. For those reasons, any argument based on a free standing right to fair procedures divorced from the legislative structure established by the Oireachtas, must fail.

36. In respect of the duty to give reasons, I do not consider it necessary to decide this appeal on that basis. Rather, it can be decided on the more confined basis of the statutory obligation imposed by the 2001 Act to complete the forms prescribed by the Commission in accordance with their terms. This in turn requires a consideration of the origin of the forms, and their foundation in a statutory context. As noted above, s.9 is concerned with the application process. Section 9(3) provides as follows: "An application shall be made in a form specified by the Commission". Similarly, s.10(1) provides that where a registered medical practitioner is satisfied following an examination of the person the subject of the application that the person is suffering from a mental disorder, he or she shall make a recommendation "in a form specified by the Commission". (I have not discussed the completed Form 5 given that the recommendation was not the subject of challenge in these proceedings).

37. Section 14 is in the following terms: -

"(1) Where a recommendation in relation to a person the subject of an application is received by the clinical director of an approved centre, a consultant psychiatrist on the staff of the approved centre shall, as soon as may be, carry out an examination of the person and shall thereupon either—

(a) if he or she is satisfied that the person is suffering from a mental disorder, make an order to be known as an involuntary admission order and referred to in this Act as "an admission order" in a form specified by the Commission (emphasis added) for the reception, detention and treatment of the person and a person to whom an admission order relates is referred to in this Act as "a patient", or

(b) if he or she is not so satisfied, refuse to make such order."

38. The definitions section of the Act provides that "admission order" shall be construed in accordance with s.14. Interestingly, the precursor to the 2001 Act, the Mental Treatment Act 1945, contained a provision whereby regulations could be made by the Minister specifying the forms to be used. That approach was not replicated in the 2001 Act: rather, the function of specifying forms was given to the Commission. But s.14(1) makes it clear that only an admission order made in the form specified by the Commission is a valid admission order. That is part of the checks and balances created by the 2001 Act. It underscores the importance of Form 6; and the necessity for completing it in accordance with the terms specified by the Commission given that a completed Form 6 is the admission order. As observed by O'Donnell J. in B.G., "... it is possible to understand the relevant forms - whose format the Oireachtas has expressly delegated to the expertise of the Commission - as constituting primary and important evidence of how the processes have been carried out." (para. 44).

39. Separately, the obligations on a person who has completed a form, whether for an admission order, a recommendation or an application for a recommendation, are specified by the Act. Section 16 provides as follows: -

"(1) Where a consultant psychiatrist makes an admission order or a renewal order, he or she shall, not later than 24 hours thereafter -

(a) send a copy of the order to the Commission, and

(b) give notice in writing of the making of the order to the patient."

40. Section 16(3) provides that references to an admission order in s.16 shall include references to the relevant recommendation and the relevant application.

41. The receipt of an admission order by the Commission sets in train a series of events. Under s.17, the Commission must refer an admission order or renewal order to a tribunal, which is established to review the admission order. Section 17(1)(c)(iii) provides that the Commission shall direct in writing a member of the panel of consultant psychiatrists to, inter alia, review the records relating to the patient in order to determine whether the patient is suffering from a mental disorder. Those records will include the admission order and the forms used for the application and recommendation.

42. Next, it is necessary to consider the requirements of the relevant forms. For ease of reference, the forms as completed in this case are contained in Appendix 1 to this judgment. The first form is entitled "Form 4", being an application to a registered medical practitioner by any other person for a recommendation for involuntary admission of an adult to an approved centre. The heading refers to the "Mental Health Acts 2001-2018 section 9 revised July 2019". The term "any other person" is qualified as follows: "other than a spouse/ civil partner/ relative/ authorised officer or member of An Garda Síochána". At Box 7, the side note requires the person to state any connection of applicant with the person. At Box 8, there is a side note as follows: "State reason for making an application". Above Box 8, the following appears: "I am applying for a recommendation for the involuntary admission of the above-named person because:". Box 9 has the following side note: "Circumstances in which the application is made".

43. The seriousness with which the completion of these forms is taken is identified in a footnote which identifies as follows: "For use only in accordance with the Mental Health Acts 2001-2018. Penalties apply for giving false or misleading information." This presumably reflects s.9(6), which provides: "A person who, for the purposes of or in relation to an application, makes any statement which is to his or her knowledge false or misleading in any material particular, shall be guilty of an offence".

44. The applicable form for an admission order is Form 6. As with Form 4, Form 6 refers on its face to the relevant sections of the 2001 Act, being sections 14 and 15, and notes that it was revised in July 2019. A footnote again identifies that there are penalties for giving false or misleading information. There are 11 sections/boxes in total on the two-page form. Boxes 7 and 8 are of particular importance.

45. Box 7 sets out the definition of mental disorder as set out at s.3 of the 2001 Act and requires a consultant psychiatrist on the staff of the approved centre to confirm that they have considered whether the person continues to suffer from a mental disorder i.e. since the date the recommendation was made, and, if so, why they consider that to be the case, by reference to the definition of mental disorder. That confirmation is given by ticking one or more boxes.

