Introduction

1. This judgment follows a fully remote hearing conducted via Skype for Business on 10 June 2020. Mr Andrew Williams appeared for the Appellants and Mr Nicholas Mason for the Respondent. I am grateful to them both for their written and oral arguments. The hearing was deemed to be a public hearing, by reason of its listing and accessibility to the press and public, and it was recorded by the tribunal. Any person is entitled, with the permission of the tribunal, to listen to the recording in suitable court premises.

2. The Appellants appeal with permission granted by this tribunal against an order of the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) (“the FTT”) dated 15 November 2019. The FTT by that order directed the Chief Land Registrar to cancel the application dated 10 May 2017. That was an application made by the Appellants relating to title number WYK828030 for their registration as proprietors of part of the land in that title on the grounds of adverse possession, under Schedule 6 to the Land Registration Act 2002 (“the Act”). The Respondent is the registered proprietor under that title.

3. The Order was made following a trial of the issues raised in the application. In her decision dated 15 November 2019, the Judge held that even if the Appellants were to establish adverse possession for a period of 10 years preceding the date of their application, the application could not succeed because the Appellants did not satisfy the conditions of para 5(4) of Schedule 6 to the Act.

4. The particular reasons the Judge gave for her decision were, first, that para 5(4) only applied in the case of a dispute about the correct position of a boundary and there was no dispute about the boundary between the Appellants’ garden and the land that they claimed; and second, that para 5(4) required an applicant to prove that they reasonably believed that they had paper title to the land claimed, and the Appellants could not prove any such reasonable belief.

