Introduction

1. This appeal arises out of a boundary dispute between the registered proprietors of two parcels of land, originally part of a single Cumbrian farmstead, which were conveyed separately, the first in 1986, the second in 1991. The 1986 conveyancing was of poor quality, using an inadequate plan to show the intended boundary across an open yard separating the farmhouse retained by the vendor and a barn conveyed to the purchaser. When the farmhouse itself was sold in 1991 the boundary through the yard was shown in a different place on the conveyance plan. A diligent comparison of the title plans would have given the impression that an orphaned parcel, shown neither on the first plan nor on the second, lay between the two titles. For many years the discrepancy was unnoticed and of no consequence but later owners have fallen out and the orphaned parcel has become their battle ground.

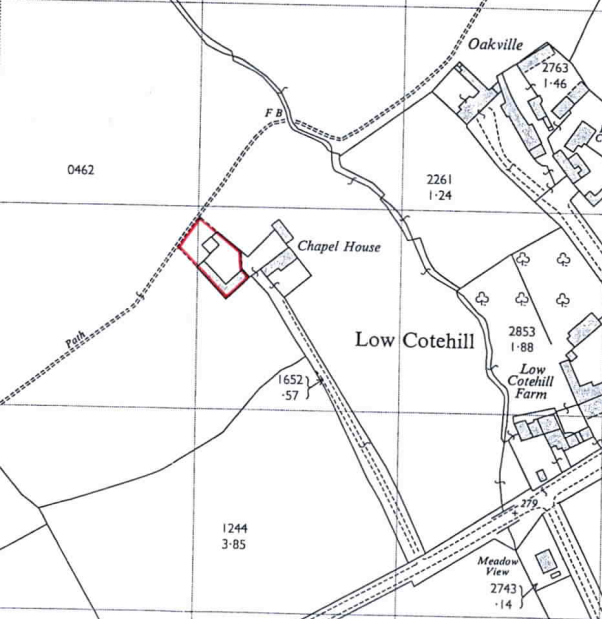

2. Those later owners are the appellant, Mrs Scott, the registered proprietor of Chapel House, Low Cotehill, Cumbria, and her neighbours, the respondents, Mr and Mrs Martin, the registered proprietors of Windhover Barn (formerly Chapel House Barn). I will refer to their respective properties as “the House” and “the Barn”.

3. In 2015 Mr and Mrs Martin obtained a transfer, purportedly of the orphaned parcel, from the original 1986 and 1991 vendors, Mr and Mrs Field. Their application for first registration was objected to by Mrs Scott, who claims that the orphaned parcel is illusory and had been included in the 1991 conveyance of the House to her former husband.

4. In a decision given on 23 March 2020 the First Tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) (the FTT) dismissed Mrs Scott’s objections and directed the Chief Land Registrar to give effect to Mr and Mrs Martin’s application for first registration on the basis of the 2015 transfer. Permission to appeal the FTT’s decision was granted by this Tribunal.

5. At the hearing of the appeal, which took place by remote digital platform, the parties were represented as they had been before the FTT, with Mr William Hanbury appearing for the appellant and Mr Richard Oughton for the respondents. I am grateful to both counsel for their helpful submissions.

Issues on the appeal

6. The appeal and a cross appeal by the respondents raise three issues:

(1) Did the 1991 Conveyance convey the disputed land to the appellant’s predecessor in title, Mr Scott, as purchaser of the House? The FTT held that it did not, and the appellant challenges that part of its decision.

(2) Did the 1986 Conveyance convey the disputed land to the respondents’ predecessors in title as purchasers of the Barn? The FTT decided that it did not, but the respondents challenge that conclusion by their cross-appeal.

(3) Did the 2015 Transfer convey the disputed land to the respondents? The FTT held that it did, and the appellant also challenges that conclusion.