46. Box 8 has a side note as follows "Give clinical description of the person's mental disorder". Above Box 8 are the following words "My opinion above is based on the following grounds:"

Definition of Mental Disorder under the Act

47. The term "mental disorder" at s.3(1) of the 2001 Act has a complex definition that requires the psychiatrist to be satisfied of a number of discrete matters. There are three alternative "pathways" within the definition. The matters that the psychiatrist must be satisfied of vary depends on the internal pathway followed. The definition is as follows:

"3.—(1) In this Act "mental disorder" means mental illness, severe dementia or significant intellectual disability where—"

(a) because of the illness, disability or dementia, there is a serious likelihood of the person concerned causing immediate and serious harm to himself or herself or to other persons, or

(b)(i) because of the severity of the illness, disability or dementia, the judgment of the person concerned is so impaired that failure to admit the person to an approved centre would be likely to lead to a serious deterioration in his or her condition or would prevent the administration of appropriate treatment that could be given only by such admission, and

(ii) the reception, detention and treatment of the person concerned in an approved centre would be likely to benefit or alleviate the condition of that person to a material extent."

48. The first issue the psychiatrist must satisfy themselves of is that the person has one or more of the following conditions: a mental illness, severe dementia or a significant intellectual disability. Definitions of those terms are contained in s.3(2) as follows:

"(2) In subsection (1)—

"mental illness" means a state of mind of a person which affects the person's thinking, perceiving, emotion or judgment and which seriously impairs the mental function of the person to the extent that he or she requires care or medical treatment in his or her own interest or in the interest of other persons;

"severe dementia" means a deterioration of the brain of a person which significantly impairs the intellectual function of the person thereby affecting thought, comprehension and memory and which includes severe psychiatric or behavioural symptoms such as physical aggression;

"significant intellectual disability" means a state of arrested or incomplete development of mind of a person which includes significant impairment of intelligence and social functioning and abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person."

49. I note that the definitions of severe dementia and significant intellectual disability contained in s.3(2) do not accord with how one might ordinarily interpret those words. The first part of the definition of severe dementia referring to the impairment of intellectual function is unremarkable; but the second part, i.e. the presence of severe psychiatric or behavioural symptoms such as physical aggression, would likely exclude many people with severe dementia. Similarly, a person will only meet the definition of significant intellectual disability if there is abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person. There are many thousands of people with significant intellectual disabilities who do not meet this definition. The definitions are presumably seeking to capture people who potentially require involuntary hospitalisation, subject to meeting the remainder of the definition of mental disorder.

50. For the purposes of s.14 of the Act, the consultant psychiatrist will have to carefully direct their mind to whether a person meets one or more of these three alternative criteria. At the appeal hearing, counsel for both parties made submissions on whether it was necessary for a consultant psychiatrist to decide when making an admission order which of the three categories a person fell into, and if so, whether it was necessary to identify same on the face of the admission order under Box 8. It was strongly argued by counsel for the approved centre that this was not the case, given that there is nothing on Form 6 identifying such a requirement. Further, he observed that there may be practical difficulties in so doing, given the relatively short amount of time a psychiatrist has to observe the patient who has been detained on foot of the recommendation, i.e. a maximum of 24 hours. Counsel for Ms. A, on the other hand, argued that it was a necessary precondition to determine which condition the person in question suffers from, and that must be identified on the form.

51. Section 14(1) simply requires that the psychiatrist be satisfied that the person is suffering from a mental disorder. The definition in s.3(1) (a) or (b) (discussed further below) requires that the person meets one or both definitions "because of the illness, disability or dementia". There is no requirement, either in s.3(1), or on the face of Form 6, that requires the psychiatrist to identify which of the three categories they believe the person falls into. Rather, they must be satisfied that the person falls into one or more of those categories and unless they are so satisfied, a person cannot be considered to have a mental disorder. As per the instructions on Form 6, at Box 8 they must give grounds for their opinion. That may be done by an identification of the category or categories the person falls into, i.e. they may explicitly identify that the person has a mental illness within the meaning of s.3(1), or by providing a diagnosis that, by implication, indicates they are satisfied that the person comes within one or more of the three categories, or by identifying symptoms that permits an obvious inference to be drawn that the person comes within one or more of the three categories. I cannot therefore agree that it is necessary to indicate at Box 8 which of the three conditions has been selected, provided one can understand from the grounds given for the psychiatrist's opinion that he or she has considered the issue and is satisfied that the person comes within one or more of the categories.