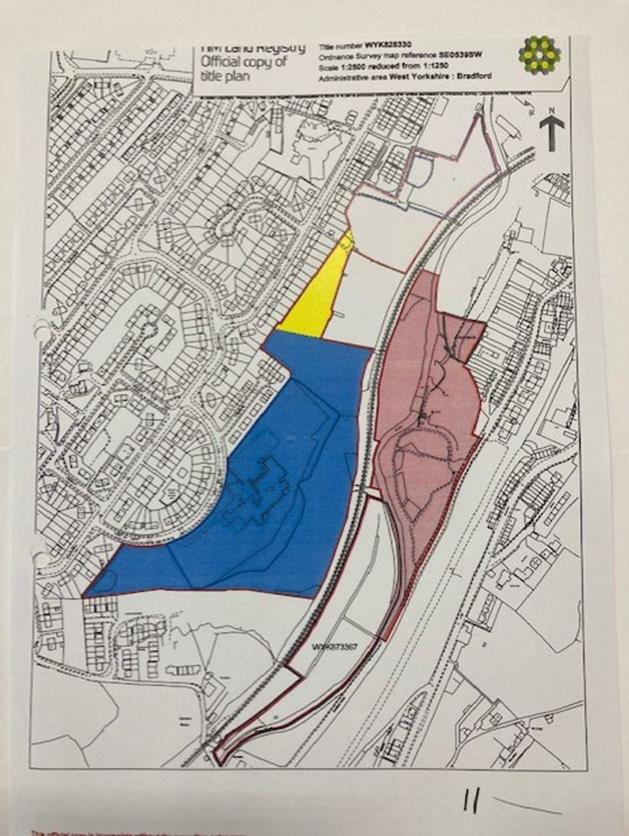

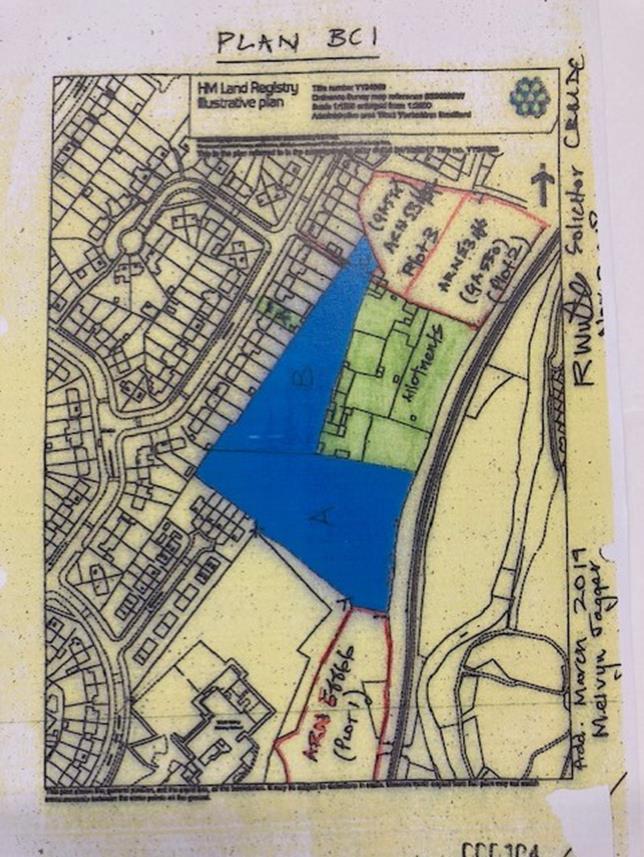

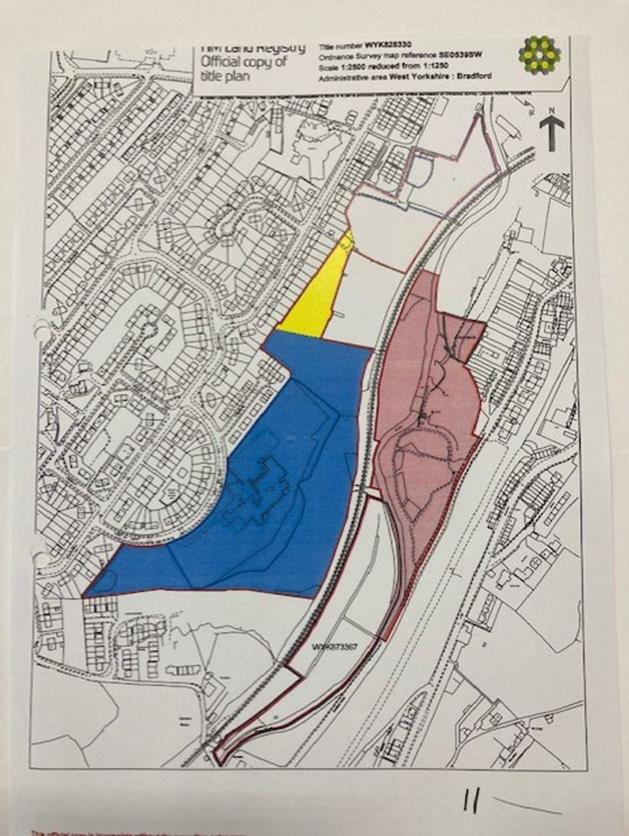

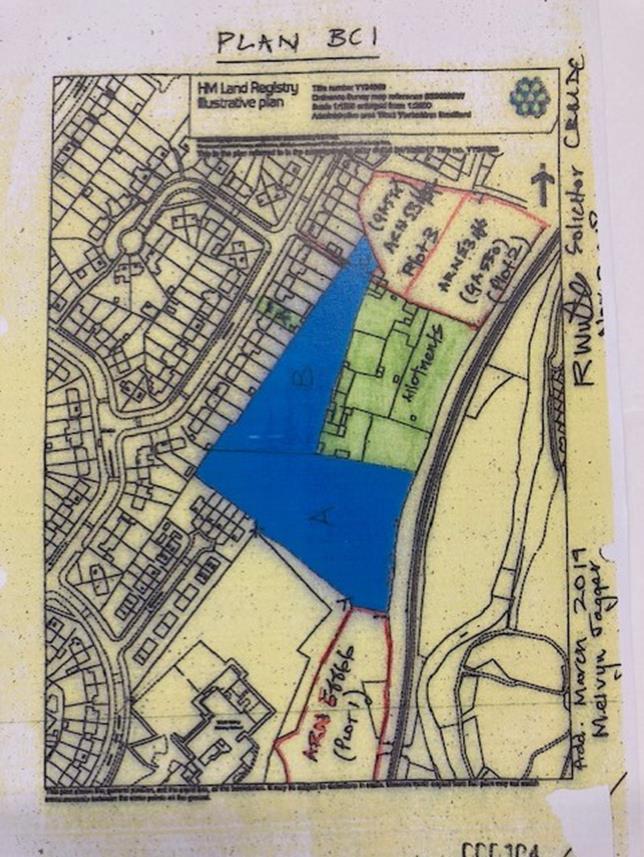

5. The Appellants have at all material times been registered as proprietors of a house, 135 Staveley Road, Keighley, under title WYK255622. I shall refer to that property as “No.135”. I shall refer to the claim land as “the application land”. The Respondent’s title comprises land known as Worth Primary School, Bracken Bank Crescent, Keighley. The land in that title is in two parts, separated by a railway line. It is shown on plan 1 annexed to this decision, coloured yellow, blue and pink. The application land is part only of the land to the west of the railway line, lying between the line and the gardens of semi-detached houses on Staveley Road. It is shown for convenience coloured blue on plan 2 annexed. On plan 2, No.135 is the single dwelling and garden lying to the west of the application land and is coloured green (not the allotment land to the east and north of the application land also coloured green).

6. There are three grounds of appeal advanced by the Appellants, which can be summarised as follows:

(1) If the Judge did not implicitly find that the Appellants had established 10 years’ adverse possession of the application land, she was wrong not to do so, and this tribunal should hold that adverse possession for upwards of 10 years is proved.

(2) The Judge was wrong to hold (i) that para 5(4) of Schedule 6 only applied where there was a dispute about the correct position of a boundary and (ii) that it required an applicant to prove that they had a reasonable belief that they had paper title to the disputed land. She should have held that the conditions in that regard were satisfied on the facts of this case and were not so limited.

(3) If the Judge did not implicitly find that the Appellants had proved a reasonable belief for upwards of 10 years that the application land belonged to them, she was wrong not to do so, and this tribunal should hold that such a reasonable belief was proved.

7. The way in which those grounds of appeal are framed reflects the fact that the Judge did not express any conclusions on the question of adverse possession or on the question of whether the Appellants had a reasonable belief that the application land “belonged” to them. It is evident that the Judge did not make an express finding on adverse possession because she concluded that, even if adverse possession was established, the Appellants’ case did not come within para 5(4). That was because it was not a dispute about the true position of a boundary. The Judge did not express a conclusion on the question of whether the Appellants had a reasonable belief that the application land belonged to them because she considered that this required a reasonable belief in paper title to the application land, and she addressed the question in that reformulated way.

