LORD HODGE: (with whom Lord Kitchin and Lord Sales agree)

1. This appeal concerns a conveyancing dispute. It is a dispute between the partners of a firm of advocates and notaries public, Atkinson Ferbrache Richardson (“AFR”), and their clients, Richard and Christine Lovering (“Mr and Mrs Lovering”) as to whether AFR were negligent in allowing their clients to purchase a residential property with a defective title. At the heart of the dispute is the question whether the title was defective. It is unfortunate that the case has involved a five-day trial before the Royal Court, a hearing in the Court of Appeal of Guernsey and an appeal as of right to the Board.

The facts

2. In 2008 Mr and Mrs Lovering engaged AFR to act for them in the purchase of a house known as La Roche Douvre in Torteval, Guernsey. The house is located close to the public road, Rue de la Folie, which runs on the northern boundary of the property but the house is at a height above that road which makes impracticable to have vehicular access to and from it. As a result, access to the house is by a driveway from the Rue de Rougeval which is located to the South-east of the house. By conveyance dated 13 January 2009 the owner of the house, Mrs Harrison, sold the property comprising the house and the driveway (“the Property”) to Mr and Mrs Lovering.

3. In 2012, Mr and Mrs Lovering encountered a difficulty when they attempted to sell the Property because the purchasers, Mr and Mrs Garrod, acting on legal advice, were not satisfied that they had a good title to the whole of the driveway from the public road to the house. This caused delay in the sale transaction while Mr and Mrs Lovering’s lawyers negotiated the purchase of a small piece of land, which the Board describes below, to rectify what they believed to be a defect in the title to the driveway to the house. Having purchased this ground, arranged for earthworks to remove a bank of earth and level the surface of the ground, Mr and Mrs Lovering had tarmacadam placed on the purchased ground to create an access route which runs entirely on the land which they had been advised was what they owned. Having done so and having thus satisfied Mr and Mrs Garrod as to the title, Mr and Mrs Lovering conveyed the Property to them on 31 January 2013.

4. Mr and Mrs Lovering commenced legal proceedings for damages for professional negligence against AFR in the Royal Court in 2015. In their claim against AFR Mr and Mrs Lovering claimed substantial consequential losses which the Royal Court, if it had found in their favour, would have disallowed as being too remote. Mr and Mrs Lovering did not appeal that part of the Royal Court’s judgment with the result that their claim is estimated at about £36,000 and interest. The question which arises in this appeal is whether there was a defect in title to the Property which gives the Mr and Mrs Lovering the legal basis to claim those damages.

5. In order to understand the dispute over title it is necessary to describe the access route as constructed and to set out the parts of the conveyances which are relevant to the question in dispute.

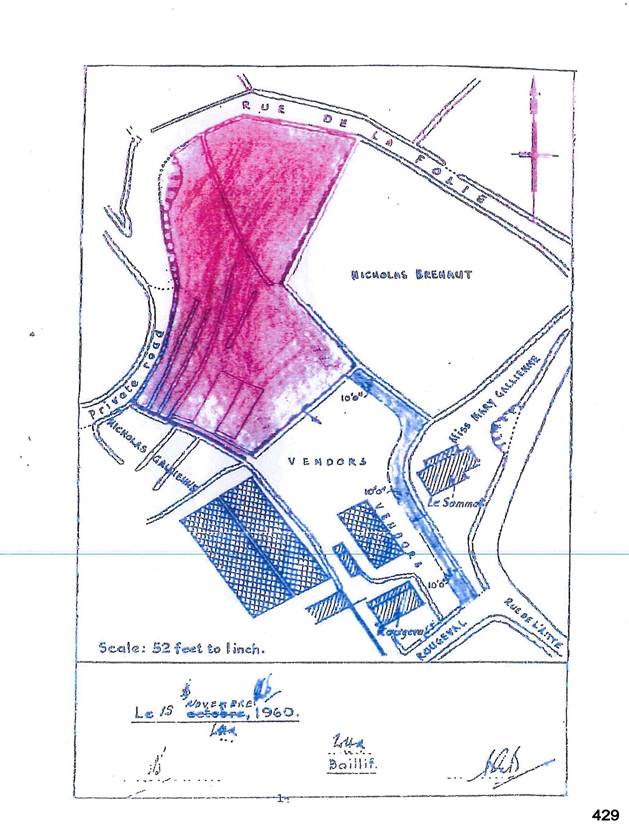

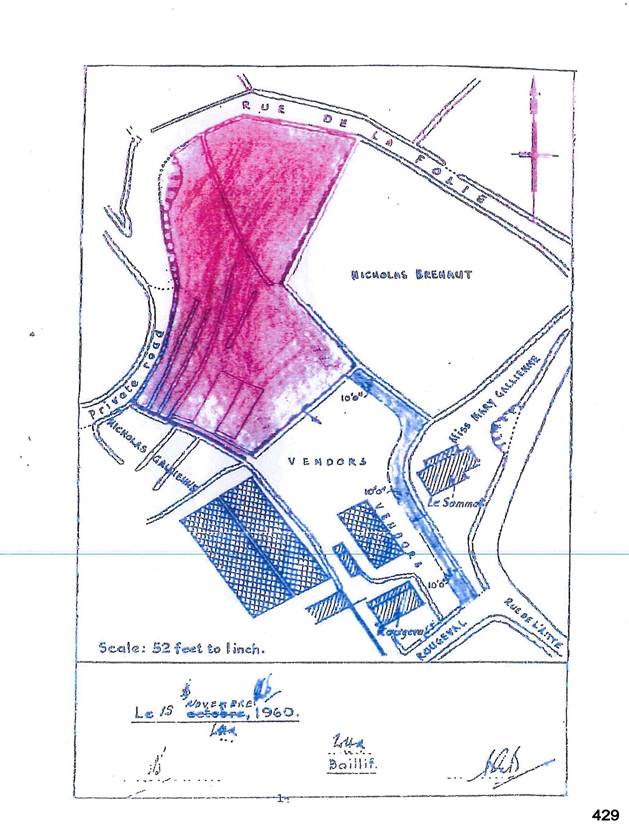

6. The driveway as originally constructed comes off the Rue de Rougeval in a North-westerly direction and runs in what is almost a straight line with only a very gentle curve to the North-west until it joins the plot of ground on which La Roche Douvre sits. On the North-eastern side of the driveway for about 40% of its length is the South-western boundary of the property known as “Le Sommet”, which used to be owned by Mr and Mrs Brookfield and is now owned by Mrs Clavadetscher. Continuing up the driveway as it was originally constructed one passes the junction of the South-western and the North-western boundaries of the “Le Sommet” land and the latter boundary curves away from the driveway for an unspecified distance in the range of 20 to 30 feet until it joins the South-western boundary of a small field (which has been called “the Brehaut field” in these proceedings) which runs in a straight line to a point beside which the driveway joins the plot of ground on which La Roche Douvre is built. As one progresses in a North-westerly direction up the driveway as originally constructed that driveway is separated from the South-western boundary of the Brehaut field by a small plot of ground of roughly triangular shape but, about half way up that boundary of the Brehaut field, the Eastern edge of the access track joins and runs along that boundary until the access track reaches the plot on which La Roche Douvre is built. There is attached to this advice a plan, numbered 2842, on which one sees among others the Le Sommet land and the Brehaut field.

