Introduction

1. The land which forms the subject of this application is Trengove Stables, Trengove Farm, Constantine, Falmouth, Cornwall TR11 5QR (“the application land”). It is owned by the applicants, Tracey Rickard and Kate Thompson.

2. The application land was formerly part of Trengove Farm (“the farm”) which is owned by the objectors, Roger Collins and Gwendoline Collins. Mr Collins sold the application land to the applicants on 20 February 2004 subject to a restrictive covenant (“the restriction”) that stated:

“The Transferee shall not build or allow to be built on the Property any building or structure whatsoever, including garages, outhouses, sheds and conservatories, without first obtaining the written consent of the Transferor or his successors in title.”

3. The applicants obtained planning permission on 12 November 2019 for “Conversion of a redundant stone farm building into a dwelling” (“the permission”) but Mr Collins has refused to give his consent so they are prevented from implementing the permission by the restriction.

4. On 3 February 2020 the applicants applied to the Tribunal for discharge of the restriction under ground (aa) of section 84(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925 on the basis that it impedes a reasonable use of the application land.

5. The parties have not wished to incur the cost of valuation evidence and they have agreed that the Tribunal’s initial determination should be confined to the issue of whether the restriction secures practical benefits of substantial advantage to the objectors. Should I determine that issue in favour of the objectors it would not be necessary for the parties to submit evidence on the value of the restriction in monetary terms in order to determine whether that value was substantial for the purpose of assessing compensation.

6. Witness statements have been submitted by Ms Thomson on behalf of the applicants and by Mr Collins on behalf of the objectors. Legal submissions have been made on behalf of the applicants by Mr Sam Phillips of counsel and on behalf of the objectors by Mr Greville Healey of counsel.

7. I carried out an unaccompanied inspection of the application land and the farm on 16 September 2020 and thank the parties for facilitating that opportunity.

Factual background

8. The farm is situated in a rural area some eight miles west of Falmouth. Road access is by narrow lanes between Cornish hedges, typical of the area. At the centre of the farm, some 350 metres from the road down a gated track (“the track”), is the detached stone farmhouse and farm buildings occupied by the objectors. The main farm yard, adjacent to the farmhouse, comprises a range of stone barns, sheds and more modern buildings. On the opposite side of the track is a large portal frame livestock building.