The conveyancing history

7. Low Cotehill is an outlying settlement about half a mile to the east of the village of Cotehill and about six miles south of Carlisle. The House, the Barn, and a number of other former agricultural buildings are on the fringe of the settlement, arranged around three sides of a yard at the end of a long track with fields on either side. Before 1986 the whole group was owned by Mr and Mrs Field.

8. The general layout of the House and Barn are shown on the orientation plan appended to this decision. The House stands on the right side of the track where it opens into the yard. The Barn stands to the left, on the opposite side of the track. The Barn is in an “L” shape, enclosing the south-western corner of the yard. There are buildings on three sides of the yard with the rest of its perimeter formed by a low stone wall.

The 1986 Conveyance of the Barn

9. Mr and Mrs Field purchased the House and its various outbuildings, including the Barn, in 1976. On 24 October 1986 they conveyed the Barn to Mr Dubieniec and Ms Mottram, who subsequently converted it to residential use.

10. The 1986 Conveyance described the land conveyed as:

“All that piece of land situated at Chapel House, Low Cotehill… with the Barn erected thereon or on some part thereof and known as Chapel House Barn, Low Cotehill aforesaid which said property is for the purpose of identification only shown edged red on the attached plan.”

11. The land shown edged red on the 1986 Conveyance plan comprises the Barn and a portion of the yard marked with a thick black line on an ordnance survey plan. The parcel is approximately rectangular with straight boundaries on three sides. On the north-eastern side, abutting the House and the remainder of the yard, the boundary is not straight but is delineated on the plan by a line between 4 points, marked A, B, C and D. The boundary between points A and B runs along part of the low wall surrounding the yard and separating it from an adjoining enclosure with Point A at the northern end of the wall. Point B is shown on the plan as being approximately six or eight feet before the southern end of the wall. This wall is stated in the 1986 Conveyance to be a party wall. The boundary between points B and C is not represented by any physical feature but crosses diagonally over the open yard towards the north-eastern corner of the Barn. When the boundary reaches point C it turns again to follow a course parallel to the flank wall of the Barn to point D. Because of the thickness of the line on the plan it is impossible to tell whether the boundary between points C and D runs along the face of the flank wall or at some distance from it.

12. By clause 3 of the 1986 Conveyance the purchasers covenanted with the vendor that they would erect and maintain two structures on the boundary. The first was to be a gate between the points marked B and C on the plan; the second, a fence or a wall between the points marked C and D. The purchasers also covenanted to use the Barn as a private dwelling house.

13. In 1997 the Barn was sold again, this time to Mr Ashley and Ms Berry, and the title was registered for the first time. The third and final sale of the Barn was to the respondents, on 11 June 1999.

The 1991 Conveyance of the House

14. Before the respondents acquired the Barn, Mr and Mrs Field had sold the House to Mr Scott by a conveyance dated 27 June 1991. Title to the House then became registered and was acquired by the appellant on 3 November 2003.

15. The 1991 Conveyance begins with an acknowledgement of receipt of the purchase price paid for “the land and detached house known as Chapel House, Low Cotehill, Carlisle, Cumbria (“the Property”)”. By clause 4(b) the Property is said to be subject to the rights granted by the 1986 Conveyance.

16. The Property is further described in clause 3, where it is said to be “delineated for the purpose of identification only [on] the plan attached hereto and is thereon edged red.” The plan to the 1991 Conveyance is again based on the ordnance survey and again shows boundaries marked by thick lines. The whole length of the wall which the 1986 Conveyance had designated between points A and B as a party wall is shown marked by a heavy red line. The boundary then crosses the yard not to the point marked C on the 1986 Conveyance plan but distinctly towards the point marked D on that plan. The line is thick enough on the copy I was shown to span almost the whole of the space between the corner of the gable wall of the Barn and the closest corner of the House and gives no precise indication of where the boundary is intended to be.

