[New search]

[Printable PDF version]

[Help]

| |

|

Neutral Citation Number: [2017] EWCA Civ 359 |

| |

|

Case No: A1/2016/2172 |

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION)

ON APPEAL FROM Queen's Bench Division, Technology and Construction Court

Mr Roger ter Haar QC

HT-2016-000037

| |

|

Royal Courts of Justice

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

| |

|

18/05/2017 |

B e f o r e :

LORD JUSTICE JACKSON

and

LORD JUSTICE BEATSON

____________________

Between:

| |

Sutton Housing Partnership Limited

|

Appellant

|

| |

- and -

|

|

| |

Rydon Maintenance Limited

|

Respondent

|

____________________

Steven Walker QC (instructed by SA Law LLP) for the Appellant

Jessica Stephens (instructed by Rydon Group, Legal Operations) for the Respondent

Hearing date : Thursday 27th April 2017

____________________

HTML VERSION OF JUDGMENT APPROVED�

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

Lord Justice Jackson :

- This judgment is in four parts, namely:

Part 1 Introduction

- This is an appeal by the employer under a construction contract against the dismissal of their claim for a declaration. The principal issue is whether the figures set out for minimum acceptable performance in three tables headed "example" are contractually binding or merely illustrative.

- Sutton Housing Partnership ("Sutton") manage the housing stock of the London Borough of Sutton. Sutton is claimant in the litigation and appellant in this court. Rydon Maintenance Limited ("Rydon") is a contractor which specialises in the maintenance and repair of housing. Rydon is defendant in the litigation and respondent in this court.

- After these introductory remarks, I must now turn to the facts.

Part 2 The facts

- By a contract dated 14th May 2013, Sutton engaged Rydon to carry out maintenance and repairs to the housing stock which the London Borough of Sutton own. The contract was based on the National Housing Federation's standard form contract 2011.

- Clause 1 of the contract conditions ("the conditions") in conjunction with the contract details provided that the contract should run from 1st July 2013 to 30th June 2018, subject to earlier termination under clause 13 of the conditions.

- Clause 1 of the contract conditions contained the following definitions:

""Key Performance Indicator" or "KPI" - a Key Performance Indicator by which the Service Provider's performance of the Works is measured as set out in the KPI Framework;

"KPI Framework" the Contract Document setting out how KPIs are to be measured;

"KPI Performance Target" the performance target for a KPI as set out in the KPI Framework;

"Minimum Acceptable Performance" the minimum level of performance as measured by a KPI (as set out in the KPI Framework) that the Client is prepared to tolerate such that if performance is worse than that level for that KPI the Client can serve a notice under Clause 12.1.9

"

I shall use the abbreviation "MAPs" for the minimum acceptable levels of performance referred to in clause 1.

- Clause 9 of the conditions set out the provisions governing payment. Clause 9.3.4 provided:

"Where part of the Service Provider's payment for Central Overheads and Profit or Profit only is variable, payment of the variable element will depend on the Service Provider's achieving the KPI target set out in the KPI Framework. The KPI Framework sets out how the amount payable for the variable element is determined."

- Clause 12 of the conditions set out provisions governing monitoring. Clause 12.1.9 provided:

"Where the Service Provider's performance of the Works is worse than the Minimum Acceptable Performance level for any one or more KPIs the Client may serve a written notice on the Service Provider to that effect. The notice will:

- give details of each KPI where performance is worse than the Minimum Acceptable Performance level, stating:

- the performance level achieved;

- the period over which that KPI performance was measured; and

- that performance in relation to that KPI is worse than the Minimum Acceptable Performance level;

- tell the Service Provider within what period (of no less than 1 (one) Month from the date of the notice), performance in relation to each of those KPIs must be improved so that it is better than Minimum Acceptable Performance and over what period (not exceeding 3 (three) Months starting on the date 1 (one) Month from the date of notice) performance that is better than Minimum Acceptable Performance for those KPIs must be maintained; and

- warn the Service Provider that if performance is not improved so that it is better than Minimum Acceptable Performance for all of those KPIs within the period specified or that performance better than the Minimum Acceptable Performance is not maintained over the period specified, this Contract may be terminated for Service Provider Default."