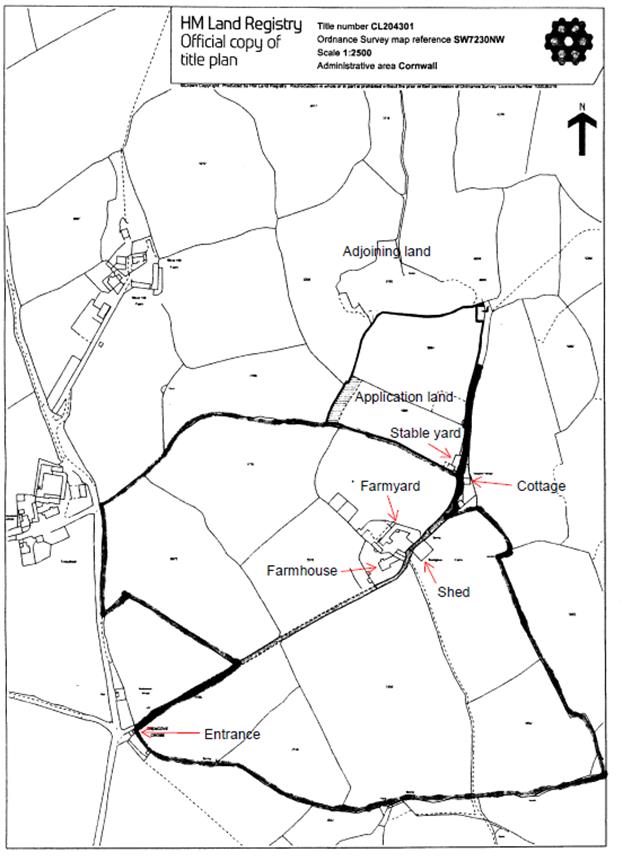

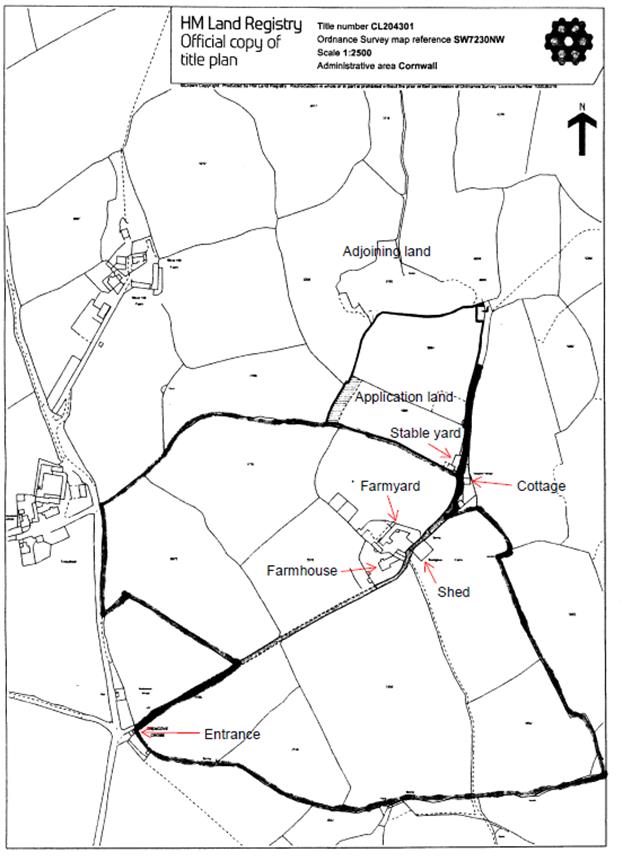

9. The farm was originally owned by Mrs Collins’ father and she has lived there most of her life. Mr Collins moved there in 1965 and took a tenancy from his father-in-law. At that stage it extended to 69 acres including the farmhouse and farm buildings.

10. Following the death of his father-in-law in 1995, Mr Collins purchased the farm from the estate in 1996. Ownership was transferred into the joint names of the objectors in May 2004. In 2004 and 2005 four parcels of land were sold off, including two small parcels adjacent to the road entrance.

11. The other two sales were blocks of land situated at the north end of the farm, beyond the farmhouse, and accessed by the track which passes it. The largest block was sold to the objectors’ son (“the adjoining land”) and the smaller block of 4.6 acres is the application land. Both sales included rights of access over the track and covenants to restrict building. The track owned by the objectors therefore gives access to the farmhouse and buildings, the application land, the adjoining land, and also to Trengove Cottage (“the cottage). The cottage is located across the track directly opposite the application land and has been in third party ownership since Mrs Collins’ father sold it in 1965.

12. A plan of the farm at Appendix 1 shows the locations of the various properties.

13. The track runs for some 630 metres from the road to its end at a building on the adjoining land. A public footpath runs along the track and continues beyond it. Measurements of distance between various points on the track are disputed, but my own estimations are that the farmhouse is some 330 metres from the road, with the entrance to the farm buildings a further 30 metres beyond. As far as this point the track has, in the past, been partly concreted. I estimate that the cottage and application land are situated a further 100 metres down the track which, from the farmyard onwards, has a simple stone surface. The track has a number of gates across it, I presume to assist with security and livestock management. I counted four that might be closed between the road entrance and the location of the application land and cottage.

14. The application land comprises two paddocks, with a levelled training area in the corner of one paddock, and a small yard with buildings (“the stable yard”). It was sold for £22,500 with the benefit of a right of way at all times over the track, subject to the transferee paying a contribution towards the maintenance according to user.

15. The buildings in the stable yard with the benefit of the permission, as I observed them during my inspection, are a small, low single storey shed and an attached lean-to structure slightly offset behind. The stone shed has rendered stone walls on three sides and a monopitch corrugated steel roof. The fourth side faces onto the track and is partially infilled with blockwork and corrugated steel sheeting around two stable doors and a wider opening. The building is shown on plans to be 13.6 metres long by 4.6 metres wide. On inspection it appeared to be out of use but not derelict or dilapidated.