7. Mr and Mrs Lovering, acting on legal advice, claim that the driveway as originally constructed did not run along the course which was stated in their title to the property and shown on the attached plan 2842 and that in part it ran over ground belonging to a third party. Further, because of the conveyance in 1984 by Mrs Harrison, their predecessor in title, of ground which was shown in their title plan to be part of the intended driveway to their house, lying between the driveway as constructed and the South-western boundary of the Brehaut field, they claim that, when they purchased the Property in 2009, it was no longer possible for the driveway in its entirety to run wholly within the land conveyed to them. As a result, their legal means of access to their property had been materially restricted.

The title to La Roche Douvre

8. The house now known as “La Roche Douvre” was originally called “La Folie”. A separate property (comprising that house and the driveway) was created out of land owned by Mr and Mrs Le Lacheur and was located on the North-east of the larger area of land which they owned which extended South to border the Rue de Rougeval.

9. Mr and Mrs Le Lacheur by a conveyance dated 15 November 1960 (“the 1960 Conveyance”) conveyed that separate property to Mr and Mrs John de la Mare. The property was described as consisting of two parts both of which were shown on the plan 2842 annexed to the conveyance, the first part being the substantial piece of ground within which the house is located and the second part being the driveway. As the Board discusses in more detail below, the driveway was described as “a strip of ground coloured in blue with measurements on the said plan” and its Western boundary was described as land retained by the sellers, Mr and Mrs Le Lacheur, with markers between them (“des bornes entre deux”). In the verbal description the Eastern boundary of the driveway was described in substance as the Brehaut field and the Le Sommet land with hedges between. The plan 2842 is at a scale at 52 feet to the inch and shows the first part in red and the driveway in blue with three measurements of the width of the driveway of precisely ten feet (10’0”).

10. Mr and Mrs de la Mare sold that property in 1967 to Mr and Mrs Humphrey-Lewis. Nothing turns on the terms of that conveyance. In 1968, when Mr and Mrs Humphrey-Lewis sold the house and driveway, they retained from the property initially created by the break-away conveyance of 1960 a substantial plot of land on the Western side of the first part on which the house was located (the first part being shown in red on plan 2842). This reduction in the size of the grounds of the house is not relevant to the dispute which has arisen. The conveyance dated 17 September 1968 (“the 1968 Conveyance”) transferred the property, thus reduced in size, to Miss Una Kaines, who on marriage became Mrs Harrison. The 1968 conveyance described the driveway as a strip of ground about ten feet in width indicated in blue on the annexed plan (plan 4782). The plan showed the driveway coloured in blue on the same location and with the same measurements as those in plan 2842 annexed to the 1960 Conveyance. The 1968 Conveyance described the boundaries of the driveway in similar terms to those in the 1960 Conveyance. In particular, the conveyance described the Western boundary of the driveway as land belonging to the widow of Mr Le Lacheur “des bornes entre deux”.

11. By a conveyance dated 17 May 1984 (“the 1984 Conveyance”) Mrs Harrison conveyed to Mr and Mrs Brookfield a triangular area of land “forming part of the driveway shown coloured blue on Plans Nos 2842 and 4782”. This was ground lying between the driveway as constructed and the junction of the North-western boundary of the Le Sommet land and the South-western boundary of the Brehaut field respectively. Mr and Mrs Lovering claim that the selling off of this plot of land materially restricted their right of access to their house.

12. In 2009 Mrs Harrison sold the Property (ie the property conveyed by the 1968 conveyance minus the plot of ground sold in the 1984 Conveyance) to Mr and Mrs Lovering by a conveyance dated 13 January 2009 (“the 2009 Conveyance”). In this conveyance it was stated that unless the context otherwise requires:

“1.1 ‘the Driveway’ means the driveway measuring ten feet or thereabouts in width, shown coloured blue on plan 4782, and is the driveway referred to in item 1.6.2 below;”

Item 1.6 described the property as (1) the dwelling house and garden and (2) the driveway. Clause 5 of the conveyance provides:

“That part of the Property described in Item 1.6.2 hereof is bounded on or towards the:

5.1 North-east by the field belonging to the Brehaut Heirs, an earth bank (fossé) forms the boundary;

5.2 South-east for a short distance and the North-east by land with a dwellinghouse known as ‘Le Sommet’ belonging to Mrs Clavadetscher, the hedge (fossé) forms the boundary and belongs to the Property (as set out in the 1984 Conveyance);

5.3 South-east by Rue de Rougeval;

5.4 South-west, the West, the North-west and the South-west by land with a dwellinghouse known as ‘Rougeval’ (otherwise known as ‘Laitte Revel’) belonging to Mr and Mrs Harding, boundary marks between; and

5.5 North-west by the continuation of the Driveway as referred to in Item 1.6.1 above.”

13. It is clear from those titles and the parties do not dispute (a) that the driveway which was conveyed to Mr and Mrs Lovering in 2009 is the same driveway as was conveyed in the 1960 Conveyance which is the root title, subject to the subtraction of the land conveyed by the 1984 Conveyance, (b) that, so far as relevant, plan 2842 annexed to the 1960 Conveyance is identical to plan 4782 annexed to the 1968 Conveyance which is the plan referred to in the 2009 Conveyance to Mr and Mrs Lovering, and (c) that the verbal description of the Western boundary of the driveway which was conveyed in 1960 does not materially differ in the 1960, 1968 and 2009 Conveyances: each describe the existence of the boundary markers. But it was not disputed by Advocate Ferbrache and Advocate Barnes that the boundary markers, if they were placed on the ground in 1960, would probably have been granite setts which had not remained in situ and that the references in the later conveyances to “bornes” or boundary markers were a practice of conveyancers to make sure that the description which they used in drafting a conveyance tallied with the prior titles rather than a description of what was visible on the ground at the date of the relevant conveyance. The Board also notes that the description of the boundary of the driveway in para 5.4 of the 2009 Conveyance (above) is consistent with the existence of the right-angled bend which one can see in the plan 2842 at the location which has given rise to this dispute.

The judgments of the Guernsey Courts

14. The claim was tried by the Deputy Bailiff and Jurats. In a careful judgment handed down on 28 November 2017 the Royal Court dismissed the claim. Critical to the findings of the Royal Court was the conclusion of the Deputy Bailiff in para 81 of the judgment, after considering the cases, which the Board discusses below, of Payne v Walsh (unreported, 30 October 1986), a decision of the Guernsey Court of Appeal, and two English cases, Wigginton & Milner Ltd v Winster Engineering Ltd [1978] 1 WLR 1462 and Willson v Greene [1971] 1 WLR 635. The Deputy Bailiff found (para 80) that the default position in conveyancing was that “unless and until there is something explicit incorporating something found on the plan into the verbal description, any plan referred to is to assist in identifying the subject matter of the conveyance”. The Deputy Bailiff’s conclusion (para 81) was that the proper construction of each of the relevant conveyances is “that the boundary with Laitte Revel, owned by Mr and Mrs Le Lacheur was fixed by reference to the physical characteristics of where the boundary marks were located and not solely by measurement as shown on the annexed plan.”