52. At para. 35 of the judgment of the High Court, the trial judge indicates that it is necessary that the psychiatrist diagnoses the patient with a mental illness, at least on a preliminary basis. To the extent that this sentence indicates that the psychiatrist must form a view that one or more conditions identified in s.3(1) are present, and that view must be discernible in the way I have described above from Form 6, then I agree. But that does not mean that the psychiatrist is obliged to arrive at a diagnosis of the person and identify same on Form 6: simply deciding a person has a mental illness within the meaning of s.3(2) is unlikely to be considered a diagnosis within the usual meaning of the term. Moreover, as pointed out by counsel for the approved centre, it may not be possible to arrive at a diagnosis within the 24 hour period available. There is no requirement to make a diagnosis in s.3(1) or in Form 6; rather, the psychiatrist must identify the grounds for their opinion that the person has a mental disorder as defined at s.3(1).

53. Having established that the person comes within one or more of the three categories described above, two alternative scenarios must next be considered. The first is what I will refer to as the "harm criteria" i.e. because of the illness, disability, or dementia, there is a serious likelihood of the person concerned causing immediate and serious harm to himself or herself or to other persons. It is addressed by s.3(1)(a).

54. The second is what I will refer to as the "treatment criteria", and has two constituent parts, both of which have to be satisfied. It is addressed by s.3(1)(b)(i) and (ii). The first is that, because of the severity of the illness, disability, or dementia, the judgement of the person is so impaired that failure to admit the person to an approved centre would be likely to lead to a serious deterioration in his or her condition or would prevent the administration of appropriate treatment that could only be given by such admission. That means there must be an evaluation of the severity of the illness, disability, or dementia and the extent to which it is impairing the person's judgement. Next, the psychiatrist must consider whether failure to admit would either likely lead to a deterioration or prevent the administration of appropriate treatment.

55. The tests contained within s.3(1)(b)(i) are separate and distinct. In other words, one could envisage a situation where the psychiatrist does not anticipate a serious deterioration absent admission, but does anticipate that without admission, appropriate treatment could not be given. Alternatively, a psychiatrist could come to the view that appropriate treatment could be given outside the hospital but even with such treatment, there would be a serious deterioration in the condition of the person and therefore admission is required. Even this brief discussion shows that these are relatively involved criteria and necessitate a close analysis of the person's situation by the psychiatrist.

56. After going through this analysis, and assuming the psychiatrist is satisfied that one or other (or possibly both) of the requirements in s.3(1)(b)(i) are met, they must consider an entirely separate issue under s.3(1)(b)(ii): whether the psychiatrist is of the opinion that the reception, detention and treatment of the person would be likely to benefit or alleviate the condition of that person to a material extent. In fact, at first glance, (b)(ii) appears somewhat duplicative of b(i), because it deals with the impact of the treatment on the person and that has already been addressed in b(i). However, a close reading of b(ii) demonstrates that not only does a psychiatrist have to look at whether there would be a deterioration absent admission, or whether the treatment could only be given in a hospital, but also whether that treatment would be likely to benefit or alleviate the condition to a material extent. In other words, it is not enough that the admission to the approved centre would prevent the person seriously deteriorating or enable treatment to be given. Rather, the psychiatrist must be of the opinion that the treatment in question would not merely, for example, maintain the status quo, but that it would actually benefit or alleviate the condition of the person.

Obligations on the psychiatrist when completing Form 6

57. A psychiatrist can only conclude a person has a mental disorder, thus permitting detention, where he or she has satisfied themselves that all of the various aspects of the definition of mental disorder have been met. Form 6 explicitly requires the psychiatrist to be satisfied that the person has a mental disorder and to explain whether that opinion has been reached on the basis of s.3(1)(a) or s.3(1)(b) by ticking the relevant boxes at Box 7. As noted above, Box 8 requires the psychiatrist to explain the grounds for their opinion that the person has a mental disorder and requires a clinical description of the mental disorder.

58. Recalling that under s.14, an admission order must be made in a form specified by the Commission, it follows that the psychiatrist is obliged to fill in the entirety of the form as designed by the Commission. A substantial failure to do so may invalidate the admission order, with the result that there is no legal basis for the detention. For that reason, it is necessary that an admission order must be completed in accordance with the form prescribed by the Commission as required by s.14(1).

59. The trial judge was very critical of the choice by the Commission to permit a psychiatrist to confirm the person has a mental disorder by ticking various boxes at section 7 of Form 6. But there is no challenge to the format of the Form, and indeed in my view none is warranted. The boxes at section 7 require the psychiatrist to select between the different pathways in the definition and indicate whether they think the harm criteria or the treatment criteria or both have been met. I agree with the observation of McCarthy J. in G.B. v The Mental Health Tribunal [2022] IECA 71 as follows:

"I am not persuaded that the completion of the forms amounts to a box ticking exercise as that term is used colloquially. The forms are solemn mandatory elements within the protective framework of the legislation which must be signed by the relevant person. In the case of medical practitioners, Forms 5 and 6 require the practitioner to express a very specific clinical view. The fact that this is expressed by choosing a box to tick does not detract from the fact that this involves the exercise and expression of a clinical judgment."