8. It will be necessary to address the first and third grounds of appeal in detail in the event that the second ground of appeal succeeds. If, however, the second ground of appeal fails, whether because the Judge’s reasons were correct or for different reasons, it will be unnecessary to consider at any length the facts that she did or did not find. An applicant under para 5(4) must satisfy all the conditions there specified and if they fail on one such condition then their application to be registered must be dismissed.

9. It is convenient therefore to address the second ground of appeal first. It raises an important question of the true construction of Schedule 6 to the Act and is a matter of some general importance.

Schedule 6 to the Land Registration Act 2002

10. It is by now well-known that, among other important changes, the Act replaced the partly common law and partly statutory regime for adverse possession in the case of registered land and introduced a new statutory regime, based on the common law concept of adverse possession of land. In the context of registered land, the change was broadly speaking as follows and is contained within Schedule 6 to the Act.

11. Instead of a claimant having to prove 12 years’ possession of the land in question, adverse to all others including the current owner, whereupon the owner’s title would be extinguished and the claimant registered with a new freehold possessory title, the claimant has since October 2003 had to apply for registration on the basis of at least 10 years’ adverse possession. If the owner either fails to respond when notified of the application, or having responded fails to evict the claimant from the land before a continuous period of at least two further years’ adverse possession has occurred, the claimant is then entitled to be registered as proprietor of the owner’s title to the disputed land in his place.

12. If the owner does serve a counter notice in time following notice of the claimant’s application for registration, the application fails at that stage unless the claimant can bring themselves within one of three exceptional cases, which are set out in para 5 of Schedule 6. If the claimant cannot do so but they continue in adverse possession until two years after the rejection of the application, they are then entitled as of right to be registered as proprietor. If in the meantime they are evicted by the owner, no application for registration can succeed.

13. These changes make it much harder than under the Land Registration Act 1925 for a claim based on adverse possession to succeed. In general, the Act requires the owner of the land to be given a warning and gives him two years in which to evict the claimant. It is only in the three exceptional cases in para 5 that a shorter period of adverse possession than under the previous law will enable a claimant to succeed without the opportunity for the owner to recover possession. As stated by Henderson J in Baxter v Mannion [2010] EWHC 573 (Ch); [2010] 1 WLR 1965 at [42]:

“… the general policy of the 2002 Act was severely to limit the circumstances in which a squatter could acquire title to registered land, and to offer greater security of title for a registered proprietor than existed under the previous law. See generally the joint paper of the Law Commission and HM Land Registry, Land Registration for the 21st Century: A Conveyancing Revolution (2001) (Law Com No 271), chapter 14, and compare the observations of Lord Bingham of Cornhill in JA Pye (Oxford) Ltd v Graham [2003] 1 AC 419, para 2.”

14. Schedule 6 provides, so far as material, as follows:

“1(1) Subject to paragraph 16, a person may apply to the registrar to be registered as the proprietor of a registered estate in land if he has been in adverse possession of the estate for the period of ten years ending on the date of the application.

(2) Subject to paragraph 16, a person may also apply to the registrar to be registered as the proprietor of a registered estate in land if –

(a) he has in the period of six months ending on the date of the application ceased to be in adverse possession of the estate because of eviction by the registered proprietor, or a person claiming under the registered proprietor,

(b) on the day before his eviction he was entitled to make an application under sub- paragraph (1), and

(c) the eviction was not pursuant to a judgment for possession.

……

(4) For the purposes of sub-paragraph (1), the estate need not have been registered throughout the period of adverse possession.

2(1) The registrar must give notice of an application under paragraph 1 to –

(a) the proprietor of the estate to which the application relates,

(b) the proprietor of any registered charge on the estate,

(c) where the estate is leasehold, the proprietor of any superior registered estate,

(d) any person who is registered in accordance with rules as a person to be notified under this paragraph, and

(e) such other persons as rules may provide.

(2) Notice under this paragraph shall include notice of the effect of paragraph 4.

3(1) A person given notice under paragraph 2 may require that the application to which the notice relates be dealt with under paragraph 5.

(2) The right under this paragraph is exercisable by notice to the registrar given before the end of such period as rules may provide.

4 If an application under paragraph 1 is not required to be dealt with under paragraph 5, the applicant is entitled to be entered in the register as the new proprietor of the estate.

5(1) If an application under paragraph 1 is required to be dealt with under this paragraph, the applicant is only entitled to be registered as the new proprietor of the estate if any of the following conditions is met.

(2) The first condition is that –

(a) it would be unconscionable because of an equity by estoppel for the registered proprietor to seek to dispossess the applicant, and

(b) the circumstances are such that the applicant ought to be registered as the proprietor.

(3) The second condition is that the applicant is for some other reason entitled to be registered as the proprietor of the estate.

(4) The third condition is that –

(a) the land to which the application relates is adjacent to land belonging to the applicant,

(b) the exact line of the boundary between the two has not been determined under rules under section 60,

(c) for at least ten years of the period of adverse possession ending on the date of the application, the applicant (or any predecessor in title) reasonably believed that the land to which the application relates belonged to him, and

(d) the estate to which the application relates was registered more than one year prior to the date of the application.

(5) In relation to an application under paragraph 1(2), this paragraph has effect as if the reference in sub-paragraph (4)(c) to the date of the application were to the day before the date of the applicant’s eviction.