15. As a result of that conclusion, the question was seen as a question of fact: where were the boundary markers placed on the ground in 1960? To answer this question the Jurats had regard to, among others, an Ordnance Survey map of the land from 1963 which showed the driveway as constructed running in almost a straight line, as the Board has said, which as the Deputy Bailiff recorded (para 85) did not “hug the boundaries with Le Sommet and the field owned by Mr Brehaut as shown on plan 2842”. The Jurats also had regard to aerial photographs and inferred that the driveway as constructed had remained in the same position since its initial construction shortly after the 1960 Conveyance and had followed a pre-existing track. They also accepted Mrs Harrison’s evidence that the route of the driveway as constructed had not altered since she purchased La Roche Douvre in 1968. The Jurats also saw photographs of the driveway as constructed before Mr and Mrs Lovering repurchased and levelled the land, which Mrs Harrison had sold off in the 1984 Conveyance, which showed a hedge separating the land sold in the 1984 Conveyance from the driveway as constructed. The Jurats also visited the site on a vue de justice to determine where, on a balance of probabilities, the boundary markers would have been placed in 1960. They inferred from the topography of the ground of the driveway and neighbouring land and other evidence that the land sold in the 1984 Conveyance would have been at a higher level than the driveway and that it would have involved significant earthworks to create the driveway on the strip of ground shown on plan 2842.

16. The conclusion that significant earthworks would have been required is not disputed in this appeal as it is accepted that the land sold in 1984 comprised a bank of ground of between four and five feet in height above the driveway as constructed. Nor is it contested that there was a hedge, which had been planted since 1960, on the boundary between that land and the driveway as constructed. Mrs Harrison’s undisputed evidence, which the Jurats accepted, was that she sold off that ground because she had no access to it, there being a 15-year old hedge separating it from the driveway as constructed. The Board was also shown a plan registered in the Cadastre in accordance with article 9 of the Cadastre Law 1947 by Carey Langlois, advocates, in the context of the 1984 Conveyance, which showed the roughly triangular (in fact quadrilateral) piece of ground sold by Mrs Harrison lying against the North-east edge of the almost straight driveway as constructed.

17. The Jurats, as the masters of the facts, concluded that the driveway as constructed would have followed the alignment marked out by boundary marks in 1960, following the natural contours of the land and, having regard to the topography, as close as possible to the Brehaut field. The Jurats held that the boundary marks would not have been laid out in accordance with the boundaries shown on plan 2842 and concluded that Mr and Mrs Lovering had failed to prove their case that the land on which La Roche Douvre was built was enclavé.

18. The Board observes that Mr and Mrs Lovering’s case was not that their ground was enclavé but that vehicular access to their home was materially compromised by the sale of land in the 1984 Conveyance. But that makes no real difference because, if the correct legal and factual conclusions were, as the Royal Court found, that the South-western boundary of the strip of ground conveyed in the 1960 Conveyance and in the subsequent conveyances matched the South-western edge of the driveway as constructed, Mr and Mrs Lovering would have acquired title to a ten foot wide driveway in 2009.

19. The Court of Appeal in a judgment dated 22 June 2018 issued by its President, the late Robert Logan Martin QC, reversed the order of the Royal Court. In its careful and detailed judgment the Court of Appeal analysed Payne v Walsh and the cases to which it referred as the Deputy Bailiff had done. The Court of Appeal summarised its understanding of the law at para 86:

“From a consideration of these authorities, and in particular Payne v Walsh which is a decision of this Court, we identify the following approach. In identifying what are the boundaries of land which is the subject of a conveyance, it will always be permissible to look at any annexed plan, even if the plan is stated in the conveyance as being for identification but not of limitation. In that situation, the words of description will rule in the event of a discrepancy between the words and the plan. That is the effect of what was said by Buckley and Bridge LJJ in Wigginton & Milner Ltd. In a situation where an element of the plan is referred to directly in the words of description, such as the reference to the line of demarcation in Payne, the plan will be regarded as having ‘been brought in as a part of the specific description of the property without qualification and that forms the equivalent of a verbal description’ to quote Collins JA. That will be the case even where the plan is referred to otherwise as being by way of identification but not of limitation. That is the consequence both of what was the result in Payne v Walsh and of what was said by Romer LJ in Webb v Nightingale.”

20. The Court of Appeal examined each of the conveyances of the relevant ground since 1960 and applied that analysis to their terms. Because, as will appear from the discussion below, the Board has concluded that the Court of Appeal was essentially correct in its reasoning and its application of the law to the relevant conveyances, it is not necessary to set out that reasoning in any detail. In short, the Court concluded that the driveway conveyed in the 1960 Conveyance was the land shown coloured blue on the plan 2842 (para 88). So far as relevant, the 1968 Conveyance conveyed the same land (para 103). The Court of Appeal then analysed the 1984 Conveyance and concluded that the ground conveyed thereby “occupied a material part of the width of the driveway at the location of the right-angled bend” (para 113).

21. The Court of Appeal held on an analysis of those conveyances that Mr and Mrs Lovering had established their claim (in para 5(c) of the Cause) that “it was therefore no longer possible at the time of the Purchase [ie the 2009 Conveyance] for the Driveway in its entirety to run along the Intended Course or otherwise to run over land which formed part of the Property” (para 114).

22. As there was no dispute that in 2009 Mrs Harrison did not own and could not convey the land transferred to Mr and Mrs Brookfield by the 1984 Conveyance, an analysis of the terms of the 2009 Conveyance by which Mr and Mrs Lovering acquired their title was not strictly necessary. The Court nonetheless analysed the 2009 Conveyance, drawing attention to the irregular boundary with the Laitte Revel land on the West in clause 5.4 of the 2009 Conveyance, which the Board has set out in para 12 above which was consistent with the dog-leg shape of the strip of ground, including the right-angled bend, shown on the plans 2842 and 4782. The Court also concluded that the 2009 Conveyance excluded from its scope the plot of land conveyed by the 1984 Conveyance (para 138). As the conclusion that the land of the 1984 Conveyance was (correctly) excluded from the 2009 Conveyance is not challenged in this appeal, the Board needs to say no more about it other than that it agrees.

The appeal

23. AFR appeal to the Board with the permission of the Court of Appeal. In a lengthy and inappropriately argumentative Statement of Facts and Issues, which was principally the work of the appellants and appears not to have been agreed, AFR raise numerous issues for determination. But there are in reality only two issues. They are, first, whether the Court of Appeal erred in its construction of the 1960 Conveyance and in its application of the law relating to the role of annexed plans to that conveyance, and, secondly, if it did not err in that respect, whether the Court of Appeal was correct to find that there was a defect in title in the 2009 Conveyance because a material part of the driveway had been conveyed away by the 1984 Conveyance.

Discussion

24. The central issue on this appeal is the correct interpretation of the 1960 Conveyance, and in particular whether it shows an intention that the title to the driveway should follow the line of the strip of ground shown on the annexed plan 2842. The consequent question is whether the sale of the land in the 1984 Conveyance materially reduced the access route to which Mr and Mrs Lovering had title.