16. The attached lean-to structure is a partly open sided monopitch construction, with timber uprights, roofed and clad mainly with corrugated steel and some perspex sheets. The dimensions are shown on plans at 14.9 metres in length and 3.9 metres in width. When I inspected, this shed was in use for general stable management and had a horse in one end.

17. To the rear of the lean-to structure is a small concrete yard and a small building housing two stables. The yard is accessed from the track over a concrete apron.

The proposed development

18. In July 2018 the applicants submitted an application to Cornwall Council (“the 2018 planning application”) for consent to the conversion of the stone shed, described as a “redundant farm building”, into a dwelling together with stables/store. The original design was for a rectangular two storey residential building with stables at ground floor level to the rear and a car port at the front. The majority of the living space was at the first floor level. The design was subsequently modified to a single storey ‘L’ shaped building for purely residential use. Permission was refused on 22 May 2019 for the following reason/s:

“The proposed conversion and extension of this former agricultural/horiscultural (sic) building would be tantamount to the construction of a new dwelling in the countryside and combined with the associated domestic paraphernalia would give rise to a detrimental change in character thereby harming the character and intrinsic beauty of the immediate surrounding countryside contrary to the aims and intentions of Policies 1, 2, 3, 7, 12 and 23 of the Cornwall Local Plan Strategic Policies 2010-2030 and paragraphs 8, 78, 79 and 170 of the National Planning Policy Framework 2019.”

19. A further application was submitted in August 2019, following pre-application advice from a planning officer. The design had been changed to a ‘T’ shaped single storey timber clad residential building with revised windows. Floor plans for the proposed residential unit show a new opening through the rear of the stone shed leading into a kitchen/diner sited within the current lean-to shed. The application received conditional permission on 12 November 2019 subject to standard conditions.

The law

20. Section 84 of the Law of Property Act 1925 provides, so far as is relevant:

“84(1) The Upper Tribunal shall … have power from time to time, on the application of any person interested in any freehold land affected by any restriction arising under covenant or otherwise as to the user thereof or the building thereon, by order wholly or partially to discharge or modify any such restriction on being satisfied-

…

(aa) that (in a case falling within subsection (1A) below) the continued existence thereof would impede some reasonable user of the land for public or private purposes or, as the case may be, would unless modified so impede such user; or

…

and an order discharging or modifying a restriction under this subsection may direct the applicant to pay to any person entitled to the benefit of the restriction such sum by way of consideration as the Tribunal may think it just to award under one, but not both, of the following heads, that is to say either –

(i) a sum to make up for the loss or disadvantage suffered by that person in consequence of the discharge or modification; or

(ii) a sum to make up for any effect which the restriction had, at the time, when it was imposed, in reducing the consideration then received for the land affected by it.

(1A) Subsection (1)(aa) above authorises the discharge or modification of a restriction by reference to its impeding some reasonable user of the land in any case in which the Upper Tribunal is satisfied that the restriction, in impeding that user, either -

(a) does not secure to persons entitled to the benefit of it any practical benefits of substantial value or advantage to them; or

(b) is contrary to the public interest;

and that money will be an adequate compensation for the loss or disadvantage (if any) which any such person will suffer from the discharge or modification.

(1B) In determining whether a case is one falling within section (1A) above, and in determining whether (in any such case or otherwise) a restriction ought to be discharged or modified, the Upper Tribunal shall take into account the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permissions in the relevant areas, as well as the period at which and context in which the restriction was created or imposed and any other material circumstances.

(1C) It is hereby declared that the power conferred by this section to modify a restriction includes power to add such further provisions restricting the user of or the building on the land affected as appear to the Upper Tribunal to be reasonable in view of the relaxation of the existing provisions, and as may be accepted by the applicant; and the Upper Tribunal may accordingly refuse to modify the restriction without some such addition.”

The application

21. The applicants seek the discharge of the restriction under ground (aa) on the basis that it impedes a reasonable use of the application land for the provision of residential accommodation and does not secure any practical benefit of substantial advantage to the objectors and/or that the restriction is contrary to public interest. They state that they would not object to the imposition by the Tribunal of a condition that the application land only be used as a single private dwelling house.