6(1) Where a person’s application under paragraph 1 is rejected he may make a further application to be registered as the proprietor of the estate if he is in adverse possession of the estate from the date of the application until the last day of the period of two years beginning with the date of its rejection.

(1A) Sub-paragraph (1) is subject to paragraph 16.

(2) However, a person may not make an application under this paragraph if –

(a) he is a defendant in proceedings which involve asserting a right to possession of the land,

(b) judgment for possession of the land has been given against him in the last two years, or

(c) he has been evicted from the land pursuant to a judgment for possession.

7 If a person makes an application under paragraph 6, he is entitled to be entered in the register as the new proprietor of the estate.”

Commentary

15. The operation of Schedule 6 and the purpose of para 5 were further summarised by Henderson J in Baxter v Mannion at [7] as follows:

“… notice of an application under paragraph 1 of Schedule 6 must be given by the registrar to the proprietor of the estate to which the application relates (paragraph 2(1)), and the notice must include notice of the effect of paragraph 4 (see below). The recipient of the notice may require that the application be dealt with under paragraph 5, in which case the applicant is only entitled to be registered as the new proprietor if one of the three conditions specified in paragraph 5 is satisfied. Those conditions are very limited in extent, and in broad terms confine the right of registration to cases: (a) where there is a proprietary estoppel in the applicant’s favour, and the circumstances are such that he ought to be registered as the proprietor; (b) where the applicant is for some other reason entitled to be registered as the proprietor; or (c) where the land in question forms part of a general boundary the exact position of which has not been determined under the Land Registration Rules 2003 (SI 2003/1417) …”

16. The Act was preceded by a Law Commission and HM Land Registry report, with draft Bill and commentary (“the Report”), to which Henderson J referred. The terms of the draft Bill are identical to the terms of the relevant provisions of Schedule 6 as enacted.

17. Both parties on this appeal have placed reliance on the contents of the Report. It is part of the objective legislative history of the Act and so is admissible as an aid to construction of the Act, though of course the views of its authors do not necessarily represent Parliament’s intention and the meaning of the Act.

18. In the summary of the main changes made by the Bill, the Report states, at para 2.74:

“… the squatter’s application will be rejected, unless he or she can establish one of the very limited exceptional grounds which will entitle him or her to be registered anyway. Of these exceptional grounds, the only significant one is where a neighbour can prove that he or she was in adverse possession of the land in question for ten years and believed on reasonable grounds that he or she owned it. This exception is intended to meet the case where the physical and legal boundaries do not coincide.”

19. The adverse possession provisions of the draft Bill are discussed in detail at chapter 14. The para 5 cases are described as exceptions to the general principle that if a counternotice is served by the proprietor in time the Registrar must dismiss the application for registration. Para 14.44 of the Report describes the para 5(4) exception as applying only where the land which is claimed by the squatter is adjacent to land which he or she owns and the boundary between the two properties is a general boundary. The Report then illustrates at para 14.46 the types of case that the exception is intended to meet with the following types of case:

“(1) The first is where the boundaries as they appear on the ground and as they are according to the register do not coincide. This may happen because –

(a) the physical features (such as the position of trees or other landmarks) suggest that the boundary is in one place but where in fact, according to the plan on the register, it is in another;

(b) when an estate was laid down, the dividing fences or walls were erected in the wrong place and not in accordance with the plan lodged at the Registry.

(2) The second is where the registered proprietor leads the squatter to believe that he or she is the owner of certain land on the boundary when in fact it belongs to the registered proprietor. Where the squatter has acted to his or her detriment in reliance upon the proprietor’s representation, he or she may be able to rely upon the estoppel exception explained above. However there will be cases where there is no such detrimental reliance, and the applicant will, therefore, have to rely on this third exception.”

20. The Report then suggests that the third exception (para 5(4)) is likely to make it easier to define the boundaries between properties, before explaining that the land claimed must be adjacent to land belonging to the squatter applicant and that the line of the boundary must not have been exactly determined. It further states at para 14.49:

“Where a landowner has gone to the trouble of having a boundary fixed under this procedure, then the register is conclusive as to the boundary and the justification for the third exception is, therefore, absent. One very good reason why a registered proprietor might wish to have the boundary exactly determined would be where the legal boundary of the land and its apparent physical boundaries did not coincide.”

21. As to the mental element required for the exception in para 5(4), the Report states, at paras 14.50, 14-51, that the squatter must establish that they reasonably believed that the claimed land belonged to them:

“At first sight this may seem to be a very demanding requirement. In practice it is unlikely to be.

Under the present law and under the Bill, any squatter will have to show the necessary animus possidendi to establish that he or she was in adverse possession. The animus that is required is ‘an intention for the time being to possess the land to the exclusion of all other persons, including the owner with the paper title’. If a person is in adverse possession of land under the mistaken belief that he or she owns it, that necessarily satisfies the animus possidendi for adverse possession. In other words, the animus that will be required to establish the third exception is no more than one specific form of the animus possidendi that is needed to satisfy the requirements of adverse possession.”