25. If the Court of Appeal were wrong in its construction of the 1960 Conveyance and the Royal Court were correct that that conveyance required the advisers of subsequent purchasers to ascertain where the temporary boundary markers had been placed in 1960 in order to determine whether their clients had obtained a good title to the driveway, no criticism is made of the approach of the Jurats, which was based on the extensive material presented to them, that the driveway had since 1960 been located in the same position. Nor, in that event, do Mr and Mrs Lovering challenge the conclusion that, on a balance of probabilities, the parties would have taken into account that there was elevated ground next to the junction of the Le Sommet land and the Brehaut field which would have involved considerable earthworks to create an access route, when placing boundary markers for the South western boundary of the driveway in 1960. While there might have been an alternative view of the facts, supported by the plan 2842 with its dog-leg configuration of the strip of ground and the sharp right-angled bend, that the sellers wished the strip of land in the break-away conveyance to cling to the North-western boundaries of their property, notwithstanding the necessity for earthworks, that is not now in issue as a question of fact. But the question is whether the 1960 Conveyance allowed the parties to extend the South-western boundary of the driveway beyond the boundaries shown in the plan 2842.

26. The Board bears in mind that the purpose of a conveyance of land is to create a clear title to land on which a subsequent purchaser, purchasing, as in this case, many years after the initial title was created and having no knowledge of the circumstances at the time of the initial title, can place reliance. Certainty is an ideal but it is often not achievable, particularly in a break-away conveyance of rural property where there are no distinguishing features on the land, such as a river or a wall, which can operate as reasonably permanent boundaries by which to describe the property conveyed. Annexing a plan to a conveyance can therefore be a very useful means of preserving a long term record of the boundaries of the property conveyed.

27. The parties agreed that it is the general practice of conveyancers in Guernsey when preparing a conveyance for their clients to study the title to the property and visit the site to understand the description of the boundaries on the ground. That is readily understandable. Where permanent features are recorded in a title and can be identified on the ground it is a straightforward exercise for a skilled conveyancer to satisfy himself or herself as to the application of the title on the ground and thus identify what was conveyed. Identification in a title by impermanent boundary markers, which one would expect to be absent years later, and requiring the conveyancer in future to infer from the topography where the markers might have been is a much less satisfactory exercise. Sometimes that exercise may not be avoided, for example where the property of A is said to be bounded on one side by the property of B and the property of B is said to be bounded on the same side by property of A and no further description is given. But where a plan is annexed to the conveyance, it may often be possible to avoid that complication.

28. In Guernsey, the leading authority on the use of plans in conveyances is Payne v Walsh (above). In that case the conveyance stated that the premises conveyed were shown coloured pink on an annexed plan “by way of identification but not of limitation” but, in the verbal description of the boundaries the premises were described as bounded “on or towards the North by a cartway (shown coloured green on the said plan) …”. Unsurprisingly, the Court of Appeal in its judgment delivered by Collins JA concluded that the plan had been brought in as a part of the specific description of the property without qualification, that it formed the equivalent to the verbal description and was incorporated into the verbal description.

29. The Court of Appeal of Guernsey in that case drew on the English case of Wigginton & Milner Ltd (above) in ascertaining the correct approach to the relationship between a verbal description of a boundary and what was shown on an annexed plan. In that case the delineation of the subjects of sale on the plan annexed to the conveyance was stated to be “by way of identification only”. That notwithstanding, the Court of Appeal of England and Wales held that the plan could be considered to resolve problems left undecided by the explicit descriptions of the parcels. Where there was no conflict between the plan so described and the explicit verbal descriptions of the parcels, the plan could be used to identify the boundary which was otherwise unclear. In the leading judgment (p 1470) Buckley LJ cited with approval Romer LJ’s explanation of the words “for the purpose of identification only” in the unreported case of Webb v Nightingale (which is cited by Foster J in Willson v Greene [1971] 1 WLR 635, 639). Romer LJ stated:

“Words of that kind are, of course, frequently used in conveyances in which parcels are described in the body of the deed. In such cases the plan is merely to assist identification, and, in the event of any inconsistency arising, is subordinate to the verbal description.”

Such words are not seen in the 1960 Conveyance which is the focus of this appeal. Of more relevance and significance is the statement of principle by Buckley LJ (p 1473G-H) where he said:

“When a court is required to decide what property passed under a particular conveyance, it must have regard to the conveyance as a whole, including any plan which forms part of it. It is from the conveyance as a whole that the intention must be ascertained.”

He went on to state that the court must give effect to any stipulation in the conveyance that one part of the conveyance shall prevail over another part of it in the event of a contradiction, but absent a contradiction the court could look at a plan which was described as being “for identification only” to assist in understanding the description of the parcels. In that case, as he stated (p 1474H) he was able to decide the boundaries of the parcel “looking only within the four corners of the conveyance” as there was sufficient information in the description of the parcel taken in conjunction with the plan. Bridge LJ agreed with Buckley LJ and added comments on the effect of the phrase “for the purpose of identification only”. He stated (p 1475):

“When a conveyance plan which is said to be for the purpose of identification only shows a boundary line which differs in detail from some physical feature on the ground which the conveyance otherwise indicates as the intended boundary line, it is clear that the latter prevails over the former.”

But as the Board has said, there is no such statement of precedence in the 1960 Conveyance.

30. While this case is to be decided on the basis of the Court of Appeal’s approach in Payne v Walsh and the English authorities to which the Court of Appeal had regard in that case, it is interesting to note that Scots law, whose land law like that of Guernsey has a strong civilian element, addresses these questions in a similar manner. When statements within a description are in conflict, it is a matter of construction of the conveyance to see which, if any, is meant to be the controlling one. In general, a verbal description may be regarded as prevailing over conflicting indications but a conveyance may subordinate the verbal description to the boundaries shown on a plan: William Gordon and Scott Wortley, Scottish Land Law, 3rd ed (2011), para 3.08. In George Gretton and Kenneth Reid, Conveyancing, 5th ed (2018) the learned authors point out that the statement in a conveyance of the status of a plan only matters if the discrepancy is an irreconcilable one. They state (para 12.22):

“If it is reconcilable then there is no difference: in every case the effort has to be made to read the verbal description and the plan as two views of a single truth.”

31. In this appeal Advocate Ferbrache and Advocate Barnes accepted as accurate the Court of Appeal’s summary of the correct approach in para 86 of its judgment which the Board has quoted in para 19 above. The Board does not disagree but considers that the correct approach would be more fully stated, setting the Court of Appeal’s summary in its proper context, if one were first to state the important principle which Buckley LJ articulated and which the Board has quoted (in para 29 above), that the court must have regard to the conveyance as a whole, including any plan which forms part of it: “It is from the conveyance as a whole that the intention must be ascertained”. This points to the sound common sense of the approach of Professors Gretton and Reid: that one should attempt to read the description and the plan as “two views of a single truth”.