60. By requiring at Box 8 that the grounds for the opinion must be set out and a clinical description of the mental disorder given, the Commission is requiring the psychiatrist to address - whether directly or by implication - the different aspects of the definition. The psychiatrist must show that they have stepped through each aspect of the statutory definition. Thus, for example, if they have made the admission order on the basis of s.3(1)(a), they must show they have addressed themselves to the harm criteria. If, on the other hand, they have made it under s.3(1)(b), they must show, whether explicitly or by necessary implication, that they have addressed themselves to the treatment criteria i.e. they have considered the consequences of a failure to admit the person to the approved centre and are satisfied that it comes within one or other of the possibilities identified in b(i). Separately, they must show they have addressed their mind to the question of whether the treatment etc. would benefit or alleviate the condition of the person i.e. b(ii), and have formed a view on that, again either explicitly or by necessary implication.

61. Insofar as the use of language requiring inferences to be drawn, and/or shorthand, is concerned, this is permissible within limits. As O'Donnell J. provides at paras.42 and 43 of B.G:

"It may be the case that when the admission order under question is considered, particularly in light of the recommendation, those identified matters can be understood by implication even if they are not set out in express terms...."

62. In G.B. McCarthy J. observed:

"While clearly the subsequent part of the forms that record the basis for the clinical judgment must be completed, I am not convinced that there is a need for an extensive discussion. This is because the legislation does not require the forms to be furnished to the patient himself or herself, but instead to, among others, the Commission, Tribunal, Independent Psychiatrist and specially trained legal representatives. Hence some element of brevity or medical shorthand could be permissible, so long as it is capable of being understood by the persons who will have to consider the forms as part of the overall process."

63. However, that case demonstrates that inferences are only permissible up to a certain point. The person had been detained pursuant to s. 12(1), which provides that where a member of the Garda Síochána has reasonable grounds for believing that a person is suffering from a mental disorder and that because of the mental disorder there is a serious likelihood of the person causing immediate and serious harm, the member may, inter alia, take the person into custody. Where a person is taken into custody under subsection 1, he or she or any other member of the Garda Síochána shall make an application for a recommendation. There was no space on the relevant form for the applicant for the recommendation that the Garda had formed the necessary opinion as to the mental disorder and likely harm and the applicant had challenged the detention on the basis there was no evidence that the opinion had been formed. The tribunal affirmed the admission order and it was sought to judicially review the decision of the tribunal. The challenge was rejected by the High Court and that decision was appealed to the Court of Appeal. At para. 29 of his judgment, McCarthy J observed as follows:

"The evidence that that opinion has been formed does not have to be recorded in any particular way and can be established informally by - for example - a signed statement by the Garda in question or a record to that effect on the relevant forms. Nonetheless, compliance with the relevant provision involves a tribunal in addressing whether or not the necessary opinion was actually so held by the officer concerned on objective grounds. It might in theory be possible to draw an inference from facts of which a tribunal was satisfied to the effect that a particular opinion has been formed even though not stated but in my view on any analysis of the material a conclusion that the relevant opinion existed is untenable; as characterised by counsel for the applicant at the hearing it was a "leap too far" (if indeed a "leap" would ever be lawful). As can be seen from Forms 5 and 6 provision is made therein for doctors to state their opinions; there is no reason why such opinion could not be stated similarly in, say, an amended Form 3 or the Garda asked to make a brief statement in a proper case."

64. The conclusion that inferences may be permissible is consistent with F.C. v. Mental Health Tribunal [2022] IECA 290, a case about the adequacy of reasons given by a mental health tribunal, despite the rejection of the use of inference in that case. There, Ni Raifeartaigh J. observed that where the person the subject of the order gives evidence before the tribunal, it is necessary that the decision maker engages with their evidence and explains why it has not been accepted if that is the case. She noted that leaving inferences to be drawn is not sufficient. That observation was made where the person had argued he would take his medication in the community if released and that submission had not featured at all in the decision of the tribunal. Nonetheless, it was argued that it could be inferred that this evidence had been considered but not accepted. It is agreed by all that the obligation of a tribunal to give reasons for its decision cannot be "read across" to the instant context; but even leaving that aside, the nature of the inference argued for was so unconvincing that it is difficult to read the judgment as establishing an immutable principle rejecting the role of inference in all circumstances.

65. Context is all when one is considering inference or shorthand. I agree that language that does not explicitly address the statutory criteria, but when read in context implies a consideration of the statutory criteria, may be treated as sufficient grounds for the opinion. Equally, it may be possible to infer from the language used that the statutory criteria have been considered. Nonetheless there are limits to the use of implication and/or inference. For the reasons explained below, I consider those limits were exceeded in this case.

Application of principles to the instant case

66. I turn now to consider whether the Form 6 at issue in this case was completed in accordance with the instructions as specified by the Commission. At Box 7, the box identifying that the basis for admission was s.3(1)(b)(i) and (ii) was ticked. In other words, Ms. A was detained not on the harm ground but on the treatment ground.