17. The material in evidence before the FTT included sales particulars prepared by Smiths Gore, the agents who acted for Mr and Mrs Field in 1991, and a report on purchase prepared by solicitors acting for Mr Scott, the purchaser. The sales particulars contained a plan which appears to have been used as the basis of the 1991 Conveyance plan, and on which the boundaries of the land for sale are shown by a narrower line. Nothing in the particulars suggests that the vendors of the “desirable country house with grounds” intended to retain any part of it after the sale.

18. The solicitors’ report on purchase also includes a copy of the Smiths Gore plan on which three points on the boundary have been marked as A, B and C. The report emphasises that the plan is for identification only and that it is essential that the purchaser carefully check the actual boundaries in order to ascertain that the plan is accurate. The report continues:

“The deeds make provision regarding ownership of the walls dividing the property from the adjoining house known as Chapel House Barn and as between the points marked A-B. These are stated to be party walls …. The remaining part of the boundary between the points marked B and C are walls or fences owned by the adjoining property who are responsible for their maintenance. The deeds do not make provision for ownership of any of the other boundary walls.”

The point marked A on the plan attached to the 1991 report on purchase is in the same location as the point marked A on the 1986 Conveyance plan, at the northern end of the party wall. But the points marked B and C on the report plan are not the same points as are marked B and C on the Conveyance plan. In fact, point C on the report plan appears to be in the same location as point D on the 1986 Conveyance plan, at the southern end of the gable wall of the Barn. There is no reference in the report to a point marked D

19. The other matter of note concerning the 1991 report is that the writer was mistaken in describing the boundary between the points marked B and C as being marked by walls or fences. The 1986 Conveyance did indeed include a covenant by the purchasers to erect gates and walls or fences on the open boundary, but that obligation had never been fulfilled and in 1991 the boundary across the yard remained unmarked by any physical feature.

The 2015 Transfer

20. The boundary between the Barn and the House first became contentious in about 2006. The respondents were eventually advised that a parcel of land appeared not to have been included in either the 1986 or the 1991 Conveyances. Although the area in question was not large, it was not unimportant since it ran alongside the gable wall of the Barn where it adjoined the yard. Utility meters serving the Barn had been installed on that wall as part of its conversion to residential use after 1986, and the 1986 Conveyance granted no right of access to these, or for any repairs which might be required to the gable end wall itself.

21. In 2015 the respondents agreed to acquire this parcel of land from Mr and Mrs Field, on the assumption that it had remained in their ownership after 1986 and had not been conveyed in 1991. Clause 2 of the 2015 Transfer described the property transferred in the following terms:

“The remaining land at Windhover Barn below Cotehill, Carlisle more particularly described in a Conveyance dated 24 October 1986 and made between [Mr and Mrs Field and the 1986 purchasers].

The FTT’s decision

22. The FTT noted that it was common ground between the parties that the plans filed with the registered titles of the Barn and the House could not be used to determine the location of the boundaries and that it was the pre-registration documents which must be examined for that purpose. A plan prepared in 2011 by the respondents’ surveyors, Hyde Harrington, interpreted the conveyance plans as each excluding an area of land between the boundaries where they cross the yard. This area was the subject of the disputed 2015 Transfer. The disputed land is of an irregular shape but may be as much as 10 feet wide at its widest point and perhaps 30 feet long at its longest.

23. The issue for the FTT was whether the disputed parcel of land shown on the Hyde Harrington plan was included in the 1986 or the 1991 Conveyances or the 2015 Transfer.

24. It was agreed that the verbal description of the land in the 1986 Conveyance was so vague or ambiguous that the plan and other material would have to be considered in locating the boundary where it crossed the yard. Point A was clearly the northern end of the party wall and was not in issue. Point B was contentious: the respondents said it was at the opposite end of the party wall from A, where the wall turned through 90 degrees; the appellant argued that it was at some distance north of that point. As to this dispute, and as to the location of the boundary between points C and D, the FTT reached the following conclusions:

“As to point B, I see no inherent reason why a legal boundary should be preferred at the right angle of a wall, and the 1986 Conveyance Plan, poor though it is, indicates point B as being to the north of the turn in the stone wall. It is also clear from the plan that points C-D run along the gable wall, north to south, whereas the [respondents’] C-D runs east to west.”