- Clause 13.1.1 of the conditions provided:

"13.1.1 The Client may terminate this Contract for Service Provider Default by written notice to the Service Provider having immediate effect, if the Service Provider:

- fails to improve performance of the Works above Minimum Acceptable Performance for any KPI following the process set out in Clause 12.1"

- Clause 13.5 of the conditions permitted either party to terminate the contract upon six months notice after the expiry of the first two years.

- The KPI Framework ("the framework") was a contractual document and it is central to the issues in this appeal.

- Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the framework provided as follows:

"1. Purpose of the KPIs

In this Contract key performance indicators ("KPIs") are used for the following purposes:

- to monitor performance of the Contract, with a view to both the Client and Service Provider having data which they will review at progress and other meetings so that each of them can bring forward suggestions for the improvement of the performance of the Contract and the delivery of the Works;

- to incentivise performance in specific areas through linking part of the payment of Profit to KPI performance;

- to identify performance below the performance target which, if continued for 3 monthly Measurement Periods, or applying to 3 or more KPIs, leads to a requirement for the Service Provider to produce a Remedial Plan; and

- to identify performance that is below the minimum standard that the Client is prepared to accept ("Minimum Acceptable Performance") and which, if not improved, will lead ultimately to termination of the Contract for Service Provider Default.

2. Incentivisation

The Service Provider's Profit depends on the Service Provider achieving performance targets for certain KPIs.

Each adjustment of the percentage payable for Profit will be based on the Works undertaken in the previous quarter.

The part of the payment for Profit that depends on achieving KPI targets is payable Quarterly in arrears based on performance over that Quarter. This will be the subject of a separate Valuation when the KPI data is available.

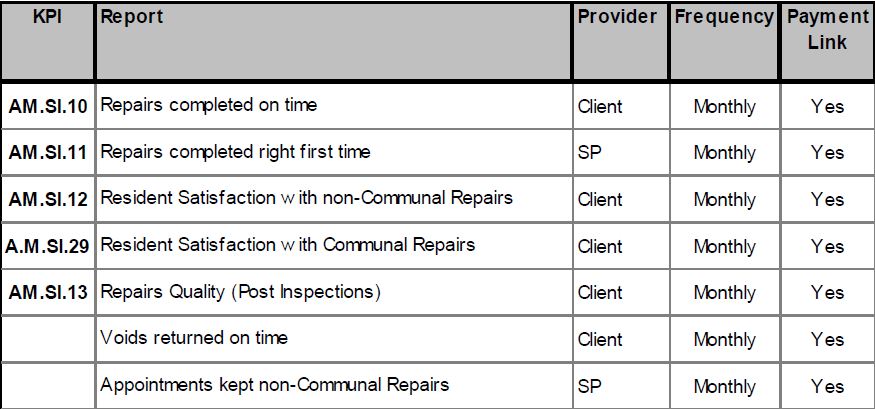

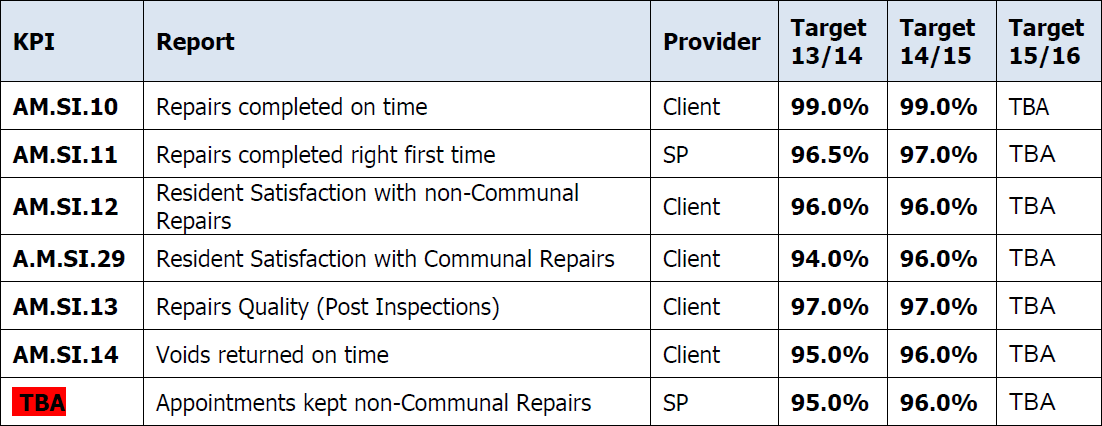

Incentivisation applies to Profit only. The KPIs where performance counts towards payment of the percentage for Profit set out in the following table.

