Introduction

1. This appeal is brought with the permission of the First-tier Tribunal (“the FTT”) from its decision on a reference from HM Land Registry. The vicar of St James’ Church in the village of Saul applied to HM Land Registry in 2018 for a vehicular right of way, for the benefit of the church, over land belonging to the neighbouring property. The neighbouring owners objected and the matter was referred to the FTT pursuant to section 73(7) of the Land Registration Act 2002, and the FTT directed the registrar to register the easement.

2. The appellants are Mr and Mrs Hughes, the neighbouring owners; the respondent is the vicar, the Incumbent of the Benefice of Frampton-on-Severn, Arlingham, Saul, Fretherne and Framilode. The incumbent has the status of a corporation and made the application in their capacity as the freeholder of the church. Because the incumbent was the applicant in the FTT, and the appellants here were the respondents there, I refer to them as the incumbent and the appellants respectively.

3. The appellants’ property is a former school site next to the church, where they have built their home, and the easement sought by the incumbent is over a track or drive which gives access to the appellants’ home from the public highway. The incumbent claims to have acquired by prescription an easement along the track for vehicles to pass between the highway and a grassed area belonging to the church, where they can park, on the basis of many years’ use by successive incumbents and their visitors.

4. I heard the appeal by remote video platform on 27 July 2021; counsel for the appellants was Mr Jonathan Wills, for the respondents Mr Timothy Calland, and I am grateful to them both for their helpful arguments and for their patience with my questions. The appeal was conducted as a review of the decision of the FTT; there was no re-hearing of the evidence.

The factual background

5. The legal title to the church in the village of Saul is vested in the incumbent, which means that it is held by whoever is the vicar for the time being. Next to the churchyard is a plot of land given in 1856 to the incumbent and churchwardens for a school. The incumbent and churchwardens held the site on trust, until 2001 for educational purposes, and from 2001 onwards after the school closed on the trusts created by the Reverter of Sites legislation. In 2011 the incumbent and churchwardens made an application to register title to the school site and to the track that leads to it from the highway. The school site and track were registered as a single title, which the incumbent and churchwardens then sold in 2012 to Mr and Mrs West, who sold it in 2015 to the appellants.

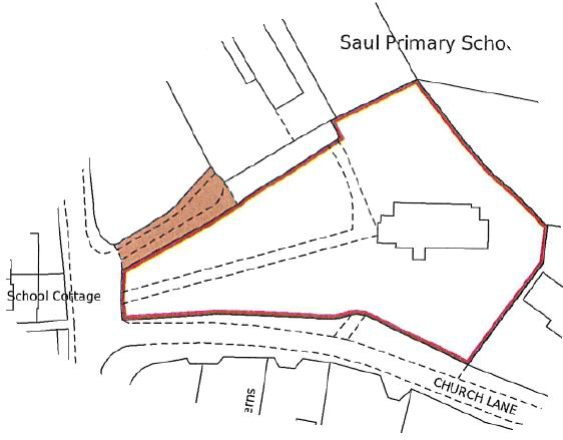

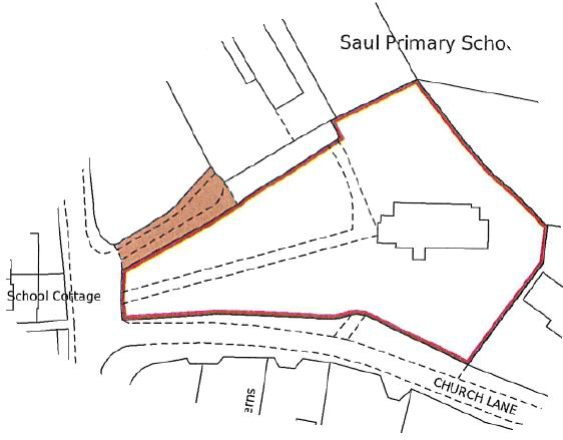

6. The decision of the FTT in this reference is distinguished by its inclusion of plans which made the layout of the land concerned and the relationship of the different parcels crystal clear, and I am most grateful to the judge. I have adapted one of the plans from the FTT’s decision; it shows the church’s land registered under title number GR338787, edged red, and the grassy patch which is also in the church’s ownership, registered under title number GR348550, hatched green. The school site is indicated, and the track is shaded brown.