22. The applicants also state that it is arguable that the restriction does not impede the use of the application land for residential conversion in any event since they do not propose to construct any ‘new’ buildings, but only to convert existing redundant buildings. I will return to that point when I consider whether the restriction impedes the proposed use.

The grounds of objection

23. The objectors have provided evidence of the objections they submitted to both planning applications.

24. They point out that it is only 16 years since the applicants purchased the application land from Mr Collins, subject to the restriction and, although the parties are essentially the same (with Mrs Collins now a joint owner), the applicants now seek to have the covenant wholly discharged. The restriction was imposed in the context of the sale-off of part of a larger piece of land retained by the covenantee, which was and is where he lives, and where the sold part can only be accessed by passing through the objectors’ retained land and buildings, near their residence over a private access, albeit with a public footpath.

25. The immediate area is predominantly agricultural, with a low population density and the potential impact on the objectors’ amenity of a new household with more vehicular movements through the farm and more general disturbance arising from daily activities, is of concern. The objectors argue that their ability to prevent this is a substantial benefit of non-monetary value.

26. In this case the grounds of objection are relevant to at least two of the matters of which the Tribunal must be satisfied before it can order the discharge of the restriction. In particular, the impact of the proposed use on the amenity of the farm is relevant to the questions whether the use is a reasonable one, and whether by preventing it the restriction secures a practical benefit of substantial value or advantage. Despite the overlap between these issues, I will address them separately, as the parties did.

Is the proposed development a reasonable use of the land for public or private purposes?

27. The applicants argue that provision of residential accommodation is a reasonable use for the application land, illustrated by the fact that the permission was granted on the basis that the proposed works fall within the development plan and pattern of permissions within the area. In support of this proposition, the applicants rely on extracts from the Cornwall Local Plan, 2016 - 2020 (“the 2016 local plan”) and in particular the Falmouth and Penryn Community Network Area section which refers to the importance of using or developing sites on which there are currently buildings.

28. The 2016 local plan requires an average of 2,625 homes to be constructed per year. Delivery of residential accommodation in Falmouth and Penryn (among other areas) is listed as the top priority for development in Cornwall up to 2030 and housing is listed as Objective 1 in the Falmouth and Penryn Community Network Area.

29. The applicants point out that the restriction was imposed prior to the 2016 local plan at a time when the demand for housing was significantly lower. Copies were provided of nine permissions granted in the locality between July 2017 and March 2019 for residential conversion or construction at rural sites.

30. Mr Phillips submits that reasonableness for the purpose of ground (aa) is a broad concept and that using the dilapidated stable building at the application land for housing, enabling the applicants to continue to use the remainder for the care of their horses, is reasonable. He cites the observation of the Tribunal (Judge Cooke and Mr Trott FRICS) in Jackson & Jackson v Roselease Ltd [2019] UKUT 273 (LC) at [40]:

“The use of derelict buildings for housing appears to us to be reasonable, as does the conversion of unsightly structures into new buildings that are in keeping with their surroundings. We have no hesitation in finding that the use impeded by the covenants would be reasonable.”

31. The objectors argue that, in this location, the use of former farm buildings as a dwelling is not reasonable. The application land is on a farm, which is the objectors’ private residence. A new dwelling house on the farm would be an unwelcome intrusion and would have a marked negative impact on the amenity of the farm and the privacy of the objectors’ home.

32. When I first looked at a plan and satellite view of the farm I noted that the location of the stable yard, immediately opposite the cottage, seemed to suggest de facto that it was a suitable location for a residential property. On inspection, however, it was apparent that the track by which both properties gain access from the road is functional as a farm track but not ideally suited for residential use. The fact that gates across the track are closed for security and livestock management is evidence that shared access must fit in with its use by the objectors in their farming activities.

33. In Roselease the permitted residential conversion was of a derelict Dutch barn and outbuildings, no longer in farming use and with independent road access. In this case the application land has been in continual use as a stable yard, albeit the stone building may technically be declared redundant now, and access to it is by rights across land owned and used by others. The issue is not whether, in general, the use of former farm buildings for residential purposes is reasonable, but whether the particular use which is proposed in this location is reasonable. The applicants are able to rely on the planning decision to demonstrate that the use is acceptable in planning terms, but that is not conclusive. The issue of reasonableness is less straight forward in this case.