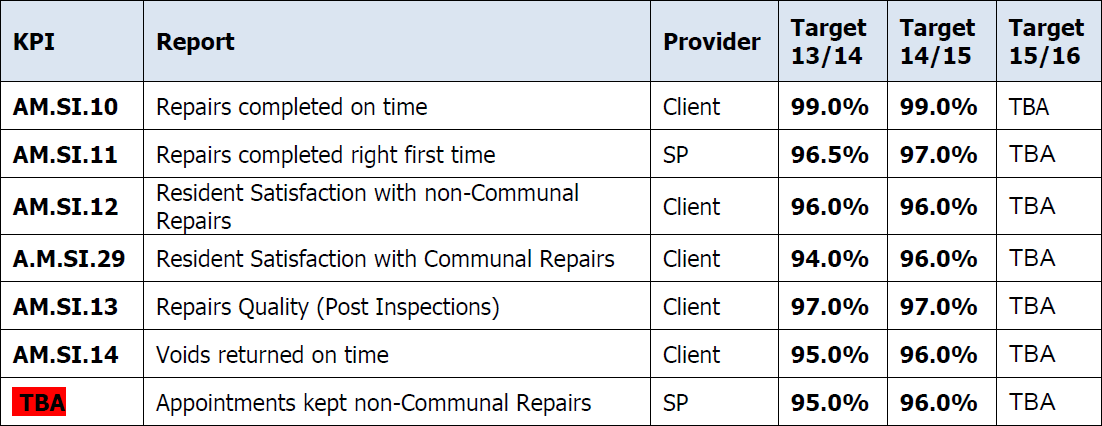

KPI targets are set out for each KPI in this document. The amount payable for profit is based on the following criteria for each KPI.

| Criteria |

Profit proportion payable |

| Failing to meet the minimum requirement (Profit Performance Threshold) |

Zero |

| Meeting the minimum requirement but not meeting Target |

% Pro-rata between the Profit Performance Threshold and the Target |

| Exceeding target |

% Pro-rata between the Profit Performance Threshold and the Target (to a maximum of 20% for the aggregate of all KPIs) |