The FTT therefore concluded that the disputed parcel of land was not included in the 1986 Conveyance.

25. As for 1991 Conveyance, again the verbal description was ambiguous and the plan and any other appropriate evidence could be used to identify the land being conveyed. The FTT found that the plan to the 1991 Conveyance was a copy of the Smiths Gore plan used in the sales particulars. On the plan “there is a diagonal line, marked A-B running from the 45-degree angle of the stone wall to a point at the side of the entrance track but away from the gable wall of the Barn”. The FTT then quoted what had been said in the report on purchase about the reliability of the plan and about the presence of boundary features (see paragraph 18 above) before continuing:

“The points, A, B and C on the supplied plan are the stone wall (A-B) and the diagonal line mentioned above (B-C). Clearly the writer had seen a copy of the 1986 Conveyance when preparing the report but was unaware that no walls or fences had been constructed as required by clauses 3(A) and (C) of the 1986 Conveyance. I consider that I can have regard to the report in construing the 1991 Conveyance for the extent that it very likely reflects replies to preliminary enquiries provided by Mr and Mrs Field’s solicitors see: Toplis v Green [1992] [Lexis citation 3514].”

26. The FTT dismissed a suggestion that practical difficulties of manoeuvring within the yard assisted in locating the boundary. It finally considered the appellant’s argument that in 1991 Mr & Mrs Field must be assumed to have intended to sell the whole of their property and not to retain a narrow strip along the boundary, as follows:

“The second matter relied on by the [appellant] is that if the Disputed Land was not included in the 1991 Conveyance this would have left such land in the ownership of Mr and Mrs Field for no obvious reason, so that it must have been intended that such land was included. One must be cautious however, in attributing to parties a common intention which they might not have had concerning an issue that was not apparently raised or addressed at the time of 1991 Conveyance. The issue is not how they would have dealt with matters had it been considered but what proper inferences can be made about their objective intentions from the available material to which regard can properly be had. I do not consider that the retention of orphan land overrides the plan which was used in respect of the transaction and the fact that the shape of the boundary in issue would have differed considerably on that plan had it been intended the Disputed Land would be included.”

For those reasons the FTT found that the disputed land was not included in the 1991 Conveyance either.

27. The FTT then considered the effect of the 2015 Transfer. The appellant had argued that the description of the property (see paragraph 21 above) was too vague to be capable of transferring any land. But the issue over the boundary formed part of the background to the transfer and on that basis the FTT was satisfied that the description was adequate to identify the strip of land between the two titles. It therefore found that the disputed land had been transferred to the respondents by the 2015 Transfer and directed the Chief Land Registrar to give effect to their application for first registration as if the appellant’s objection had not been made. It declined an invitation to determine the boundary between the properties.

Relevant principles

28. There was no disagreement between counsel over the relevant principles of interpretation. Mr Hanbury referred to HM Land Registry’s Practice Guide 40, Supplement 3 (at section 4), which provides a clear summary:

“Case law establishes that the position of the legal boundary will depend on the terms of the pre-registration conveyance or the transfer as a whole, including, of course, the plan. If the plan is insufficiently clear for the reasonable lay person to determine the position of the boundary, the court can refer to extrinsic evidence and in particular to the physical features on the ground at the time.

This is the case whether or not the plan is “for the purposes of identification only”. The question for the court is: what would the reasonable lay person think they were buying? Evidence of the parties’ subjective intentions, beliefs and assumptions are irrelevant.”