34. I have previously described the buildings and the location, both of which struck me during my inspection as surprising choices for a residential building conversion. In its objections to the 2018 planning application Constantine Parish Council (“the parish council”) stated:

“Constantine Parish Council does not believe the existing building is either worthy of retention or would result in ‘enhancement’ of the immediate setting as required under Policy 7 of the Cornwall Local Plan. The proposal would also appear to be in conflict with Policy 21 of the Local Plan, given that the site is not in a sustainable location in respect of access to services and facilities. In essence the Council feels that this is an application for a new home in the countryside which is not normally permitted unless there is an essential need for a rural worker to live at the location (and no evidence of a need for such a dwelling has been put forward). Given the distance to the nearest settlements that provide them and despite the apparent lack of access to the highway, future occupants would be reliant upon the private vehicle to access services, goods, facilities and employment. …”

35. The parish council made the same objection to the subsequent application which gained the permission, but no other consultees had objections. Public comments were a mix of support and objection, including from the objectors and members of their family.

36. From the evidence available to me the main difference between the 2018 planning application and the subsequent permission is that the building was redesigned, under guidance of a planning officer on his pre-application site visit, to be a ‘T’ shape, with timber cladding and better window design. I am not clear how this addresses in full the reasons given for refusal of the 2018 application (that the proposal was “tantamount to the construction of a new dwelling in the countryside” which “would give rise to a detrimental change in character”). There is no officer report on the Cornwall Council planning website to explain the decision.

37. I conclude that the comment at [159] in Re Bass Ltd’s Application [1973] 26 P&CR 156, applies in this case:

“…Many planning permissions have got through by the skin of their teeth, and I think that the assistance to be derived from a planning permission at this stage of things is little more than the negative assistance of enabling it to be said that at any rate there was not a refusal.

…”

38. I was not provided with a location plan or further interpretation to assist me in understanding how the nine planning permissions supplied are evidence of a pattern for the grant of permissions in the area. The parties were subsequently invited to comment on the information available on the planning website of Cornwall Council giving context to those permissions. This revealed that the permissions are all located within the rural area surrounding the village of Constantine, but eight concern sites and properties within or adjacent to existing small settlements and with easy access to a public road.

39. Two of those permissions have occupancy conditions, one for use as a holiday let and the other for use by family members and guests of the adjacent owners. The other six unrestricted permissions include a certificate of lawfulness for use as a dwelling, replacement of a caravan with a dwelling, an infill dwelling in a hamlet, two demolitions and replacements, and one conversion of farm buildings close to a hamlet into four dwellings.

40. The ninth permission is, like the application land, situated remote from a public road, but that property was already in residential holiday use. The officer’s report in support of the delegated decision to allow unrestricted residential use commented that the change was not expected to result in any significant change in vehicle movements. None the less, the permission was conditional on constructing reconfigured parking and turning areas at the site.

41. The permissions demonstrate a range of situations in which permissions for rural dwellings have been granted in the local area in accordance with Policy 7 of the 2016 Cornwall Local Plan for housing in the countryside. However, in my judgement this permission sits outside the ascertainable pattern of permissions in being sited remotely from a public road and having no existing residential use.

42. A particular concern that I have regarding this application is that the restriction covers the whole of the property transferred in 2004 and the applicants are seeking discharge of the restriction across the whole, even though the planning permission concerns just one stone building and its attached lean-to structure. A total discharge of the restriction would allow further building (subject to planning constraints) on the remainder of the application land.

43. The applicants’ statement of case, evidence and submissions do not mention this at all, or try to explain why the Tribunal should discharge the restriction over the whole of the land. Ms Thomson concludes her witness statement by saying that it is not the intention of the applicants to build any more on the land once their home is constructed and that they would be content with a modification to allow only the works with planning permission. From my site inspection I conclude that if the planning permission were to be implemented, taking not only the stone shed but also the attached lean-to structure out of their current use, this would inevitably create a need to erect more stables and associated buildings to replace them.