67. The following wording appeared in Box 8: "Grandiose and paranoid, delusional beliefs, lacks insight into need for treatment". I am prepared to accept that this constituted sufficient grounds for the psychiatrist's conclusion that Ms. A had a mental illness, since the reference to grandiose and paranoid, delusional beliefs, may be treated as a signifier of a mental illness. Counsel for Ms. A argued that the reference, for example, to "paranoid" might apply to persons not suffering from a mental illness. If there was only a reference to "paranoid", that would likely be insufficient to indicate that Dr. Q had directed her mind to whether Ms. A was suffering from a mental illness within the meaning of the definition in the 2001 Act. But those three terms, taken together, are sufficient to explain why she concluded Ms. A had a mental illness. This is particularly so given what O'Donnell J. says in B.G. in relation to the recipients of Form 6, i.e. that they are likely, for the most part, to be persons with medical expertise who will understand the shorthand that is being used.

68. Turning to the grounds for the opinion that Ms. A required to be detained on the treatment ground, the reference to "lacks insight into need for treatment" may be interpreted as signifying that the psychiatrist had formed the opinion that the lack of insight would prevent the provision of treatment in the community and that therefore the second part of b(i) is met i.e. failure to admit to the approved centre would prevent the administration of appropriate treatment. It would have been desirable to elaborate further on this: the comment is extremely terse but nonetheless just about provides a sufficient ground.

69. However, there is no material at all identifying the grounds for Dr. Q's opinion that b(ii) was met i.e. that the reception, detention and treatment of Ms. A in the approved centre would be likely to benefit or alleviate her condition to a material extent. That is an important and discrete aspect of the test. Take, for example, a person with a longstanding treatment resistant mental illness where failure to admit them to the approved centre would prevent the administration of appropriate treatment that could be given only by admission, for example the trial of new medication. A psychiatrist may not necessarily be satisfied that reception, detention and treatment would likely benefit or alleviate the condition of that person materially given their previous history of unsuccessful hospitalisation, despite the fact that they met (b)(i).

70. By including b(ii), the legislature obviously wanted to ensure that persons could only be admitted on an involuntary basis, with all that entails for the liberty of the person, where it is likely to materially improve their situation. In other words, this is an important part of the definition that cannot be ignored. The psychiatrist must direct their mind to that question. He or she must identify grounds for their opinion that this part of the definition is met, however tersely or in summary fashion. Here, it is difficult to see how one can imply into "lacks insight into need for treatment" the basis for an opinion that admission would benefit or alleviate the condition of the person materially.

71. As counsel for the approved centre observed, nobody has queried the validity or genuineness of Dr. Q's belief that Ms. A met the criteria in s. 14. She had ticked the relevant box in Box 7 indicating that she believed s.3(1)(b)(i) and (ii) were satisfied. By ticking particular boxes under Box 7, the consultant psychiatrist must be taken to be addressing their mind to the statutory criteria and indicating their conclusion in that respect. But Form 6 also requires that the grounds for that opinion be set out and that means that every ground relevant to every part of that opinion must be set out, either expressly or inferentially.

72. As per the observations of McCarthy J. in G.B, there must be flexibility in considering whether the necessary opinion has been held and inferences may be drawn. It is important that psychiatrists are not placed under an overly onerous duty, or that overly prescriptive requirements are identified. There is no obligation to write a detailed report. Rather, the psychiatrist must do exactly what is said above Box 8: set out the grounds for their opinion that the person continues to suffer from a mental disorder. Because the definition of mental disorder has a number of components, the grounds for their opinion in respect of each component must be identified. The grounds need not make explicit reference to the statutory definition. I have explained above that it is sufficient if the informed reader can imply from the grounds that each aspect of the statutory definition has been considered. It must be remembered that often patients that are being admitted pursuant to s. 14 are quite unwell. There may be some urgency to their admission. On the other hand, prior to Form 6 being completed, there is an entitlement to detain them for up to 24 hours for an examination by the consultant psychiatrist, thus allowing time for the psychiatrist to arrive at their opinion and set out their grounds for same. Moreover, it may be recalled that a person may be detained for up to 21 days under an admission order and therefore the completion of Form 6 in accordance with its terms is a matter of considerable seriousness.

73. Having regard to those considerations, and allowing for inference, in this case there was a simple failure to address at all the matters in s.3(1)(b)(ii) of the definition of mental disorder. As a result, the psychiatrist did not fill in Box 8 as required by the terms of Form 6 as she failed to identify the ground upon which she considered b(ii) was met. Consequently, the admission order was invalidated and did not provide a basis to detain Ms. A. I therefore uphold the decision of the trial judge.