29. In Alan Wibberley Building Ltd v Insley [1988] 1 WLR 894, 896 A-C, Lord Hoffmann referred to some of the problems commonly encountered in interpreting conveyances of unregistered land and which feature in this appeal:

“The parcels may refer to a plan attached to the conveyance, but this is usually said to be for the purposes of identification only. It cannot therefore be relied upon as delineating the precise boundaries and in any case the scale is often so small and the lines marking the boundaries so thick as to be useless for any purpose except general identification. It follows that if it becomes necessary to establish the exact boundary, the deeds will almost invariably have to be supplemented by such inferences as may be drawn from topographical features which existed, or may be supposed to have existed, when the conveyances were executed.”

30. Of course, as Mr Oughton emphasised, the fact that a plan is included for the purposes of identification only does not mean that it is irrelevant. It will not prevail over a clear verbal description, but in the absence of such a description the plan should be taken into account together with other admissible evidence and may be decisive. The clearer the plan, the more helpful it may be, but it must be interpreted as part of the conveyance as a whole and with regard to any relevant and admissible background material.

Issue 1: Was the disputed parcel included in the 1991 Conveyance?

31. The necessary premise of the FTT’s decision is that, having conveyed their Barn in 1986, and having decided to convey their House in 1991, Mr and Mrs Field nevertheless wished to retain for themselves a small strip of land in the middle of the open yard between the two. It must also be inferred that Mr Scott, the purchaser, agreed that the transaction should have that effect. Such a desire seems both improbable and technically difficult to achieve, given that the area of land in question was unmarked by physical boundaries.

32. In Parmar v Upton [2015] EWCA Civ 795, at [14] Briggs LJ] described as “plain and simple common sense” the proposition that:

“Landowners do not, in general, reserve narrow and inaccessible strips of land along the edge of property conveyed which abuts an established boundary with land in separate ownership, unless for some very good reason, such as the preservation of a ransom strip, designed to enable the seller to share in any subsequent development value which necessitates an access road or other services being constructed across the strip.”

33. For such an improbable intention credibly to be attributed to the parties one would first expect it to be reflected clearly in the 1991 Conveyance itself or at least in some other piece of admissible material.

34. The 1991 Conveyance consists of only six clauses. It identifies the Property being conveyed as “the land and detached house known as Chapel House”. The plan on which the Property is delineated is stated to be “for the purposes of identification only”. Without more those verbal and graphical descriptions are clear and indicate that the whole of the land and detached house known as Chapel House was being sold. Nothing in the description of the subject, or in the plan itself, suggests an intention to retain any part of the property then occupied by the vendor. In particular, there is no statement that the sale is of part only nor any careful demarcation of the boundary across the yard, as would undoubtedly have been necessary to ensure that both parties were clear what they were buying and selling if it was to be less than the whole.

35. Omissions from the Conveyance also clearly indicate that this was not intended by either party to be a conveyance of part only of the vendors’ property. It reserves no easements for the benefit of any retained land to enable the vendors to reach it. Nor does it grant any easements for the purchasers to traverse the orphaned parcel or maintain or lay any service pipes beneath it. Unlike the 1986 Conveyance the 1991 Conveyance includes no acknowledgement of the right of the purchaser to production of the 1976 Conveyance by which the vendors had acquired the property. That omission demonstrates that the vendors did not intend to retain the title deeds, as they would have done had they been selling only part of their property.

36. In short, without going outside the four corners of the document, it is possible to be quite sure that the subject of the 1991 Conveyance was the whole of the property belonging to the vendors.

37. The FTT gave two reasons for concluding that the disputed parcel of land was excluded from the 1991 Conveyance.

38. First, it considered that the description of the property conveyed was ambiguous so that the plan and any other appropriate evidence could be used to construe the parties’ intentions. That much may have been agreed before the FTT but for the reasons I have already given when the Conveyance is read as a whole it is not at all ambiguous.

39. Secondly, the FTT considered it could properly have regard to the contents of the purchase report “to the extent that it very likely reflects replies to preliminary enquiries provided by Mr and Mrs Field’s solicitors” and cited a decision of the Court of Appeal, Toplis v Green in that connection. This enabled the FTT to refer to the Smiths Gore plan with its diagonal line running from points B to C clearly following a different course from the boundary in the 1986 Conveyance and which “would have differed considerably on that plan [i.e. the 1991 Conveyance plan] had it been intended that the disputed land be included”.