22. The parties also referred to the ninth edition of Megarry & Wade: The Law of Real Property at paras 7-097, 7-098, where the following commentary is given:

“… In relation to boundaries, therefore, acquisition of title by adverse possession can be justified for much the same reasons as it can in relation to unregistered land, and in particular, it quiets titles. The Land Registration Act 2002 permits a squatter to acquire title solely on the ground of adverse possession in one tightly drawn situation. To establish this third condition, the squatter, S, must show each of the following:

(i) The land to which the application relates is adjacent to land belonging to the applicant. This requirement restricts the condition to boundary disputes.

(ii) The exact line of the boundary between the two properties has not been determined under the procedure provided for in the Act and the Rules. In other words, the condition applies only to a general boundary. Once a boundary has been determined in accordance with the statutory procedure, the register is conclusive and the justification for the third condition no longer exists.

…..

The third condition will commonly apply in cases where the legal and physical boundaries of land do not coincide. Sometimes this happens because, e.g., on the construction of new housing, the fences or walls between the different lots are constructed in the wrong place. It can also happen, where the legal boundary does not follow the natural features on the land. Another case where the third condition might apply is where the registered proprietor leads S to believe that the parcel of land belongs to S. If S has acted to her detriment in reliance upon this representation (express or implied), she can rely upon the first condition (estoppel). But where there is no such reliance, S will have to rely on this third condition.”

The relevant facts

23. At the rear of the garden of No.135 is a fence, which separates No.135 from the open land to the rear. At the date of the FTT hearing, it was a fence with iron railings and a gate in it leading onto the open land, but the fence looks relatively new. The open land is part of the application land, though the application land is much more extensive and is irregular in shape. It amounts, the Judge thought, to up to about 2 acres of the land in the Respondent’s title.

24. On plan 2 annexed, the application land has letters showing different parts of the land. The lettering was added for the purposes of exposition at the trial, but the different letters do reflect physical features on the ground. Between parcels “A” and “B” is a fence that the First Appellant, Mr Dowse, claims to have erected long before the period of adverse possession on which he relies. Between parcels “B” and “C” is a track leading from the end of a lane running from Staveley Road to allotments. Parcel “A” was, historically, in different ownership from parcels “B” and “C”, though all were united in the Respondent’s statutory predecessor’s ownership in the 1960s.

25. There is accordingly a boundary between No.135 and part of parcel “B” of the application land. The Judge made no findings about the boundary but the relevant facts are not in dispute and are sufficiently clear. There is no indication in the registered titles of No.135 or the Respondent’s land that this boundary has been fixed under the statutory procedure in rules 118-122 of the Land Registration Rules 2003. Accordingly, it is a “general boundary”. That means that the registered plan shows the general position of the boundary, not its exact location. There is, self-evidently, no boundary between No.135 and parcel “A” or parcel “C” of the application land, though the application land, regarded as a whole, does have a boundary with No.135.

26. The Appellants claim to have been in possession of the application land since 1974. In 2001, they applied to HM Land Registry to have a title registered on the basis of 12 years’ adverse possession. That application was rejected by an Assistant Land Registrar by letter dated 26 April 2002. The letter explained to the Appellants’ then solicitors that it was not possible to register the Appellants with any class of title to the application land. The reasons given were that it was clear that the application land was only used for grazing, and the land was not in any event in the Appellants’ exclusive occupation. The Appellants disagreed with the conclusion.

27. The Judge considered that, to some extent at least, the Appellants had intensified their use of the application land since (and as a result of) the rejection of their first claim. She said that the First Appellant set about making access to the application land more difficult; possibly used the land for growing hay, and certainly used it for grazing and storing materials. The photographs show that, immediately adjacent to the fence at the rear of No.135 the Appellants had positioned a caravan and a trailer.

The application for registration and the FTT decision

28. The second application of the Appellants to HM Land Registry, made this time under para 1 of Schedule 6 to the 2002 Act, is dated 11 May 2017. It states that it is made under para 1 and that the Appellants intend to rely on para 5(2) and 5(4). The form ST1 explaining the Appellants’ case that was filed with the application states that they had installed new fencing to the rear of No.135. The part of the ST1 form that enables an applicant to require the application to be dealt with under para 5 of Schedule 6 in the event that a para 3 counter notice is given was not completed. No facts supporting reliance on para 5 were set out therein.

29. By the time the application had been referred to the FTT for determination, the Appellants were no longer relying on para 5(2) but were relying on para 5(4). The Appellants’ statement of case in the FTT identified the application land as “land at the rear of 135 Staveley Road, Keighley” edged red on a plan, but says nothing about whether the application land was adjacent to land that belonged to them or whether any boundary had been fixed under the 2003 Rules.

30. The Respondent’s statement of case in the FTT admitted the Appellants’ ownership of No.135 and that the “garden land alone abuts the land highlighted yellow on the Council’s title plan”. It denied that “the extent of the [Appellants’] adjacent land is sufficient to adversely possess the whole of the claimed land or any land whatsoever”. It asserted that the majority of land adjacent to the application land was owned by the Respondent.

31. By the date of the hearing, issue had been joined on whether the conditions in para 5(4) of Schedule 6 were all satisfied.

32. After referring to the intensified use of the application land since 2002, the Judge expressed her conclusion as follows:

“[59] However, and even assuming that Mr Dowse used the land exclusively for the 10 years before he made his application with the necessary intent to occupy, he does not satisfy the conditions set out in paragraph 5(4) of Schedule 6.