32. The Board must now apply the law as so stated to the circumstances of this case.

33. The 1960 Conveyance, as the Board has said, described the property conveyed in two parts. The first part, which comprised the substantial area of ground on which the house was built as “(le dit morceau de terre teint en rouge sur le plan ci-annexé et paragraphé par nous soussignés Bailiff et Jurés)” and went on to describe its boundaries in general terms by reference to the neighbouring properties.

34. In accordance with conveyancing practice at that time the property conveyed was described by reference to the compass point which it occupied in relation to its neighbour, ie the property conveyed “lying to the east of” the neighbouring property (“gisant à l’Est de”). By the time of the 2009 Conveyance practice had changed, as the Board has shown (para 12 above), and the boundaries are described by the compass point at which the neighbouring land lies in relation to the conveyed property.

35. The land which the 1960 Conveyance conveyed for the access driveway was described as follows:

“SECUNDO: une lisière de terre (teint en bleu, avec mésurage, sur le dit plan) et aboutissant au Nord sur le morceau de terre du premier item de ce bail et au SUD sur la route de Rougeval, …; GISANT:- à l’EST ou environs des dits maison, serre et terrain appartenant aux dits Bailleurs, des bornes entre deux et à l’OUEST ou environ du dit courtil appartenant au dit Nicholas Brehaut et d’une maison appelée ‘Le Sommet’ avec serre et terrain appartenant à Demoiselle Mary Galliene, des fossés entre deux.” (Emphasis added)

36. It is of note that the conveyance (in the first phrase underlined above) does not describe the plan as indicative only. On the contrary the plan is stated to be “avec mésurage” which would be pointless if it were intended to be indicative only. The plan forms part of the description of the piece of ground. The plan itself is a scale plan at 52 feet to the inch and shows the measurement of the blue strip of ground as being ten feet in width. That measurement is shown in three places along the route of the intended driveway. The only place at which the driveway is shown on the plan to be slightly wider is at the right-angled bend to the west of the junction of the boundaries of the Le Sommet land and the Brehaut field. The inside edge of this bend where the driveway moves from a North-easterly direction to a North-westerly direction is softened into a more gentle curve to allow vehicles to traverse the sharp corner. But as the Court of Appeal correctly stated in para 89 of its judgment, does not extend the Western boundary to any material extent into the Laitte Revel land. It is also clear that throughout its length the strip of land which was to be the driveway hugs the boundary of the Le Sommet land and the Brehaut field. Further, and most significantly, on the face of the 1960 Conveyance and without extrinsic evidence there is no conflict between the plan and the description of the western boundaries by reference to boundary markers.

37. It is also significant that in the 1968 Conveyance the width of the strip of ground was stated not only on the plan but also in the verbal description itself: “une … lisière de terre de dix pieds ou environs de laize indiquée en teint bleu sur le dit plan ci-annexé”. The ten feet in width in both conveyances is part of the verbal description, by incorporation in 1960 and by direct expression in 1968.

38. The Board agrees with the Court of Appeal that the reference in the 1960 Conveyance to the scale plan “avec mésurage” incorporated the ten feet width of the strip of land into the description of the boundaries. Far from there being a contradiction within the conveyance itself, it required the extensive fact-finding exercise which was undertaken before the Royal Court in a five-day hearing to give rise to findings of fact as to the likely position of the boundary markers over 50 years previously in order to create a contradiction. In the Board’s view, there was and is no doubt as to the location of the boundaries of the strip of ground with the Le Sommet land and the Brehaut field and the width of the strip of ground conveyed must be taken from those boundaries. The location of the boundary marks in 1960 was dictated by the words of description, including the measurements shown on the plan. In the context of a break-away conveyance of rural land, the expedient of having a map to govern the boundaries makes good sense when the boundary markers would not be expected to be permanently on site. A description by reference solely to boundary markers which would in all likelihood disappear over time without some other guide as to their location is a recipe for disputation as this litigation shows.

39. It is to be expected that Mr and Mrs Le Lacheur would have wanted the driveway to lie as close as possible to the boundary of their land with their neighbours. It is indeed unfortunate that the conveyancer in 1960 may not have taken account of the unsuitability for inclusion in the proposed access route of the small parcel of the land beside the junction of the boundaries of the Le Sommet land and the Brehaut field because of its topography. Be that as it may, the Board is satisfied that the Court of Appeal was correct in its interpretation of the 1960 Conveyance, with the result that the South-western boundary of the conveyed strip of land at the disputed point lies materially to the East of the South-western boundary of the driveway as constructed.

40. The land which Mrs Harrison conveyed to Mr and Mrs Brookfield by the 1984 Conveyance at the junction of the Le Sommet land and the Brehaut field was described in the conveyance in these terms:

“A TRIANGULAR AREA OF LAND forming part of the driveway shown coloured blue on Plan Nos 2842 and 4782 …

THAT the area of land hereby conveyed is BOUNDED

On or towards the North-east for a distance of approximately thirty feet by a field owned by Miriam Robillard (née Brehaut) … a hedge between;

On or towards the South-east by a dwellinghouse called ‘Le Sommet’ and land owned by the Purchasers, a hedge between; and

On or towards the South-west and the North-west for a short distance by the remainder of said driveway the hedge between belonging to the Vendor.”

41. It is clear from this description (a) that the plot of ground sold extended 30 feet along the boundary with the Brehaut field and (b) that there was some of the strip of land which was conveyed for the driveway in the 1960 Conveyance on the South-western and North-western boundaries of the plot. But it appears also that the South-western boundary of the plot was at the hedge which was adjacent to the Northern-eastern side of the driveway as constructed and which was shown on photographs taken on 31 December 2008. Those photographs were lodged in the Royal Court and were shown to the Board (photos 6 and 7 in the AFR conveyancing file). This also tallies with Mrs Harrison’s uncontested evidence (para 16 above). It appears therefore that the plot which Mrs Harrison sold in 1984 took up the bulk of the width of the strip of land conveyed in the 1960 Conveyance for the driveway and will in all probability have made any vehicular access impossible within the residue, if any, of that strip of land. A comparison of the plan 2842 and the Cadastre plan by which the 1984 Conveyance was registered supports this view. The Board therefore is satisfied that the Court of Appeal was entitled on the evidence before it to conclude (a) that the driveway as constructed at the location in dispute was to a material extent built on land owned by third parties and (b) that there was a defect in the title which Mr and Mrs Lovering acquired in the 2009 Conveyance in that the land which Mrs Harrison alienated in the 1984 Conveyance materially reduced the only access route to which they had title. It follows that the appeal must fail.

The claim and this appeal

42. As a result of the findings by the Royal Court in relation to consequential loss, which were upheld by the Court of Appeal, the claim is essentially for legal fees, surveying fees, the purchase price of the plot of land which had been alienated in the 1984 Conveyance, and the cost of the earthworks and placing tarmacadam on the reacquired part of the driveway shown in the 1960 Conveyance. The Royal Court estimated those claims to be in the region of £36,000. The Board records its concern about the disproportionate cost of this litigation, involving as it has a second appeal. The Board also recalls its advice in the Guernsey case of A v R [2018] UKPC 4, in which (para 13) it expressed the view that there was merit in a review of section 16 of the Court of Appeal (Guernsey) Law 1961. Such a reform would at least place a constraint on parties incurring disproportionate costs in litigation.