40. There a number of difficulties with this approach. The conveyancing file was not in evidence. There is nothing in Toplis v Green about inferring the content of replies to preliminary enquiries from a report on title. The author of the report was clearly mistaken in describing the relevant boundary as marked between B and C by walls or fences, and that would have been apparent to the purchasers on inspection. It seems equally likely that the purchaser’s solicitor was making assumptions based on the obligations in the 1986 Conveyance rather than passing on information gleaned from preliminary enquiries. In any event, the purchaser had been warned by his own solicitor that the plan was for identification purposes only and that he should check the boundaries for himself (which in all probability is also what the replies would have said). Speculation about the content of replies to preliminary enquiries, or any other aspect of the conveyancing process, is just that. I therefore do not think that anything can usefully be inferred about the parties’ intentions from the report on purchase or the Smiths Gore plan, and certainly nothing which justifies treating the general shape of the boundary on the plan as definitive of its location or as trumping the clear effect of the 1991 Conveyance read as a whole.

41. For the respondents, Mr Oughton acknowledged that, as a general proposition, it is unlikely that a vendor would wish to retain a small portion of land without express mention in the conveyance. The weight of that presumption ought to vary with the circumstances, and Mr Oughton argued that in this case it was outweighed by the clear intention of both parties to the 1991 Conveyance was not to convey the disputed land. I can find no such intention in the document which, to my reading, is decisively to the opposite effect. Nor does the fact that the disputed parcel is relatively substantial and in quite a prominent location in the middle of the yard suggest that Mr and Mrs Field were any more likely to wish to retain it, and no good reason was suggested why they might have wanted to.

42. Mr Oughton invited the Tribunal to accord “a measure of weighted deference” to the findings and conclusions of the FTT as Mummery LJ had said in Wilkinson v Farmer [2010] EWCA Civ 1148 at [25] it was appropriate for appellate courts to do when considering appeals from Adjudicators to H.M. Land Registry and their Deputies. The route of appeal from decisions of the FTT, the jurisdictional successor to the Adjudicators, now lies within the specialist tribunals structure. This Tribunal approaches appeals from decisions of the FTT in any of its jurisdictions in the same way; it will rarely interfere with findings of fact made after consideration of all the relevant evidence but it will not be deterred by deference from correcting errors of law.

43. I also reject Mr Oughton’s submission that the appellant should not be allowed to rely on the limitations of the 1991 Conveyance plan while seeking to uphold the FTT’s conclusions on the 1986 Conveyance which featured an equally inept plan. Each document must be read as a whole and interpreted according to its own terms.

44. In my judgment the FTT reached the wrong conclusion about the 1991 Conveyance. That document was effective to convey all of the property at Chapel House remaining in the ownership of the vendors at the time of its completion.

45. The question then arises whether the disputed parcel of land was still held with the House in 1991 or whether it had been included with the Barn in the 1986 Conveyance. That question is the subject of the respondents’ cross appeal.

Issue 2: Was the disputed parcel included in the 1986 Conveyance?

46. The cross appeal on the effect of the 1986 Conveyance was founded on the submission by Mr Oughton that the points marked B, C and D on the Conveyance plan did not represent the features which the FTT had found them to represent. In particular he suggested that point B should be construed as the end of the low wall running north-south, since demolished, and now the site of a gate post, rather than some distance to the north of that location. That was on the basis that the end of the wall was more readily identified, and therefore the more likely reference point. Points C and D, which the FTT found were the opposite ends of the gable wall, were also problematic because of the express obligation to erect a fence or wall along that boundary.