[60] Notwithstanding Mr Williams’ ambitious submission, it is clear in my judgment that paragraph 5(4) is intended to, and does deal with, the not uncommon situation where there is a dispute as to the exact position of the boundary between the applicant’s land and the disputed land, and where the applicant reasonably believed that he had paper title to this disputed land. This provision is, in a sense, a safety valve to deal with one of the problems associated with general boundaries. It is tightly drawn, and is limited in scope.

[61] The disputed land in this case extends far beyond the boundary with No. 135. There is no mistake in that boundary. In any event, Mr Dowse did not believe that he had paper title to the disputed land. He knew that he did not, which is why he applied to the Land Registry on two occasions for possessory title. To suggest that a belief in ownership by adverse possession is sufficient is to render the provision nugatory: paragraph 5(4) only comes into play when the applicant can show 10 years’ adverse possession. This is not enough under the 2002 Act: the applicant must go further and establish that he reasonably believed that he owned (in the sense of having paper title to) the land. Without this additional element, and unless he can bring himself within one of the two other conditions in paragraph 5, his claim will fail.”

The Application was therefore ordered to be dismissed.

The Appellants’ case

33. The Appellants’ case is deceptively simple and is as follows:

a. First, they had more than 10 years of adverse possession of the application land prior to 11 May 2017. That assertion raised factual and legal questions for the FTT to decide.

b. Second, the application land or part of it is said to be “adjacent” to No.135, which is land belonging to them. So sub-para (a) of para 5(4) is satisfied.

c. Third, the exact line of the boundary between No.135 and the application land has not been determined under the statutory rules. There is no dispute that that is so and accordingly sub-para (b) of para 5(4) is satisfied.

d. Fourth, for at least 10 years prior to the date of the application the Appellants reasonably believed that the application land belonged to them. Their evidence was that they so believed because they disagreed with the Assistant Land Registrar’s rejection of their previous claim. That raised a factual and legal question for the FTT to decide.

As I have explained, the FTT did not decide the factual and legal questions identified above. It decided that for other reasons the Appellants could not bring themselves within para 5(4).

34. Mr Williams submitted that the Judge was wrong to read into para 5(4) a limitation of the third exception to a case where there is a mistake in the position of the boundary. He further submits that the Judge was wrong to read sub-para (c) of para 5(4) as requiring a reasonable belief of the applicant that they owned the paper title to the disputed land. He argues that, applying the correct approach to construing the statutory provision, the language of para 5(4) is unambiguous in its meaning and the exception should therefore be applied in accordance with its literal meaning. If each of the conditions is severally satisfied, the Appellant are entitled to be registered with the Respondent’s title to the application land.

35. He accepts that “adjacent to” means, in this context, having a boundary with, not merely being in close proximity to, and submits that No.135 does have a boundary with the application land. Further, he says that condition (b) is satisfied, as is undisputed. As to reasonable belief, he submits that there is no language in the statutory provisions that requires the reasonable belief of the applicant to be that they have paper title to the disputed land and that this should not be read into the condition in the way that the Judge appears to have done. The application therefore turned on whether adverse possession for 10 years before the application was established and whether the Appellants reasonably believed for those 10 years that the application land belonged to them. He submits that the Judge either implicitly found in favour of the Appellants on those issues or, alternatively, was wrong not to do so.

36. As for the suggestion that the exception in para 5(4) is meant for and limited to boundary disputes, he again points to the fact that the statutory provisions do not say so and relies on the terms of the Report, which contemplate that they will apply in a case where there is a difference between the physical position of the boundary marked by features on the ground and the line of the boundary on a plan but also in a case where the applicant has been led to believe that “he or she is the owner of certain land on the boundary when in fact it belongs to the registered proprietor”. It is not, therefore, he submits, a provision that only applies to the incorrect positioning of a physical boundary. Mr Williams understandably did not place reliance, as Mr Mason did, on the statement in para 2.74 of the Report to the effect that this exception was intended to meet the case where the physical and legal boundaries do not coincide. Mr Williams does also rely on the opinion of the learned editors of Megarry & Wade, which seems to reflect the opinion of the Law Commission.

Discussion and decision

37. Condition (a) in para 5(4) of Schedule 6 is that the land to which the application relates is “adjacent to” land belonging to the applicant. On the basis of the boundary between No.135 and the application land, the Appellants appear to have a case on its satisfaction, at least on a literal reading of the words of the condition. The application land has a boundary with No.135 and so is “adjacent” to it. The reference in condition (b) to a boundary shows that “adjacent to” means “has a common boundary with”. Further, condition (b) is unambiguous and is agreed on the facts to be satisfied. If those conditions are satisfied, the application for registration will depend on whether the Appellants have established 10 years’ adverse possession in the reasonable belief that the application land belonged to them.

38. Considering conditions (a) and (b) together, however, it is instructive to see what their effect is. If, instead of No.135 and the application land having a common boundary, there had been a narrow road between them, owned by someone else, the Appellants’ application would fail. That is because the application land would then not be “adjacent to” No.135 within the meaning of para 5(4). The adverse possession of the Appellants and their reasonable belief could have been exactly the same as they were in fact, prior to May 2017, and yet the Appellants could not establish their entitlement under para 5(4) because the lands were not adjacent. That demonstrates that the justification for the exception in para 5(4) is nothing to do with the adverse possession as such, even where there is a reasonable belief in ownership of the disputed land, but depends on the fact of the common boundary.