Current wording of Form 6

74. It has been brought to the Court's attention that in fact the Commission revised the side note to Box 8 following the judgment of Simons J. It now requires simply a "description of the mental disorder" i.e. omitting the word "clinical". A subsequent amendment to the form does not of course affect the interpretation exercise that the court must carry out on this appeal. The only way it might be relevant is in the context of an argument that the use of the word "clinical" might be interpreted to mean that the consultant psychiatrist does not have to make reference to the grounds for their view under s.3(1)(b)(i) and (ii) and a clinical description of the illness is sufficient (although that argument was not in fact made). I do not think any such argument could be correct. This is because the question of the consequences of the failure to admit, and the impact of the reception etc. in the approved centre are clinical matters, as is the consideration of whether admission would benefit or alleviate the condition. All the matters included in the definition of mental disorder have some clinical elements. Therefore, the reference to a "clinical description" in fact encompasses all of the matters that a psychiatrist must direct their mind to under s. 14.

Relevance of the recommendation

75. In the context of the hearing, legal submissions were made as to the role of the prior recommendation under s. 10 in deciding whether sufficient grounds have been provided in Box 8. It was suggested by counsel for Ms. A– and indeed by O'Donnell J. in B.G. - that where the general practitioner has directed his or her mind as to whether the person is suffering from a mental disorder, and where what the psychiatrist has to do in an admission order is to consider whether the patient continues to suffer from a mental disorder, one can look to the recommendation in order to supplement or to understand the observations of the psychiatrist in an admission order. In the instant case, this does not arise since there is nothing in the recommendation that is directed towards the omission that I have identified above, i.e. the lack of any reference to b(ii). The description given in Form 5, i.e. "presented with irrational and paranoid thoughts evidence of psychosis on a background of schizoaffective disorder" is relevant to the question of whether or not there is a mental illness, but it does not address itself to the consequences of admitting or not admitting the person and could not therefore be of assistance in this case. In my view, it is preferable to leave the question of what role the wording used in a recommendation may play to a case where it actually arises.

Purpose of Form 6

76. There was a sustained consideration of the use to which Form 6 is put, and the persons who may or may not rely upon it, from both parties to support their respective arguments as to the extent of the obligations of the consultant psychiatrist when filling it out. Although that is undoubtedly part of the general context, there is such a clear obligation to fill in Form 6 as specified by the Commission, and such an obvious breach of same in the instant case, that I did not consider it necessary to resolve those competing arguments on the use of Form 6 to arrive at my conclusion. Nonetheless, because this was the subject of extended submissions, I make the following observations.

77. Form 6 is sent to the Commission. That prompts the Commission to appoint an independent consultant psychiatrist from a panel that has been established. Under s.17(2)(a) the psychiatrist must examine the records relating to the patient. Those records are not defined but one can safely assume that they will include the admission order i.e. Form 6. Indeed, the admission order, and whether it has been completed correctly, is an issue that often arises before a tribunal. Similarly, many applications for judicial review in respect of a tribunal decision will often centre on whether the tribunal acted lawfully in upholding the validity of an admission order. Equally, decisions on applications under Article 40.4 in respect of detention authorised by an admission order, such as in the present case, will often be concerned with the validity of the admission order.

78. It was argued on behalf of the approved centre that the tribunal does not have the function of considering whether a patient had a mental disorder at the date of making the admission order, but only whether a mental disorder exists at the date of the tribunal hearing and therefore the reasons for the making of the admission order at the time of its making are not necessary for the exercise by the tribunal or Circuit Court of their respective functions (see para.102 of the written legal submissions). I do not consider that to be an accurate summation of the tribunal's functions. Section18(1) is in the following terms:

"18.—(1) Where an admission order or a renewal order has been referred to a tribunal under section 17, the tribunal shall review the detention of the patient concerned and shall either—

(a) if satisfied that the patient is suffering from a mental disorder, and

(i) that the provisions of sections 9, 10, 12, 14, 15 and 16, where applicable, have been complied with, or

(ii) if there has been a failure to comply with any such provision, that the failure does not affect the substance of the order and does not cause an injustice,

affirm the order, or

(b) if not so satisfied, revoke the order and direct that the patient be discharged from the approved centre concerned."

79. Thus, a tribunal has two quite distinct obligations: first, it must carry out what I will describe as a present-day analysis i.e. considering whether, at the time of the tribunal hearing, the patient is suffering from a mental disorder. That is a substantive evaluation informed by the psychiatric evidence before it. Second, under s.18(1)(a)(i), it must consider whether the provisions of sections 9, 10, 12, 14, 15 and 16, where applicable, have been complied with. This necessitates a consideration of whether the requirements of those sections were complied with at the appropriate time. In relation to s.14, that is when the admission order was made. Part of that compliance review is to ensure that the consultant psychiatrist observed the requirements of s.3(1) in concluding the person had a mental disorder.

80. This does not, contrary to the submissions of counsel for the approved centre, involve a substantive clinical review by the tribunal. That is reserved to the present-day analysis. Similarly, on an Article 40 inquiry, the High Court is not reviewing the medical merits of a decision. I fully accept that in such a context, the High Court cannot step into the clinical arena, for example by second guessing or disputing the substantive clinical opinion of the psychiatrist - see Hogan J. in Court of Appeal in A.B. v Clinical Director of St Loman's Hospital [2018] 3 I.R. 710, where he observed as follows:

"The High Court can direct the release of an involuntary patient by way of an Article 40.4.2 application not only where the order in question was good on its face, but also where there has been a fundamental breach of constitutional rights or the existence of some other material defect in the process ... No matter how brightly the beacon of liberty has heretofore shined to vindicate the constitutional rights of Article 40.4.2 applicants, an adjudication upon the purely medical merits of the detention of an involuntary patient under the 2001 Act seems to lie just outside the arc of that spotlight of review."