Conclusion

43. The Board will humbly advise Her Majesty that the appeal should be dismissed.

Plan 2842 (30/12/2008)

LORD BRIGGS: (dissenting)

44. I would have advised that this appeal should be allowed.

45. As is apparent from Lord Hodge’s opinion, the single issue which is decisive of this appeal (on the negligence claim as pleaded) is the true construction of the 1960 Conveyance. This is because it was that transaction which for the first time created the now disputed western boundary of the strip of land which was to accommodate the driveway to the house still to be built on the land then being sold. Prior to 1960 the strip of land was part of the vendors’ property to the West. There being no case advanced that the boundary was subsequently altered by prescription, and there having been no further transaction between the vendors and the purchasers under the 1960 Conveyance, or by their successors in title, the boundary must have stayed the same as it was when the 1960 Conveyance was executed. That is the moment in time at which the disputed boundary crystallised. Although it is theoretically possible that Mrs Harrison might have conveyed something less than that strip of land to Mr and Mrs Lovering in 2009, I shall in due course explain why that possibility may be discounted.

46. I have the misfortune to disagree with the majority of the Board about the true construction of the 1960 Conveyance. I shall start by defining my terms, by reference to Plan 2842, which was annexed to the 1960 Conveyance, and is also annexed to the Board’s advice. I shall call the strip of land which was to accommodate the driveway “the Strip”. It is important to distinguish it from the driveway itself (“the Driveway”), which is a physical feature which probably existed in some form before 1960 but which in any event achieved its settled features by, at the latest, 1968 when Mrs Harrison arrived on the scene. Her evidence (not in dispute) is that it never thereafter moved. I shall call the whole of the land retained by the vendors in 1960 (out of which the Strip was carved by the 1960 Conveyance) Rougeval. I will call the land served by the Strip “La Roche Douvre”. That is coloured red on Plan 2842. The two properties lying to the east of the Strip I will call “the Brehaut Field” and “Le Sommet” respectively.

47. For convenience I will refer to the whole of the boundary separating the Strip from the Brehaut Field and Le Sommet as its Eastern boundary, even though it runs (starting from the North) South East, South West, then curving back to South East. Similarly I shall describe the boundary separating the Strip from Rougeval as its Western boundary, even though its general route (from the North) is roughly South South East, and the amount of its internal curvature is the central matter in dispute.

48. For convenience I shall use the following letters to indicate points on both the Eastern and Western boundaries of the Strip. Starting with the Eastern boundary, “X” marks its northerly point, where it adjoins La Roche Douvre (the red land). “Y” denotes the sharp corner where the boundary between the Brehaut Field and Le Sommet meets the Strip. “Z” denotes the Southern end of the eastern boundary of the Strip, where it meets the road (the “Route de Rougeval”). On the Western side there are three 10ft measurement marks on Plan 2842. Starting at the northern end, point A is where the boundary leaves La Roche Douvre, point B is at the first 10ft measurement, point C is at the second 10ft measurement and point D is where the boundary meets the Route de Rougeval at the Southern end of the Strip.

49. Lord Hodge’s opinion sets out the terms of the relevant parcels clause in the 1960 Conveyance in its original French. A reasonably faithful English translation is as follows:

“SECONDLY: a strip of land (shaded in blue, with measurements, on the said plan) and bounded to the North by the piece of land on the first item of this conveyance and to the SOUTH by the Route de Rougeval, in the said Fief de Huit Bouvées: LYING: on or towards the EAST by the said house, glasshouse and land owned by the said Vendors, boundary markers between them and on or towards the WEST by the said garden owned by the said Nicholas Brehaut and by a house called ‘Le Sommet’ with glasshouse and land owned by Mary Gallienne, hedges between them.”

50. It is common in unregistered conveyancing (and Guernsey appears to be no exception) to find parcels of land described both by a plan and by words. Where each method of description (viewed separately) leads to the same result, then no difficulty of construction arises. Sometimes the two work together, each filling in gaps left by the other or adding to the detail. But sometimes they point to different outcomes in terms of the extent and boundaries of the land being conveyed. In such a case it is a question of construction as to which should prevail, or be given the greater weight. Conveyancers frequently use well known phrases to resolve that issue. A plan may be referred to “for identification purposes only”. This usually means that the verbal description will prevail, where it differs from the plan. Or the land being conveyed may be described as “more particularly delineated on the plan annexed hereto” in which a case the plan will generally prevail over the verbal description.

51. But conveyancers may confusingly use both phrases together, as happened in Wibberley Building Ltd v Insley [1999] 1 WLR 894, 898. There the parcels clause stated that the land conveyed was “more particularly delineated for the purposes of identification only on the plan annexed hereto”. Lord Hoffmann said that this confusing description left it unclear whether the plan could be relied upon for the determination of precise boundaries. If it could not, he said (at p 896) that in such a case:

“if it becomes necessary to establish the exact boundary, the deeds will almost invariably have to be supplemented by such inferences as may be drawn from topographical features which existed, or may be supposed to have existed, when the conveyances were executed;”

52. Sometimes, as in the present case, there may be no express indication in the conveyance as to the relative importance of the plan and the verbal description, in ironing out any conflict or tension between the two. Again, topographical features may resolve the conundrum. Recourse to the position on the ground as at the time of the conveyance is not some special rule peculiar to conveyancing. It is simply the application of the general principle of construction, applicable to all documents, that the words must be read in context. Although a conveyance of land may have to be read and construed many years after it was executed, by which time the position on the ground may have changed, it is nonetheless that position on the ground at the time of execution which matters. This is because, where a conveyance creates a boundary for the first time, it works an immediate and permanent division of ownership, which can only thereafter be changed by a further transaction, or by prescription. It is also because the then position on the ground is that which, objectively speaking, the parties to the conveyance must be taken to have had in mind when choosing how to express the terms of the transaction in the document.

53. In Eastwood v Ashton [1915] AC 900, 906 Earl Loreburn said in a dispute about title to a small strip of land:

“We must look at the conveyance in the light of the circumstances which surrounded it in order to ascertain what was therein expressed as the intention of the parties.”

Commenting on this passage in Pennock v Hodgson [2010] EWCA Civ 873, at para 12, Mummery LJ said:

“Looking at evidence of the actual and known physical condition of the relevant land at the date of the conveyance and having the attached plan in your hand on the spot when you do this are permitted as an exercise in construing the conveyance against the background of its surrounding circumstances. They include knowledge of the objective facts reasonably available to the parties at the relevant date. Although, in a sense, that approach takes the court outside the terms of the conveyance, it is part and parcel of the process of contextual construction.”

He went on to acknowledge that extrinsic evidence may be discounted, but only where the terms of the conveyance are clear.