7. In 2018 the incumbent applied to HM Land Registry for the registration of an easement acquired by prescription over the track, for the benefit of the land registered under title number GR338787. It was claimed that the track had been used by successive incumbents and their visitors - for example, visiting ministers, people tending graves, and the funeral director - for more than twenty years, for vehicular access to the grassy area where vehicles parked in order to gain access to the churchyard and church through the north gate.

The law: what did the incumbent have to prove?

8. There are three ways to claim an easement by prescription in the law of England and Wales. A claimant may establish use from “time immemorial”, that is from the limit of legal memory in 1189; or the claimant may meet the requirements set out in the Prescription Act 1832; or the claimant may satisfy the requirements of the doctrine of lost modern grant. This legal jungle will become a clear highway if the recommendations of the Law Commission’s 2011 Report Making Land Work, Law Com No 327, are enacted, but for now the jungle remains. Because the track cannot be shown to have been in use since 1189, and because it has not been used since 2016, only the doctrine of lost modern grant was open to the incumbent in this reference.

9. In its origins the doctrine of lost modern grant depended upon a fiction, whereby the court found that the facts were such that there must have been an express grant of an easement in the past, which has now been lost. In Tehidy Minerals Ltd v Norman [171] 2 QB 258 Buckley LJ said:

“… where there has been upwards of twenty years’ uninterrupted enjoyment of an easement, such enjoyment having the necessary qualities to fulfil the requirements of prescription, then unless, for some reason such as incapacity on the part of the person or persons who might at some time before the commencement of the twenty-year period have made a grant, the existence of such a grant is impossible, the law will adopt a legal fiction that such a grant was made, in spite of any direct evidence that no such grant was in fact made.”

10. I shall have to say more in due course about the authorities relating to the sort of use that has “the necessary qualities to fulfil the requirements of prescription”.

The FTT’s decision

11. The incumbent was successful before the FTT.

12. The FTT heard evidence from witnesses for the incumbent, including Mr Wood, who has lived in Saul and attended the church for 60 years and is a funeral director, and Rev Spargo who was churchwarden from 1996 to 2002, curate from 2006 and the incumbent from 2010 to 2016. They gave evidence of their own vehicular use of the track and that of other visitors to the church over many years. The appellants and their witnesses on the other hand gave evidence the track had been used for access to the school until it closed, and since then for the maintenance of land to the north-west of the track known as The Pound. That use stopped when the Wests purchased, and thereafter it had been used only with the Wests’ permission. The FTT accepted the evidence of the incumbent’s witnesses and found that the claim to a prescriptive easement was made out.

13. The FTT had to deal with three other legal points which are not appealed, and which I can summarise briefly for the sake of completeness. First, it was argued for Mr and Mrs Hughes that as the incumbent had been an owner of the school site until it was sold in 2012, no easement could have arisen because of the doctrine of unity of seisin (a person cannot have an easement over their own land). That argument failed because the school site was vested in the incumbent and churchwardens, whereas the freehold of the churchyard is vested in the incumbent alone; there was no unity of seisin. I asked Mr Wills and Mr Calland to explain to me how prescription would work in these circumstances, and why the use of the track by the incumbent (for example Ms Spargo herself) would not be attributable to their right to use it as freeholder. The answer is that the trustees of the school site were entitled to use it only in accordance with the trusts on which it was held, which would not have permitted the trustees (including the incumbent) to drive along the track in order to reach the grassy patch nor to permit the incumbent or anyone else to do so. There is some limited authority to the effect that an incumbent in one capacity may prescribe against himself in another (Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England v Kino (1880) 14 Ch D 213); the point is not in issue on this appeal and this decision is not to be taken as authority on this point.

14. Second, it was argued that vehicular use of the drive was a criminal offence because the drive is also a public footpath. That argument failed.

15. Third, it was argued that the easement if it came into being by prescription could not have bound the appellants because it was not registered when they purchased and therefore, on registration, they took free of it (section 29 of the Land Registration Act 2002). The FTT found that the easement bound the appellants as an overriding interest because it had been used during the 12 months before they purchased in 2015, even though (as the FTT accepted) the appellants did not know about it and it was not apparent on reasonably careful inspection (paragraph 3 of Schedule 3 to the Land Registration Act 2002).

16. The FTT gave permission to appeal on two grounds.

Ground 1: In light of the Tribunal’s finding that the Incumbent’s use was occasional, the Tribunal was bound to find that the use was not sufficient to give rise to a right of way by lost modern grant.

17. For the appellants it is argued that the finding of fact made by the FTT about the use of the track was such that the incumbent could not have succeeded.