39. Similarly, if in 2002, when the Appellants’ first application to be registered with title to the application land failed, the Respondent had reacted (as it might have done) by applying for the boundary between No.135 and its land to be fixed, and if the boundary had been fixed in consequence, the application of the Appellants in 2017 could not succeed, regardless of whether they had been in adverse possession and reasonably believed that the application land belonged to them. That clearly demonstrates that the exception in para 5(4) is concerned with the fact that there is (or may be) uncertainty about the true position of the common boundary.

40. Objectively, the cases in para 5 of Schedule 6 are exceptional cases, in which after only 10 years’ adverse possession, without warning to the proprietor and despite the general hardening of legislative policy against squatters, the squatter can acquire the proprietor’s title. In that context, one would expect to find some clear justification in the conditions for the exceptional treatment in those cases, not conditions that are merely incidental to the core justification of adverse possession.

41. On that basis, reading conditions (a), (b) and (c) together, it is clear that the exception is to the effect that the applicant was justified in believing that the true position of the boundary was where he believed it to be. The exception is necessarily to do with the position of the boundary, and not simply giving effect to a reasonable belief of the applicant as to ownership, otherwise conditions (a) and (b) would be otiose. It would otherwise be bizarre that Parliament should intend to allow the proprietor to be dispossessed after only 10 years, without warning, if part of the disputed land adjoined the applicant’s land but not if it did not, and not in a case where the boundary had been fixed, even if the claim to adverse possession had nothing to do with the general boundary between the applicant’s land and the disputed land.

42. This construction in my view does no violence to the language of the statute and does not need to be justified on that basis. Condition (a) is that “the land to which the application relates” is adjacent to the applicant’s land. That is clearly a reference to the whole (or possibly substantially the whole) of the disputed land, not simply part of it. Thus, the whole (or substantially the whole) of the disputed land would have to be capable of being described as “adjacent to” the applicant’s land for the condition to be satisfied. That is clearly the case when the land in dispute is land within what would be regarded as the general boundary area between the two parcels of land, but it is not the case where only a small fraction of the land in dispute adjoins the applicant’s land, as is the case here. The claim to adverse possession of the greater part of disputed land that does not adjoin the boundary can have nothing to do with the position of the boundary between the two parcels. Even if the claim succeeds, the disputed land does not become part of the applicant’s own land, thereby changing the boundary; the applicant is substituted as registered proprietor of the owner’s land, and the boundary between the parcels remains unchanged.

43. What then of the reference in the Report and in Megarry & Wade to the alternative case where there is no discrepancy between the true boundary line and the appearance on the ground but a representation made by a landowner on the basis of which his neighbour believes that part of the landowner’s land belongs to him? That is not, in substance, a different case from the first example given in the Report. It is notable that the paragraph of the Report on which the Appellants rely states that the squatter is led to believe that he owns “certain land on the boundary”. The applicant must still have possessed the land concerned exclusively for upwards of ten years, and that land will still have to be adjacent to the applicant’s own land. So the second example is concerned only with land along the boundary. The exact line of the boundary not having been fixed by the Registrar, the neighbours’ understanding about where the line of ownership divides is different from the exact position of the boundary. The applicant reasonably believes that he owns the land because he has been led to believe that by his neighbour. The only difference is that instead of the physical features on the ground giving a misleading appearance as to where the true boundary lies, the neighbour misleads the applicant into thinking that the boundary lies in the wrong place.

44. If, as I consider to be the case, the exception is limited to land in the area of the general boundary between the applicant’s land and the registered proprietor’s land, it is a relatively narrow exception to the general rule that if the proprietor serves in time a counter-notice under para 3 the application will fail. The application can only succeed if one of the three exceptional cases in para 5 is met. These are that it would be unconscionable for the proprietor to dispossess the applicant because of an equity by estoppel; that the applicant is entitled for some other reason apart from adverse possession to be registered; and that the para 5(4) exception applies. In that context, it is unsurprising that the third exception proves to be a narrow one. An applicant needs to establish a clear basis of entitlement as against the registered owner to have title to the disputed land at that early stage.

45. Looked at in this way, the requirement in sub-para (c) of para 5(4) will often be satisfied where the applicant has paper title to the land and reasonably believes that the disputed land along the boundary is within his paper title. That would be the paradigm case but, as the Law Commission has identified, it is not the only set of circumstances in which the exception should apply.

46. There is nothing in the language of para 5(4) to limit the application of the exception to a case where the applicant reasonably believes that he has paper title to the disputed land. On the contrary, para 5(4) consistently uses the language of “belonging to”, not the words “title” or “ownership”. In sub-para (a), the disputed land must be adjacent to “land belonging to the applicant”; in sub-para (c) the applicant must reasonably believe that the disputed land “belonged to him”. It is understandable that the draftsman did not use the concept of the applicant’s registered title because his land might be unregistered land. Para 5(4) is not limited in its application to a case where both adjacent parcels of land have registered titles, though the disputed land must be registered land. But in my judgment the draftsman has deliberately used the broader concept of “land belonging to” the applicant because it is not necessary that the applicant believe that he has a paper title to the disputed land. This could therefore include a case where the applicant reasonably believes that the disputed land belongs to them because of at least 12 years’ adverse possession before 13 October 2003.