44. Moreover, there is no indication in either the permission documents, which included only floor plans and elevations for the proposed conversion, or the application for discharge, of how the proposed residential use would blend on site with use of the remaining yard area for horses. Where would a garden or sitting out area be sited? Where would cars be parked and turned? The development is said to involve installation outside the original building of a sustainable drainage system, for disposal of surface water, and a package treatment plant for the disposal of foul sewage. However, no site plan is provided to show the location of these. The proposed conversion would not sit in isolation in the stable yard and it is unrealistic to assume that residential and domestic use would be confined to the proposed building. I take this into account in considering whether the proposed development is a reasonable user of the application land.

45. In her witness statement Ms Thomson refers to the advantages of being able to live on site in order to provide a far higher standard of care for their horses and more active management of the land. And yet, as stated by the parish council, the applicants did not make their planning application on the basis of the need for a rural worker to live on site, which of course would have been harder to prove and would have given rise to an occupancy condition. But it would at least have provided the objectors with some comfort as to the nature of the proposed activities by the current and any future occupiers.

46. In conclusion on the question of whether the proposed development is a reasonable use of the application land, I do not find that the permission is in line with any ascertainable pattern of permissions in the area. The permission is itself so limited in scope and supporting detail that its existence is not sufficient to establish in this case that residential conversion of the building is reasonable. The view I formed on my inspection was that in this location residential use would not be reasonable.

47. In case I am wrong on this point, I go on to consider the further relevant questions posed by an application under ground (aa).

Does the restriction impede that use?

48. Both parties have interpreted the restriction as effectively absolute and it has not been suggested that the covenantee may only refuse consent on reasonable grounds.

49. The restriction prohibits building, or allowing to be built, “any building or structure whatsoever”. Mr Phillips submits that the restriction does not prevent the conversion of existing buildings or structures, nor control the type of use to which the application land is put. He points out that the restriction could have been drawn on wider grounds but was not. Accordingly, either the restriction does not prevent the works in the permission or its benefit is largely illusory, as described in Re Fairclough Homes [2004] EWLands LP_30_2001 where the Tribunal (George Bartlett QC, President) said at [30]:

“…By preventing development that would have an adverse effect on the persons entitled to its benefit the restriction may be said to secure practical benefits to them. But if other development having adverse effects could be carried out without breaching the covenant, these practical benefits may not be of substantial value or advantage. Whether they are of substantial value or advantage is likely to depend on the degree of probability of such other development being carried out and how bad, in comparison to the applicant’s scheme, the effects of that development would be.”

50. For the objectors, Mr Healey submits that the stable building has already been extended once in breach of covenant and the conversion will be a breach even if the new dwelling were to be confined to the footprint of the already extended structure. He submits that the verb to build is not confined to ‘build from scratch’ but is sufficiently broad to catch all the activities a builder might carry out on land to bring about a permanent change in it, including works of conversion to turn a stone stable into a residence. He says that the nouns ‘any building or structure whatsoever’ are also wide.

51. The question is whether the proposed works involve the building of any building or structure. The fact that the original building has already been extended once, and in breach of the restriction, does not alter the meaning of the restriction or its application to the structures which are currently on the land. I do not agree that the restriction prohibits all the activities a builder might carry out. However, the plans approved in the permission show that the new dwelling will have a kitchen/diner measuring 4.6 metres x 4.6 metres extending at the rear over the footprint of the current lean-to structure which is only 3.9 metres wide. This would definitely involve building of a new structure to replace the current insubstantial lean-to, and the new structure would extend beyond the existing footprint. Moreover, both parts of the new dwelling would have a pitched roof of greater height than the current monopitch roofs, which would involve the building of a roof structure.

52. For these reasons I conclude that the restriction does impede the proposed development.

Does impeding the proposed user secure to the objectors any practical benefits?

53. For the objectors Mr Healey submits that “practical benefits” has a wide meaning, as established in Gilbert v Spoor [1983] Ch.27. It is a practical benefit to be able to prevent new dwellings and, more generally, unwanted structures from being constructed on land embedded within the farm and adjacent to the retained land of the objectors.