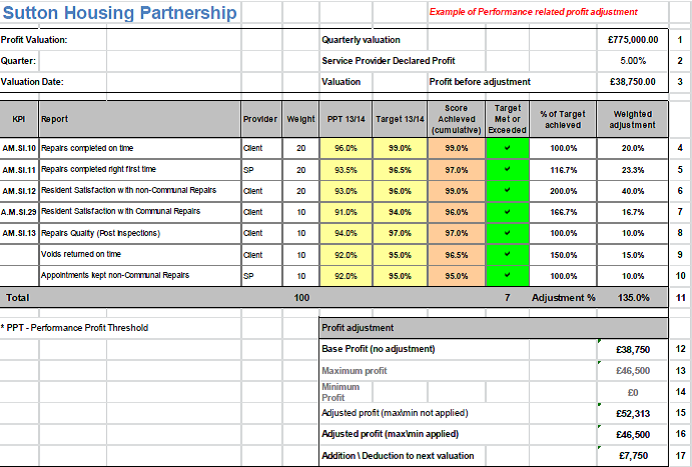

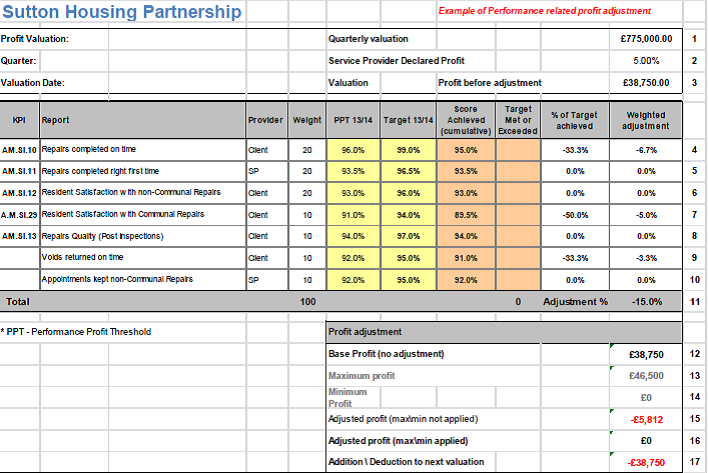

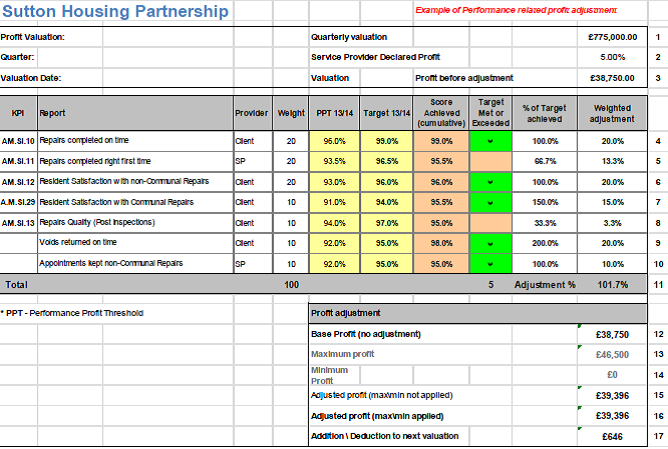

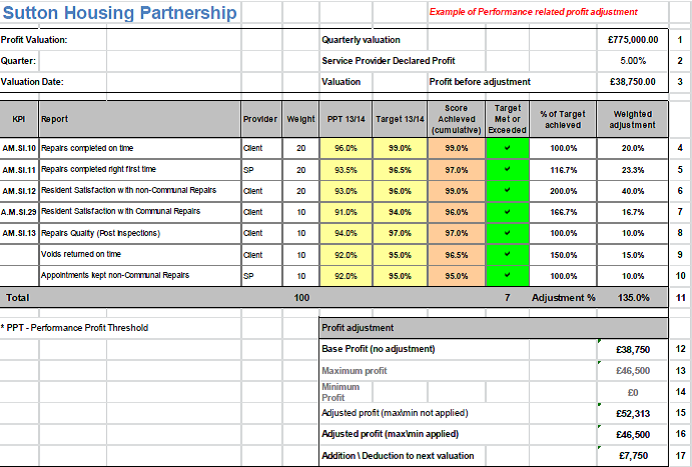

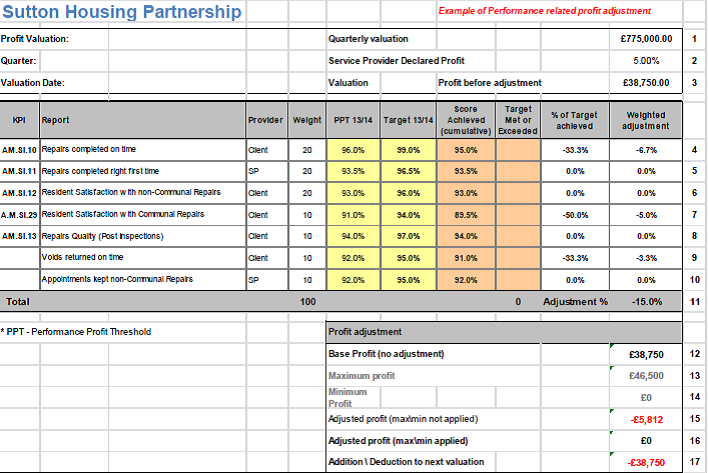

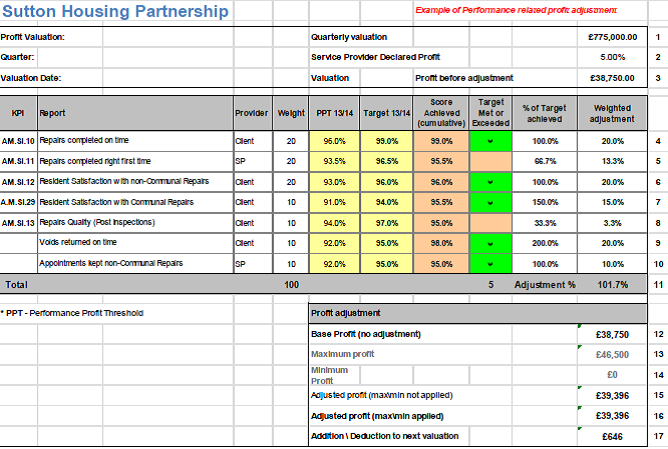

The relative importance of different KPIs is been reflected by a weighting value as set out in the weighting column of the example given below. The profit paid will be calculated on a range from 0% of profit paid if the performance profit threshold (PPT) is not achieved to 100% if the target is reached and more if exceeded.