81. But the hands-off approach of the High Court to the substantive clinical evaluation (and indeed the tribunal in relation to whether the person had a mental disorder at the time of the making of the admission order, as opposed to when the person appears before the tribunal) does not mean that there is a similar hands-off approach to compliance with the procedural requirements of s.14. The tribunal must review whether the psychiatrist has complied with their obligation to be satisfied that the person detained has a mental disorder. So, for example, if a tribunal received an admission order where Box 8 was entirely empty, or included manifestly irrelevant material, a tribunal would in my view have obvious concerns about whether s.14 had been complied with. Therefore, the contents of an admission order, including the grounds upon which the psychiatrist is of the opinion that the person meets the definition of mental disorder, are potentially important for the purpose of the tribunal carrying out its functions, as well as for the High Court in the context of Article 40.4 applications and applications for judicial review of a tribunal decision.

82. One of the findings of the trial judge was that reasons must be stated, inter alia, to allow the person who has been involuntarily detained to know the precise basis upon which their liberty has been taken away, and that this is essential to allow them to consider their legal options. In fact a detained person may or may not be provided with the completed forms. There is no entitlement to receive them under the Act. Rather, s.16 provides that a patient will receive notice in writing of the making of the admission order, and s.16(2) sets out in detail those matters that must be addressed in the patient notification form.

83. Given that s.16 sets out in some detail what a person is entitled to receive following the making of an admission order, and that does not include the admission order itself, I have some reservations as to whether it can be assumed there is an entitlement in all circumstances on a patient to receive an admission form to vindicate their rights to challenge the decision, as found by the trial judge. But given that this is not an issue that requires to be considered for the purpose of deciding this appeal, I think it is preferable that I do not express a view on this issue. What is clear is that the lawyers of a person who is detained under an admission order receive that order when preparing for the tribunal hearing, and the grounds upon which the admission order was made will undoubtedly form an important part of their review.

84. In short, there are various different constituencies who receive the admission order. They will make different uses of it depending on their respective interests. All of them have an interest in receiving an admission order that complies with the requirements of the Commission, and in particular sets out clearly the grounds upon which the psychiatrist came to the conclusion that the person has a mental disorder. But the obligation to complete Form 6 in a compliant fashion comes, not from the uses to which it will be put, but rather from the obligation to complete it in accordance with the requirements as specified by the Commission pursuant to s.14.

85. Counsel for Ms. A, in their written submissions, placed some emphasis on the obligation for any document authorising the detention of a person to show jurisdiction on its face and cited case law in different contexts in this respect, including the extradition context. I do not consider that case law to be particularly relevant here, given that there is a clear statutory obligation to make an admission order in the terms specified by the Commission, and where the format specifically requires the grounds for the making of the opinion to be identified. In other words, the regime established by the 2001 Act and the Commission already requires that the admission order demonstrates the basis for the forming of the view under s.14. There is therefore no need to have recourse to case law that requires orders to display jurisdiction on their face given that obligation has already been identified by the Commission in Form 6.

Application under Section 9

86. To resolve the separate question of whether Form 4, used for the application to detain Ms. A, was completed in a compliant fashion, it is necessary to first consider s.9. It provides in relevant part:

"9.—(1) Subject to subsection (4) and (6) ... where it is proposed to have a person ... involuntarily admitted to an approved centre, an application for a recommendation that the person be so admitted may be made to a registered medical practitioner by any of the following:

(a) the spouse or civil partner or a relative of the person,

(b) an authorised officer,

(c) a member of the Garda Síochána, or

(d) subject to the provisions of subsection (2), any other person.

...

(3) An application shall be made in a form specified by the Commission.

...

(5) Where an application is made under subsection (1)(d), the application shall contain a statement of the reasons why it is so made, of the connection of the applicant with the person to whom the application relates, and of the circumstances in which the application is made."

87. Section 9(5) is somewhat unusual. It only imposes a duty to give reasons where an application is made by "any other person" i.e. not one of the categories listed at (a) to (c). No equivalent section exists in respect of the giving of reasons where a recommendation or admission order is made. When considering what is required by s.9(5), it is important to recall that a person completing Form 4 will not necessarily have any medical qualifications and therefore cannot be expected to form a view as the existence of a medical condition. The person is only triggering the first stage in a process that may lead to involuntary admission i.e. is making an application for a recommendation to a registered medical practitioner. There has already been judicial consideration of the correct interpretation of s.9(5). In A.R., Phelan, J. observed, admittedly in an obiter comment, as follows:

"As noted in A.A. (para. 32) the statutory requirement for reasons under section 9(5), at that point of the statutory process, is triggered in circumstances where the application is being made other than by (a) the spouse or civil partner or a relative of the person, (b) an authorised officer, or (c) a member of the Garda Síochána, making it clear that the Legislature mandated that an additional layer of protection was to apply in such a contingency. It appears clear that a requirement to explain why a person, being an applicant other than a prescribed category of person, is making the application arises as a safeguard to ensure that only persons with an appropriate interest in the well-being or care or control of a person with a suspected mental disorder have the power to trigger a process under the 2001 Act."