18. That is because the use claimed as the basis of a prescriptive easement must be of sufficient intensity or frequency to indicate that a right is being asserted. Gale on Easements, 21st edition, says at paragraph 4-169:

“The enjoyment must be definite and sufficiently continuous in its character….In those easements which require the repeated acts of man for their enjoyment, as rights of way, it would appear to be sufficient if the user is of such a nature, and takes place at such intervals, as to afford an indication to the owner of the servient tenement that a right is claimed against him—an indication that would not be afforded by a mere accidental or occasional exercise. On the other hand, the evidence may disclose a casual use, dependent for its continuance upon the tolerance and good nature of the servient owner, and not such as to put him on notice that a right is being asserted.

19. At paragraph 226 of its decision the FTT said:

“I have concluded that the evidence shows, on the balance of probabilities, that occasional use has been made by the church by the Incumbent from time to time and its visitors of the tarmac path owned by Mr and Mrs Hughes since at least 1992, being 20 years before 2012, and into 2015.”

20. What the appellants argued before the FTT was that whilst there had been some use of the track in the past for access to the grassy patch, it had been merely occasional and therefore insufficient to found a claim in prescription. And occasional use, says Mr Wills, is precisely what the FTT found. Occasional use is not enough.

21. Mr Wills cautions against reasoning backwards from the fact that the judge found the requirements for prescription to have been made out and therefore concluding that the level of use was sufficient. Having found that it was only occasional, he argues, the judge should have stopped there.

22. In response Mr Calland points to paragraph 218 where the FTT said this:

“The evidence of Mr Wood, who could speak to events from before 2012, and of Rev Spargo, whose knowledge was more recent, is of particular assistance. I accept their evidence that, as a matter of routine dating back many years the servient land was used as follows:

218.1 To provide access for clergy attending Sunday services to the car parking on the grassed area and access to the church through the north gate;

218.2 To provide access for visitors attending services and also weddings, christening, funerals, community meetings and events.

218.3 Family members tending graves.”

23. Mr Calland reads “as a matter of routine” to indicate regular and more than occasional use. Mr Wills says it means “without fanfare, and without being able to be particularised as to date”, and notes that at 256 the judge said “the use of the right of way was never frequent”.

24. Crucially, Mr Calland argues, the judge accepted the evidence of Mr Wood and Rev Spargo. Mr Wood said that he and his family had attended the church for over 60 years and that throughout the time he has known the church the track has been used by vehicles to get to and to park on the grassy patch. It is the disabled access to the church. He has “often” used it to park for a funeral and access is used “regularly”. Rev Spargo led a music group at a weekly service between 1996 and 2002 and used to drive up the track and park on the grassy patch so get as close to the church as possible since she had to carry instruments including a cello and a drum kit. Later she was curate and then incumbent, and she said that between 2006 and 2016 she used the grassy patch for parking (and therefore the track for access) 3 or 4 times a month. She said that previous incumbents used the track and parked on the grassy patch on a weekly basis, and that other worshippers and visitors would also use it. A reader who was wheelchair-bound used to park there when leading services because it was the only way she could get to the church unaided. The use of the track and the parking was “not minimal”.

Conclusion on ground 1

25. The requirement that the use that is relied upon to give rise to a prescriptive easement be more than “occasional” is not an absolute one - nor could it be since the term is imprecise and context-dependent. Weekly use, for example, might be regarded as occasional in some contexts and frequent in others. The point of the requirement is not to impose an arbitrary standard of frequency but to require sufficient use to put the servient owner on notice that a right is being asserted and that he or she needs to take action.

26. At paragraph 230 the judge found that the use made of the track by the incumbent and their visitors was sufficient to put the servient owner on notice as required. To point to that finding as the crucial one is not to reason backwards; the point is that the judge made the findings necessary to establish prescriptive use.

27. In addition, I accept Mr Calland’s arguments about the evidence that the judge accepted, and about the meaning of “as a matter of routine”. The indications of frequency given by Rev Spargo indicate the meaning of “as a matter of routine” in the judge’s summary of the evidence at paragraph 218. He did not suggest that he accepted part only of her evidence or that he rejected any of it; true, at paragraph 225 he said that more detailed witness statements would have been helpful, but despite that lack of detail (in particular the lack of dates) he accepted the evidence of both these witnesses and did not qualify that acceptance. He described that evidence at paragraph 226 as being of “occasional” use, but the use that Mr Wood and Rev Spargo gave was not of “occasional” use in the sense that that word is used in the paragraph quoted from Gale, nor in the sense used by Mr Wills in his arguments for the appellants. When we look at the evidence that the judge is summarising it is clearly not a “casual” use of the kind that Gale says is insufficient. Rev Spargo’s evidence of weekly use, and of her own use three or four times a month, makes that abundantly clear.