54. There is no suggestion in the objections that discharge of the covenant would result in the destruction or significant alteration of a beautiful vista or landscape but, in commenting on visual amenity, the objectors say that the application land is visible from the top floor of their house, the land around their house and the track between their farm buildings and beyond. Mr Phillips points out that the application land is physically distant from the farmhouse; there is no line of sight between the farmhouse and the building with the permission; the view of the building is not easily accessible from the farm in the normal course of daily life, nor one that would be adversely affected by implementation of the permission.

55. When I inspected, during a period of Covid-19 precautions, it was requested that I did not enter the farmhouse. I am therefore unable to comment on views from the farmhouse, but I can comment that the stable yard, and in particular the shed with permission for conversion, was barely visible from the fields behind the farmhouse and yard. It is, of course, highly visible as one moves down the track between the stable yard and cottage.

56. The objectors point out the rural character of the area, as a farm and equine space, and claim that there would be more noise and disruption arising from domestic use of the stable yard than its current use for keeping horses. There would be visitors and deliveries, in addition to the coming and going of the applicants, creating an increase in traffic, not a reduction as suggested by the applicants. The application land is said to be particularly close to the area of land where Mr Collins houses his prize chickens in the summer months, and he would therefore see the proposed dwelling daily during that period.

57. I consider that the effect of the restriction in limiting traffic movements does have weight as a practical benefit. The fact that there is already domestic use very close to the stable yard, at the cottage, has served to illustrate to the objectors the disadvantage of having residential use beyond their control within the farm. Mr Collins explains in his witness statement that the cottage has limited parking, restricted to the track, and historically he has had legal disputes with the previous owner. He feels strongly that he must object to modification of the restriction over the application land in order to protect himself from the adverse consequences of additional residential use and further potential causes of dispute.

58. I consider from my own observations that the constrained nature of the location, effectively a pinch point on the track, creates considerable potential for disputes over parking and access. The cottage has parking only on the track and the stable yard has only limited scope for parking and turning. The two properties are separated by the narrow track which must be kept clear for access. Mr Collins points out that although the verge to the track outside the stable yard remains in his ownership, the applicants have erected a portable garage there. I observed this structure during my inspection. This is not a breach of the restriction, because it is not on the application land, but a good example of an action by the applicants which is a potential cause of dispute and would require some enforcement action by Mr Collins to effect removal.

59. The permission plans show the residential conversion fronting on to the track and its only access would be from a door opening directly onto the track where it is already narrow. I am very surprised that this was considered a suitable design for planning permission. I have not been made aware of any comments made by the owners of the cottage during the planning process, which is an encouraging sign of good neighbourliness. Tolerance and cooperation cannot be guaranteed from any future owners of the cottage, or of the application land, and in my view the objectors are right to be concerned about potential future disputes affecting their enjoyment of the farm.

60. I consider that there are clear practical benefits in the preservation of the rural character of the area as a farm and equine space, with minimum potential conflict between users of the objectors’ track. Land belonging to the applicants is surrounded on three sides by agricultural land belonging to the objectors and their son and the track on the fourth side provides the access to the son’s agricultural land. The ability to prevent additional building on the application land, and thereby in practice to avoid the adverse consequences of intensification and change of use, is a particularly important practical benefit of the restriction.

Are the practical benefits of substantial advantage?

61. Referring to the decision in Re Beardsley’s Application [1973] 25 P & CR 233, Mr Healey submits that the ability to protect peace and quiet is a benefit of substantial value and advantage. Moreover, control over any possible development on a farm as a whole is a benefit of substantial advantage.

62. The applicants consider that if there is a practical benefit to the restriction it cannot be substantial as consent has previously been given (although not in writing) for certain additional buildings associated with use of the application land for horses. However, it is disputed by the objectors that they gave permission for additional structures to be built. In his witness statement Mr Collins explained that in some cases he was either not consulted or, for the new pole barn in particular, was ignored when he declined to give permission. As with the portable garage on the objectors’ grass verge, these are examples of actions taken by the applicants which necessitate some reaction by the objectors in order to remedy the situation.