88. Counsel for Ms. A argued that, properly interpreted, s.9(5) requires the applicant - in this case the nurse at the ER in Beaumont Hospital - to explain not only why they are making the application, but also why none of the persons identified in (a), (b) and (c) are making the application. He also contended that s.9(5) requires the person making the application to explain precisely why it is appropriate to make an application. He criticised the completed Form 4 in this case for an absence of information on both fronts.

89. Counsel for the approved centre argued that s.9(5) was only intended to address the mischief of inappropriate persons making applications. In other words, it is only necessary for a person making an application under s.9(1)(d) to explain the circumstances that prompted them to make the application, given that they do not fall into any of the categories set out in s.9(1)(a)-(c). He asserted that the completed Form 4 explained precisely why the applicant was making the application.

90. The interpretation advanced on behalf of Ms. A does not in my view reflect the language used in s.9(5). The application must contain a statement of the reasons why it is so made i.e. by any other person. This suggests not a requirement for a general statement of why it is made but rather why it is made by a person who does not fall into one of the categories set out at (a) to (c). It must set out the connection of the applicant with the person to whom the application relates. That obviously relates exclusively to the connection between the applicant and the person. Section 9(5) also requires that the circumstances in which the application is made be set out. That requirement, in my view, is linked to the same issue: the information provided will permit an objective analysis of whether the application is an appropriate one, despite the fact that the person bringing the application is neither a family member nor a person nominated to bring such applications under s.9.

91. As was pointed out at the hearing by counsel for the approved centre, the interpretation advanced by counsel for Ms. A would mean that a person making an application under (d) would be required to explain why a very large number of people were not making the application, despite the fact that the person making the application may not know the person the subject of the application at all, or have any knowledge of their family circumstances. This is amply demonstrated by the definition of "relative" in s.2 of the 2001 Act i.e. "In relation to a person, means a parent, grandparent, brother, sister, uncle, aunt, niece, nephew or child of the person or of the spouse of the person whether of the whole blood, of the half blood or by affinity". Requiring a person making an application to explain why, for example, a relative was not making the application would clearly place an impossible burden on that person, particularly given that a person potentially in need of involuntary admission to an approved centre may be unwilling or unable to engage in discussion as to why an application has not been brought by relatives, or indeed authorised officers or members of AGS. Moreover, s.9, and indeed the whole scheme in respect of involuntary admissions, is designed to address urgent and pressing circumstances concerning the safeguarding of persons who are unwell and who may be in need of urgent assessment. The interpretation advanced by counsel for Ms. A would likely undermine the statutory aim.

92. In summary, I am satisfied that on a proper construction of s.9 (5), an applicant who falls within subsection (d) is required only to give reasons why he/ she is making the application; and not to explain or give reasons why persons who fall within the other categories of potential applicants referred to at subsections (a), (b) and (c) are not making the application. Any other construction would likely result in the imposition of an obligation which may be impossible to fulfil.

Application of principles

93. Here, I consider that there was sufficient information provided on Form 4 to make clear the identity of the applicant, why she was making the application and why it was appropriate for her to do so as opposed to any other person. The applicant gave as her full address the Emergency Department, Beaumont Hospital, Beaumont D9. Immediately, it was clear that she was making the application in the context of her work at the Emergency Department. She did not identify herself as a nurse or explain what her role was in the Emergency Department. However, she made it clear that she was working in same. The side note to Box 8 read: "State reason for making an application" and Box 8 was headed up as follows: "I am applying for a recommendation for the involuntary admission of the above-named person because;" she wrote the following words "Husband brought patient into ED, bizarre behaviour, paranoid."

94. In respect of Box 9 where the side note says as follows: "Circumstances in which the application is made"; she wrote, "Observed to be paranoid and psychotic in the ED".

95. From that information, it was clear that Ms. A had been brought into the Emergency Department by her husband and that she was behaving in a bizarre way and displaying paranoia. She was also stated to be observed to be paranoid and psychotic in the Emergency Department. In those circumstances, it is not hard to understand why an application was made by the nurse, given that bizarre behaviour, paranoia and psychosis are known symptoms of mental illness. Moreover, it was clear that her husband was clearly concerned about her because he had brought her into the Emergency Department to seek treatment for her. It is true that the nurse did not explain she was making the application rather than her husband. But, as identified above, this is not what s.9(5) requires.