47. The Judge thought that this was an impossible construction of para 5(4)(c) as it would mean that the requirement added nothing to the underlying requirement for 10 years’ adverse possession. However, that is not the case. Although in some cases the requirement for an animus possidendi may coincide with a reasonable belief in ownership, it is not necessarily the case. A person may be in adverse possession even though he knows full well, until the expiry of the period of 10 or 12 years, that he has no title: it is an intention to possess the land to the exclusion of others that is required. The added requirement in para 5(4)(c) is that of reasonable belief throughout the period of adverse possession (not only at its end) that the land belongs to the applicant. It has the effect of limiting the third exception to cases of genuine and understandable mistake as to ownership enduring for at least 10 years. In any event, there is no principled basis for excluding an applicant who has equitable or undocumented ownership of his own land that is adjacent to the disputed registered land: “belonging to” must have the same meaning in both places that it appears in para 5(4).

48. In my judgment, therefore, the application land in this appeal is not “adjacent to” land belonging to the Appellants, within the meaning of para 5(4)(a) of Schedule 6. Only a very small part of it was within the area of the general boundary with No.135. The land to which the application relates is not adjacent to land belonging to the Appellants, within the meaning of para 5(4). On that basis, the Appellants cannot succeed even if they prove adverse possession and a reasonable belief that the application land belonged to them for the period from 2007 to 2017. It is therefore strictly unnecessary to consider in detail grounds 1 and 3 of the appeal, as the appeal must fail for the reasons that I have given.

The factual findings of the Judge

49. Had it been necessary to consider whether the Appellants had proved that they were in adverse possession of the land, I would have held that it was not implicit in the decision of the Judge that she found proved adverse possession of all the application land. She made no express finding and it is not otherwise clear from the decision to what extent the claim to have been in adverse possession would have been established.

50. Mr Williams pointed out that there were some factual findings made, and some undisputed evidence that the Judge recounted, such as the fact that Skipton Properties Limited paid Mr Dowse £1,000 in 2005 for the right to come onto the application land to lay a sewer, and that Mr Dowse challenged neighbours in 2003 about their right to enter his land. Much of the Appellants’ evidence about use before 2007 was disputed by Mr Jagger of the Respondent, but he was unable to give evidence about use after 2007. Nevertheless, the positive findings about use in the period 2007 to 2017 were very limited, and amount to nothing more than this:

“It seems very likely that, having failed in his first attempt to obtain title by adverse possession, Mr Dowse set about making access to the disputed land very much more difficult, and to have intensified his user of this land, possibly for growing hay, certainly for grazing and storing materials.”

51. The Judge, in later refusing permission to appeal, said:

“If I had to reach a decision on the point, I would have found that the Applicants had been in adverse possession for ten years prior to the application.”

52. I agree with the Respondent that this indication cannot be a substitute for a reasoned determination of the issue within the decision itself. The application land was a large area, with distinct parcels. If the Judge was to find that there was adverse possession, the Respondent was entitled to reasons why, as regards each part of it and in view of the different uses that were found to have been made at various times, such use was sufficient, and why it was accompanied by the requisite intention to possess. The Respondents might wish to appeal on the basis of such a conclusion and could not do so on an informed basis without the necessary findings and reasons. They cannot appeal a refusal to grant permission to appeal.

53. As for ground 3, the Judge did not address the question of whether it was reasonable for the Appellants to believe throughout the period 2007 to 2017 that the application land belonged to them. That was because she addressed the question on the basis that it was necessary to have a reasonable belief of paper title. In the light of the Assistant Land Registrar’s letter of 26 April 2002, and despite the Appellants’ determination to make it very much harder for others to gain access to the application land thereafter, there was a real question as to whether by 2007 the Appellants could reasonably have believed that the land belonged to them. It would be necessary for them to prove that, at all times from 2007 to 2017, they did in fact so believe and that such belief was reasonable.

54. Mr Williams submitted that since, as a result of the April 2002 letter, the Appellants had the intention to possess the application land to the exclusion of all others, their belief as to ownership was necessarily reasonable, and he relied on paragraph 14-51 of the Report (para 21 above) in this regard. I do not consider that the comments of the Law Commission support his argument, even if the necessary animus possessionis is assumed. The comments are made in the context of someone being mistaken about the true position of a boundary (“… under the mistaken belief that …”), or as to his ownership of land at the boundary as a result of something done or said by his neighbour. In that context, it is easy to see that if the necessary intention to possess to the exclusion of all others is proved there is likely also to be a reasonable belief that the disputed land belongs to the applicant. That is all that para 14-51 of the Report is saying. It is not saying that, in the law of adverse possession generally, a person who intends to possess land will reasonably believe that he owns it.

55. Whether the Appellants could prove belief from 2007 that the application land belonged to them, and if so whether such belief was at all times objectively reasonable in the circumstances, are both issues that the decision did not impliedly determine and where the necessary findings and analysis do not exist.

56. In those circumstances, if the Appellants had succeeded on Ground 2 of their appeal it would in my judgment have been necessary to remit the decision to the FTT for those findings and determinations to be made. However, since the Appellants failed on Ground 2, no such remission is needed and their appeal is dismissed.

The Hon Mr Justice Fancourt

23 June 2020

PLAN 1

A close up of a map

Description automatically generated

PLAN 2

A picture containing text

Description automatically generated