63. The applicants maintain that as the restriction provides for written permission to be given for further buildings or structures, this must have been envisaged as a likely outcome. Mr Healey submits that the inclusion within the restriction of a provision for approval to be granted is not evidence that it is a less than substantial advantage.

64. The applicants also state that prior to their purchase of the application land the objectors told them they had attempted to get planning permission to undertake a development on that land and there can therefore be no substantial benefit to the prevention of conversion to a dwelling. Mr Collins has explained that he once had some drawings prepared by his local firm of auctioneers, at a time when many farmers in the area were considering similar schemes. He maintains that he told the applicants about this in the context of explaining the reason for imposing the restriction.

65. Mr Healey submits that the first objector was only prepared to sell in reliance on the fact that he would have the benefit of the restriction, which is evidence that it was considered to be a substantial advantage. In Re Collins’ Application [1975] 30 P&CR 527, an increase in density of housing, which was restricted by a building scheme, would not result in any depreciation to the market value of the objectors’ houses but the restriction was held by Douglas Frank QC, President, to remain a substantial advantage.

66. In my judgement, having inspected the application land and the farm, the advantage to the objectors of being able to prevent intensification of use of the land, and to limit opportunities for conflict, is clearly a benefit of substantial advantage.

Is impeding the reasonable user contrary to public interest?

67. I have stated previously that I do not consider the proposed conversion of the stone shed to be a reasonable user of the application land, but the applicants relied on this limb of ground (aa) and I will consider this question in case I am wrong.

68. Mr Healey submits that to succeed under this limb the applicants would need first to identify the relevant public interest and then to persuade the Tribunal that that interest was harmed by these buildings remaining as stables.

69. Mr Phillips submits that the buildings (presumably the stone shed and attached lean-to) are not currently of any practical use as stables and that the Tribunal can rely on the terminology in the permission which refers to a redundant stone farm building. From my inspection I question the redundancy of the stone shed and can confirm that the lean-to shed had a horse tied up inside and other parts appearing to be in use for associated horse care activities.

70. Mr Phillips submits that prevention of the works would be contrary to the public interest because, whilst planning permission is not determinative, Cornwall Council granted the permission and are best placed to determine the housing needs of the local area. He says that plainly the retention of a redundant stone building, and the associated inability to turn the same into housing accommodation without the need to build on any virgin land, would be contrary to the public interest.

71. Mr Phillips drew attention to the principle stated in Re Lloyd’s and Lloyd’s Application (1993) 66 P&CR 112 - where there is an established need for the type of construction that would be facilitated by the discharge of the covenant and the development is well suited to meeting that need, the public interest test can be met. However, Mr Healey points out that that case involved an extreme situation where there was a ‘desperate’ need in the locality for the development of the type of care home proposed and specialist expert medical evidence was called in support of the application. This case is entirely different.

72. This would be a single private dwelling on a modest scale that would make a tiny difference to the housing needs of the area. There is no significant public interest in the conversion and I am satisfied that impeding it is not contrary to the public interest.

The Tribunal’s discretion

73. S.84(1)(B) requires the Tribunal to take into account the development plan and any declared or ascertainable pattern for the grant or refusal of planning permissions in the relevant area. I have previously determined that I do not find the permission is in line with any ascertainable pattern of permissions in the area.

74. The Tribunal is also required to take into account the period at which and context in which restriction was created or imposed and any other material circumstances. I acknowledge that in 2004, when the restriction was imposed, the planning policy framework for the area would have been different and that the importance of housing in policy making is now very clear. However, the applicants are the original covenantors, the first objector is the original covenantee, only 16 years have elapsed since the giving of the covenant, and there has been no relevant change in circumstances at the farm apart from the obtaining of planning permission.

75. Even if one of the grounds under section 84(1) had been satisfied, the factors I have identified would have given rise to a real question over the exercise of the Tribunal’s discretion. As I do not find that ground (aa) has been satisfied, it is not necessary for me to resolve that question.

76. The application fails because the proposed user is not reasonable and, even it is was, in impeding that user the restriction secures a practical benefit of substantial advantage to the objectors and is not contrary to the public interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV |

|

|

Dated: |

11 December 2020 |

APPENDIX 1