47. I reject Mr Oughton’s submission about the location of point B. Both the red edging and the hatching showing the land over which a right of way was granted indicate that point B was not at the southern end of the low party wall, but was some distance to the north, beyond the point at which a pipe is shown crossing the boundary on the 1986 Conveyance plan. It is not known which building, if any, was served by the pipe but it provides a clear reference point and the boundary changes direction at B, to the north of the pipe.

48. There is much greater doubt in my mind about the location of points C and D, but not enough to invalidate the FTT’s basic conclusion that the 1986 Conveyance did not include the whole of the disputed land. The general route of the boundary between points B, C and D is apparent from the 1986 Conveyance plan and the FTT was plainly correct when it concluded that the boundary was not in the same location as the boundary shown on the 1991 Conveyance plan. For the reasons I have given in dealing with issue 1, there was no orphaned parcel of land between the two boundaries and the 2015 Transfer was without content. There is therefore no need to consider the appellant’s appeal against the FTT’s conclusion on the adequacy of the 2015 Transfer.

49. Those conclusions need not require that points B and C on the 1986 Conveyance plan must be in exactly the position assumed by the FTT. The FTT interpreted the 1986 Conveyance plan as showing that the boundary was formed between points C and D by the gable wall of the Barn. But because of the thickness of the line that is not the only possible interpretation of the plan. On the registered title plan the boundary is indeed shown as following the gable wall, but, as the parties agree, that simply reflects Land Registry practice of using physical features shown on the ordnance survey to indicate general boundaries without purporting to define their precise location. The parties also agree that for the boundary to be along the wall itself makes a nonsense of the covenant at clause 3(b) of the 1986 Conveyance which required the Purchasers to erect and maintain a fence or wall along exactly that boundary. Bearing in mind that the plan to the 1986 Conveyance is stated to be for the purpose of identification only, the obvious and to my mind inescapable conclusion is that the boundary between C and D was intended to be at some distance from the gable wall and to be separated from the remainder of the yard by the new wall or fence.

50. In the event no new wall or fence was ever constructed but the case for interpreting the 1986 Conveyance as including with the Barn a strip of land running alongside the gable wall is strengthened by the route of the boundary beyond point D. After D the boundary turns through 90 degrees and runs southwest, parallel to the flank wall of the Barn. On the ground the boundary does not follow the flank wall but is formed by a retaining wall running parallel to it. The retaining wall has been reconstructed since 1986 but my understanding was that the presence of a wall along that boundary is not a recent change. The retaining wall is required because the ground level in the field to the south of the Barn is higher than the level of the yard and the ground floor of the Barn. The gap between the retaining wall and the flank wall of the Barn is a matter of a few feet at most, but no doubt it allows useful access to the wall from land within the same ownership. A similar facility may have been in the minds of the parties between points C and D. Reading the Conveyance as a whole, that would make sense of the otherwise senseless obligation to fence between those points.

51. The parties to the 1986 Conveyance also agreed that there should be “a gate” between point C and point B. If, as has been assumed, point C is the northern corner of the gable end, the distance between point C and B is much wider than could be spanned by a single gate. No gate was erected in 1986 but since the parties fell into dispute in 2011 gates had been erected, and it has taken three to span the gap, a pedestrian gate and a pair of wide farmyard gates. It would be wrong to read too much into this, other than lending some further support to point C being at a little distance from the corner of the gable wall.

Disposal

52. No application has been made for a determined boundary between the House and the Barn; it was therefore not open to the FTT to define the precise location of the boundary between points B, C and D on the 1986 Conveyance plan. Nor was it asked to give a direction to the registrar that would delineate the general boundary more precisely than the registered title plans do at present, and it did not do so.

53. It was asked only to consider the appellant’s objection to registration of the land purportedly include in the 2015 Transfer. I uphold that objection and allow the appeal. I direct the Chief Land Registrar to reject the respondents’ application for registration.

54. If the exact location of the boundary remains important to the parties it ought to be possible for them now to reach a sensible agreement.

Martin Rodger QC

Deputy Chamber President

19 February 2021