54. In Chadwick v Abbotswood Properties Ltd [2004] EWHC 1058 (Ch) the relevant Land Registry transfer identified the land being transferred solely by reference to a plan, without the qualifying phrase “for identification purposes only”. At paras 43-44 Lewison LJ said:

“The principles applicable to the interpretation of a transfer of real property are not open to serious doubt. A transfer, like any other contractual document, must be interpreted in the light of the background facts reasonably available to the parties. Although it has been said that extrinsic evidence is not admissible to contradict the words of a transfer where the language of the transfer is clear, this may need reconsideration in the light of the modern approach to the interpretation of contracts: Partridge v Lawrence [2004] 1 P & CR 14 per Peter Gibson LJ But in any event, the transfer in the present case is far from clear. Where the definition of the parcels in a conveyance or transfer is not clear, then the court must have recourse to extrinsic evidence, and in particular to the physical features on the ground. As Bridge LJ put it in Jackson v Bishop (1979) 48 P & CR 57:

‘It seems to me that the question is one which must depend on the application of the plan to the physical features on the ground, to see which out of two possible constructions seems to give the more sensible result.’

The question is one to be answered objectively: what would the reasonable layman think he was buying? Since the question must be answered objectively, it follows that evidence of the parties’ subjective intentions, beliefs and assumptions are irrelevant; as are their negotiations.”

55. The passage in the judgment of Peter Gibson LJ in Partridge v Lawrence at para 29 referred to above by Lewison LJ is as follows:

“Mr Callman placed some reliance on the remarks of Griffith LJ in Scarfe v Adams [1981] 1 All ER 843 at 851, where the Lord Justice said this:

‘The principle may be stated thus: if the terms of the transfer clearly define the land or interest transferred extrinsic evidence is not admissible to contradict the transfer. In such a case, if the transfer does not truly express the bargain between vendor and purchaser, the only remedy is by way of rectification of the transfer. But, if the terms of the transfer do not clearly define the land or interest transferred, then extrinsic evidence is admissible so that the court may (to use the words of Lord Parker in Eastwood v Ashton [1915] AC 900 at 913) “do the best it can to arrive at a true meaning of the parties upon a fair consideration of the language used”.’

With respect to that judge, the way he expresses the principle may not do sufficient justice to the now recognised principle, as stated by Lord Hoffmann, that one construes a document against the background knowledge which would have been available to the parties. To that extent extrinsic evidence of what is the background is always admissible.”

56. It is probably not necessary in the present case to decide the question whether there remains an exclusionary rule about extrinsic evidence of the type mentioned in Pennock v Hodgson and Scarfe v Adams. If it mattered I would conclude that it does not, for the reasons given by Peter Gibson LJ. But even if that were wrong, extrinsic evidence can hardly be excluded if, as here, it is actually identified in the conveyance as an aid to its meaning. Here the 1960 Conveyance described the Western boundary of the Strip expressly by reference to “bornes” (boundary markers). In the conveyancing jargon then in use in the Channel Islands, a “borne” is a boundary marker already in existence: see the Jersey Law Commission’s Consultation paper no 6 (September 2002), Schedule 1, in which “borne” is defined as a “boundary stone (previously established)”.

57. Applying those principles to the present case, there are findings of fact made by the Jurats about the position on the ground at the time of the 1960 Conveyance which may be summarised as follows. In 1960 there was already a track of some kind running from what was then a field on La Roche Douvre to the Route de Rougeval, serving the northern part of what was then all part of a single title from which both La Roche Douvre and the Strip were carved. This was not seriously challenged in the Royal Court. The track did not for the whole of its length “hug” the boundaries with the Brehaut Field and Le Sommet. In particular it cut the corner opposite point Y, at least between points B and C. It ran roughly as later shown on the 1963 Ordinance Survey map. In 1960 there were “bornes” (boundary markers) running along the western side of the track, which followed a much straighter line between points B and C than the pronounced bulge shown on Plan 2842. They had probably been put there for the specific purpose of marking out the boundary to be created by the 1960 Conveyance, between the Strip and Rougeval. In the triangle between the track and point Y the ground consisted of a bank, rising several feet above the level of the track. None of those factual findings were successfully challenged in the Court of Appeal, and the careful description of the Jurats’ reasoning in the judgment of the Royal Court leaves the reader in no doubt of their rationality, after the Jurats had conducted a vue de justice (site visit).

58. There is nothing which a reading of the 1960 Conveyance in a lawyer’s office would reveal about any conflict between the wording of the parcels clause and Plan 2842, in relation to the location of the Strip. The reader would see that the verbal description of the North, East and South boundaries of the strip coincided precisely with the relevant edges of the land marked blue on the Plan. The reader would assume that, in the verbal description of the Western boundary, the boundary markers ran along the western edge of the land marked blue, round the bulge between points B and C. But a reading “on the spot” in 1960 with the plan in the reader’s hand would immediately reveal the conflict between the line of the boundary markers and the line on the Plan, between points B and C. In particular the line of the boundary markers would have left ample space for a 10ft driveway to the East of them, without requiring the excavation of the raised bank in the triangle at point Y, whereas the curved line between points B and C on the Plan would have appeared to run so close to the raised bank as to require it to be excavated, before the purchasers could obtain vehicular access to their newly acquired property. In short, the boundary markers would have appeared to preserve the line of the then existing track between points B and C, whereas the line on the Plan would not.

59. The reader on the spot would then consider whether the conflict could be resolved by reference to the 10ft measurements on the Plan. But there are no measurements between points B and C, and the necessary conflict revealed by looking at the Plan on site would only lie between those two points. It was common ground that the Strip could not be 10ft wide along the whole of its length, in particular between points B and C, because that would create such a sharp corner at point Y that no vehicle could negotiate it, even if the raised bank was excavated. By contrast the boundary markers could have coincided with the line between points A and B and between points C and D.

60. An appreciation by a reader on the spot that the verbal description of the Western boundary of the Strip conflicted with that boundary as shown on the Plan, at least between points B and C, would not of itself resolve the question how the conflict should be resolved as matter of construction. But imagine that a dispute about it had arisen between the vendors and the purchasers, when the purchasers first arrived on site after completion in 1960. The purchasers would have pointed to the (probably freshly laid) boundary markers, to the impossibility (if the vendors were right) of obtaining vehicular access to their new property without substantial excavation, and to the existence of the track, whereas the vendors could only point to the line on the small Plan, lacking measurements at the critical point in dispute. I cannot conceive how that dispute as to construction could have been resolved in favour of the vendors.

61. In fact of course there never was any such dispute. When the house now known as La Roche Douvre was built in the 1960s the track was improved so as to become the Driveway, using the boundary markers as the Western boundary, exactly along the route which it now occupies, and the owners of Rougeval never complained, during the more than 40 years when it was used as such before 2009, and have still not complained. In 1984 Mrs Harrison sold the raised triangle of ground between the Driveway and point Y, plainly without the slightest intention to restrict her only access to La Roche Douvre in any way. It was of course part of the Strip, but not part of the Driveway.

62. By 2009 the boundary markers on the Western boundary of the Strip had been replaced by a substantial boundary consisting partly of hedge and partly of post and wire fence, with a gap in it roughly opposite point Y to enable the owners of Rougeval to make their own use of the Driveway (presumably with the permission of the owners of La Roche Douvre).