28. Accordingly the first ground of appeal fails.

Ground 2: In the alternative to ground (i), if it was not inevitable that occasional use would be insufficient, the Tribunal erred in making no finding as to whether the occasional use was enough to carry to the mind of a reasonable person who is in possession of the servient tenement, the fact that a continuous right to enjoyment is being asserted.

29. Mr Wills refers to the parties’ agreement that the test is that set out in Mills v Silver [1971] Ch 281: the use must be

“enough to carry to the mind of a reasonable person who is in possession of the servient tenement, the fact that a continuous right to enjoyment is being asserted.”

30. Accordingly, if the FTT had indeed found that a prescriptive easement had arisen without addressing the question whether the use of track was sufficient to make a reasonable servient owner aware that a right was being asserted, as the authorities put it, then that would be a serious flaw in the reasoning. However, the FTT said at paragraph 230 of its decision:

“In the context of a country church serving a small congregation, it is my judgment that enough had been done by the Applicant and its lawful visitors to suggest to a reasonable servient owner that a right was being exercised and ought to be resisted if not accepted.”

31. That paragraph is a complete answer to what is set out under ground 2 in the Grounds of Appeal.

32. However, at the hearing, however, Mr Wills developed ground 2 further. He explained that what the FTT failed to make a finding on was his argument that in the light of what was said in statutory declarations made in 2011 when title to the school site was registered, and in light of what was said on behalf of the incumbent and churchwardens when the land was sold to Mr and Mrs West in 2012, Mr and Mrs West will have been well aware that no right was claimed over the track and therefore could not possibly have been put on notice, after their purchase, that the use of the track was a prescriptive use and would be relied upon to claim a legal easement.

33. In 2011, in support of the application made by the incumbent and churchwarden to register the title, statutory declarations were made by a former governor of the school and by the advisor to the Diocesan Board of Education:

“I have never heard of any person or persons or body having or claiming any title to or interest in the said land”

34. In the vendor’s Property Information Form in 2012, in answer to “Are there any formal or informal arrangements which someone else has over the property?”, the “no” box was ticked.

35. What all that meant, and what it would have told Mr and Mrs West, was the subject of some argument at the hearing. I do not need to resolve any of that because what the reasonable servient owner in the position of the Wests would have thought is irrelevant. At paragraph 18 above I quoted paragraph 226 of the FTT’s judgement which says that twenty years’ use had been completed before 2012. The Wests purchased in July 2012 and therefore after prescription was complete.

36. Mr Wills then argued that “before 2012” meant before July 2012 when the Wests completed their purchase, and that there was a period before then where 20 years had not yet been clocked up, during which the incumbent and churchwardens having made that statement in the Property Information Form must have been well aware that no right was being claimed by the church. Accordingly prescription was interrupted before July.

37. That argument appears to rely upon the servient owner (being three persons, the incumbent and churchwardens) being made aware by their own statement that the dominant owner (the incumbent, who was at the same time the freeholder of the church) did not intend to claim an easement. Whether that is either realistic or legally possible is irrelevant because it flies in the face of the plain words “before 2012” in the decision, which are consistent with Mr Wood’s evidence (which the judge expressly accepted) of use for well over 20 years.

38. It is of course obvious that in 2011 and 2012 the church (whether we think of it is a group of people, or as the incumbent, or as the vicar and churchwardens) had no intention of claiming an easement over the track; if the church had wanted an easement at that stage then the incumbent and churchwardens could have granted an easement to the incumbent before they sold or as part of the same transaction. But there is nothing in law to prevent the incumbent from claiming prescriptive use now, despite the fact that successive incumbents were unaware that their use of the track would later enable them to do so and apparently had no intention of doing so. That makes no difference to whether or not their use of the track was sufficient to meet the requirements of prescription.

39. It is clear, on the facts found by the judge, that prescription was completed before the first moment of 2012. Accordingly I do not need to consider any further Mr Will’s expansion of ground 2 at the hearing, nor whether I should grant leave to amend the grounds so as to add that argument, since it is doomed to failure.

Conclusion

40. The appeal is dismissed and the FTT’s direction to the registrar takes effect.

Judge Elizabeth Cooke

4 August 2021