63. The remaining question is whether in the 2009 Conveyance Mr and Mrs Lovering received anything less by way of conveyance than the Driveway, as by then very well established. In my judgment they did not. The land called in 1960 the “strip of land” was in the 2009 Conveyance called “the Driveway”. It is (perhaps rather oddly) described as being separated from Rougeval by “boundary marks between”, but I agree with Lord Hodge that this was probably because of a conveyancing practice to use terms drawn from earlier conveyances in the root of title. That boundary was by then certainly marked out by hedge and fence, as the conveyancer would have seen when inspecting the site.

64. The respondents submitted that the reference in clause 5.4 of the 2009 Conveyance to what I have called the Western boundary as “South west, West, North west and South west” points to the line between points B and C still being very curved, as shown on Plan 4782 (which mimics Plan 2842), rather than very gently curved as apparent from the boundary of the Driveway. So it does, but no objective reading of the 2009 Conveyance on the spot could have led the reader to construe it as conveying a driveway along a different route from its actual route, through the by then mature hedge between the Driveway and the raised bank in the triangle opposite point Y, up and down that bank, and leaving the actual route of the Driveway between points B and C remaining landlocked in the ownership of the vendors.

65. The issue which, on the pleadings and the case as advanced by Mr and Mrs Lovering, is decisive of this dispute is whether in 2009 they received good title to the Driveway. In my judgment, for the reasons given above, they did. But the majority of the Board has reached a different construction of the 1960 Conveyance, with the result that the negligence claim succeeds. I suffer no discomfort in that outcome. Even if, as I have concluded, the 1960 Conveyance did convey both the Driveway as it now is together with the triangle at point Y, it did so by means of drafting that contained a serious ambiguity which would only be likely to be revealed, and then resolved, by a site visit. By 2009 Mrs Harrison’s sale of the triangle by the 1984 Conveyance had created a time bomb which was likely to explode (as it duly did) when the root of title was later inspected as a desk-top exercise (rather than on the spot), in which the sale of the triangle appeared to block all or most of the Driveway (as it appeared on the plans), apparently leaving La Roche Douvre without a satisfactory vehicular access. It was Mr and Mrs Lovering’s misfortune, but no fault of their own, that this time bomb (already 25 years old when they purchased in 2009) went off only when they came to sell in 2012. The detonation occurred during the investigation of their title by their purchaser’s lender. It is probable that it should have been uncovered by the appellants and defused when investigating their clients’ vendor’s title on their purchase in 2009, at no cost to them.

LADY ARDEN: (dissenting)

66. In this matter, and with great respect to the majority, I agree with Lord Briggs that the 2009 Conveyance contained no defect in title to the Driveway for the reasons that he gives. I would add the following points.

67. The judgment of the majority takes no account of extrinsic evidence in the form of the boundary markers on the ground at the time of the 1960 Conveyance even if they were not visible at the date of later conveyances. The Jurats were satisfied that there would have been markers although it was not clear what form they took (Judgment of the Royal Court, para 86). Under the law of England and Wales, this extraneous evidence must be considered whether or not the conveyance and plan are consistent and can be read together see the judgment of Lord Briggs para 55 and the judgment of Peter Gibson J in Partridge v Lawrence [2012] 1 P & CR 14. The rule about taking into account extrinsic evidence is mandatory (unless excluded), not permissive. The position in Scots may be different in this regard: see Gretton and Reid, Conveyancing, 5th ed (2018) paras 11-28, which gives the following example:

“to say that a property is ‘bounded on the south by the road known as Buchanan Street, Glasgow’ might require extrinsic evidence as to the location of Buchanan Street.” (Emphasis added)

68. However, the law on which Payne v Walsh drew was the law of England and Wales and not the law of Scotland.

69. The parcels clause for the Driveway refers to the plan annexed to the conveyance, and now annexed to the judgment of Lord Hodge. As Lord Hodge points out, this is stated to be “avec mésurage” which I agree indicates that the plan was prepared with a view to its showing not just the general location, but also the dimensions, of the Driveway, but only of course for the parts of the Driveway for which dimensions were given on the plan. I further agree that the measurements shown on the plan were thereby incorporated into the parcels clause. But there are points to note about that. First, the plan, which is a scale plan, crucially does not show measurements in the relevant dog-leg bend. Moreover, the plan confirms that the width of the Driveway at the dogleg at that point is visibly and materially greater than at the two points where the plan has the notation “10’0””. Second, neither the parcels clause nor the plan shows the nature of the boundaries of the adjoining properties other than the reference in the conveyance to the boundary markers. The other boundaries could have been walls. If, however, they were hedges or ditches, where did the ten-foot measurement start? The answer to that question could make a material difference to the right of access. This imprecision makes it likely that the parties, who must have inevitably seen the Driveway, had agreed to the sale of the Driveway in its physical location. Third, in any event, the description of the Driveway in the parcels clause is also dependent on boundary markers which are not shown on the plan. These three points taken singly or together make it less likely that the plan was actually to be the final word on the location of the Driveway at the critical point as opposed to its actual situation. The inclusion of a reference to the boundary markers is furthermore meaningless and otiose if the effect of the describing the plan as having measurements is to exclude the exercise of locating the boundary markers on site.

70. It is of course open to the parties to an instrument to agree to exclude any rule of construction. They could therefore agree to exclude the rule about taking account of extrinsic evidence. The Court of Appeal and the majority rely on the plan to the exclusion of any evidence on the ground. I respectfully do not consider that this interpretation of the 1960 Conveyance is justified. There are no words of exclusion and the internal reference to the boundary markers, which were not located on the plan, was a clear direction to inspect the site. Moreover, we were told that in Guernsey it is usual for those representing the purchaser to conduct a site inspection to see exactly what the purchaser would obtain, and I assume that this would have been the position in 2009 if not before. This practice would be otiose and meaningless in locating boundaries if the task had to be fulfilled solely by reference to an (incomplete) plan.

71. The location of the boundary markers was a question of fact which in accordance with the law of Guernsey was determined by the Jurats having regard to the physical features of the land. They were able to make findings as to the location of the makers, but those findings - which are unchallenged - are given no weight by the majority.

72. It is moreover inherently unlikely that the parties would have agreed to a Driveway which at the time it was conveyed was unsuitable for vehicular traffic because of the bank at the dog-leg that on the majority’s view would have been included in it. It is inherently unlikely that there was no inspection of the boundaries over the last 50 years.

73. The outcome in this case shows the wisdom of the Guernsey conveyancing practice of site inspection. It does not, as I understand it, regularly occur in Scotland where conveyancing is now by reference to a digitised map of Scotland. (The cadastral register which is common to Guernsey and Scotland is a register for taxation purposes, and not for property ownership). But even in Scotland it is recognised that site inspection is prudent in case there are, for instance, structures on the property for which no planning permission has been obtained (see Gretton and Reid, para 1-18).

74. On the basis that site inspection is the usual practice, the argument that the law should favour certainty through excluding extrinsic evidence is inconsistent with practice and is liable to produce results which the parties could never have intended, such as the result in the present case, which conveyed a right of access unsuitable for vehicular traffic.

75. I would have advised Her Majesty that this appeal should be allowed.