The amount of profit will be calculated based on the quarterly average of the profit linked performance indicators and any resulting additions or deductions made at the following quarter's valuation.

The amount of profit due in each work type will be calculated by inputting the performance figures into the KPI matrix as set out in the example below. This calculates exactly where the performance is on the range of scores between the minimum acceptable standard, the target and beyond.

Where performance exceeds targets within a work type the Client will pay up to an additional 20% (maximum) on the Service Providers profit margin. The scores for individual KPIs are aggregated for the purposes of calculating the profit payable.

The examples below give results for different scenarios."

- There then follow three examples. I attach the examples as an appendix to this judgment.

- Paragraphs 3 to 5 of the framework provided:

"3. Remedial Plan

The Contract Conditions require the production of a Remedial Plan if the Service Provider fails to achieve the Performance Target(s) for:

- 3 or more KPIs in relation to any Measurement Period; or

- the same KPI for 3 or more monthly Measurement Periods or one quarterly Measurement Period.

The Remedial Plan is subject to the approval of the Client and if the Service Provider provides 3 drafts of the Remedial Plan without one being acceptable to the Client, this will be Service Provider Default.

The Service Provider must implement the Remedial Plan and a failure to do so will be a breach of this Contract.

4. Minimum Acceptable Performance

KPIs have Minimum Acceptable Performance (=PPT) levels. Performance below PPT for any KPI may result in the Contract being terminated for Service Provider Default under Clause 12.4.2 of the Contract Conditions.

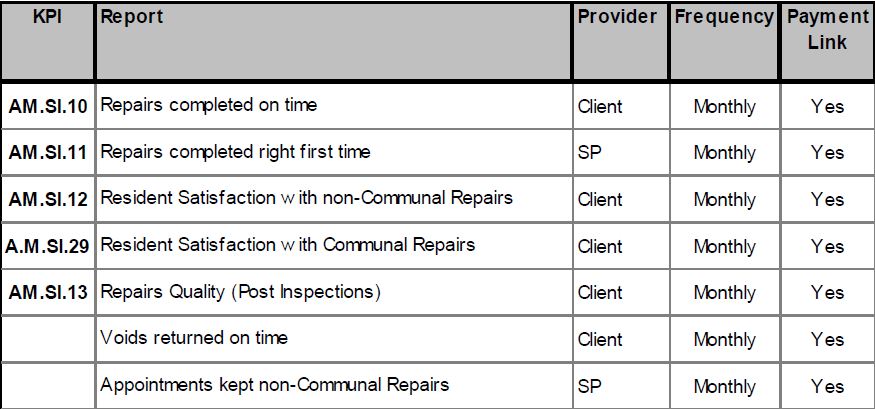

5. KPI Targets

Targets have been set for KPIs as shown in the table below. Targets for years 2015 onwards will be set by the Client in consultation with the Service Provider. The Client's decision on targets is final.

- Although the framework is poorly drafted, it is important to note that MAPs and Performance Profit Thresholds ("PPTs") are different ways of describing the same thing. For simplicity, I shall always refer to them as MAPs.

- I shall use the term "bonuses" to describe the variable payments made under the incentivisation scheme set out in paragraph 2 of the framework.

- Having set up the contractual arrangements, the parties duly proceeded to implement them. Unfortunately difficulties arose during 2014. Sutton became dissatisfied with Rydon's service.

- Between October and November 2014 acrimonious correspondence passed between the parties. It is not necessary to set out that correspondence. I should, however, mention that at no point did Rydon suggest that the contract failed to specify MAPs.

- During the course of that correspondence, on 12th November 2014, Sutton served a notice on Rydon pursuant to clause 12.1.9 of the conditions. In that notice Sutton asserted that Rydon had failed to achieve the contractual MAPs in the following respects:

|

KPI |

Description |

KPI Performance Targets 2014/2015 |

Minimum Acceptable Performance (M.A.P.) |

Performance Achieved Jul-Sep 2014 (Oct 2014) |

Performance Achieved Compared to M.A.P. |

AM.SI.11

|

Repairs completed right first time |

97.0% |

94.0% |

74.5%

(76.0%) |

-19.5%

(-18.0%) |

AM.SI.12

|

Resident satisfaction with noncommunal repairs |

96.0% |

93.0% |

82.5%

(82.3%) |

-10.5%

(-10.7%) |

AM.SI.29

|

Resident satisfaction with communal repairs |

96.0% |

93.0% |

61.5%

(85.2%) |

-35.5%

(-7.8%) |

AM.SI.13

|

Repairs quality (Post inspection) |

97.0% |

94.0% |

84.1%

(61.5%) |

-9.9%

(-32.5%) |

AM.SI.14

|

Voids returned on time |

96.0% |

93.0% |

0.0%

(n/a) |

-93.0%

(n/a) |

| |

Appointments kept for noncommunal repairs |

96.0% |

93.0% |

Rydon to provide data |

Rydon to provide data |

- In that notice Sutton gave Rydon one month in which to achieve levels of performance above the MAPs. Sutton stated that if Rydon did not improve their performance within one month, Sutton would terminate the contract under clause 13.1 of the conditions for Service Provider Default.

- During the following month Sutton continued to be dissatisfied with Rydon's level of service. On 19th December 2014 Sutton served a notice terminating the contract for Service Provider Default pursuant to clause 13.1 of the conditions.

- Subsequently there was a dispute between the parties about the lawfulness of Sutton's determination, or purported determination, of the contract. One of the contentions raised by Rydon was that the contract did not specify any MAPs. Therefore Sutton could not terminate the contract pursuant to clauses 12.1.9 and 13.1 of the conditions.

- There was an adjudication between the parties in which Rydon was successful. In order to challenge the adjudicator's decision, Sutton commenced the present proceedings.

Part 3 The present proceedings

- By a claim form issued in the Technology and Construction Court under Part 8 of the Civil Procedure Rules on 12th February 2016, Sutton claimed declaratory relief against Rydon. One of the declarations that Sutton claimed (and the only declaration relevant for present purposes) was:

"The Contract contains the MAP levels referred to in Sutton's notices dated 12th November 2014 and 19th December 2014."

- In its particulars of claim Sutton contended that, either expressly or by implication, the contract specified the following MAPs:

| KPI |

Report |

13/14 |

14/15 |

| AM.SI.11 |

Repairs completed right first time |

93.5% |

94.0% |

| AM.SI.12 |

Resident Satisfaction with non Communal repairs |

93.0% |

93.0% |

| AM.SI.29 |

Resident Satisfaction with Communal repairs |

91.0% |

93.0% |

| AM.SI.13 |

Repairs Quality (Post Inspection) |

94.0% |

94.0% |

| AM.SI.14 |

Voids returned on time |

92.0% |

93.0% |

| |

Appointments kept non-Communal Repairs |

92.0% |

93.0% |

- The basis for that plea is as follows. The figures for 2013/2014 are shown in column 4 of examples 1, 2 and 3 set out in paragraph 2 of the KPI framework which I have attached as an appendix to this judgment. It can be seen that each of those figures is 3% less than the specified target figure. The figures pleaded for the year 2014/2015 are derived arithmetically, namely by deducting 3% from each of the target figures set out in paragraph 5 of the framework.

- Rydon served a defence seeking to uphold the adjudicator's decision. In particular, Rydon denied that the contract specified any MAPs, either expressly or by implication.

- The action came on for trial before Mr Roger ter Haar QC sitting as a deputy judge of the High Court in the Technology and Construction Court ("the judge") on 22nd April 2016. The parties asked the judge to determine two issues. Issue 1 was:

"Whether the Contract contained MAP levels set out in Sutton's notices dated 12th November 2014 and 19th December 2014."

- The judge handed down his reserved judgment on 12th May 2016. He found in favour of Rydon on issue 1 and granted the following declaration:

"On the proper construction of the Contract between the parties dated 14 May 2013, the Contract does not provide for the Minimum Acceptable Performance levels."

- The judge gave four reasons for his decision in paragraphs 54 to 58 of his judgment as follows:

"54. Firstly, in my view whilst it may not be strictly necessary to construe the Contract contra proferentem, the Court should proceed with some care before concluding that one party is entitled to terminate a relatively long-term contract unless the Contract is clear as to the circumstances in which the party seeking to terminate is entitled to do so.

55. Secondly, if the Contract intended the "examples" in paragraph 2 of the KPI Framework to be binding for the purposes of defining either entitlement to profit or entitlement to terminate, I would expect the Contract to say so.

56. Thirdly, I note that in paragraph 5 of the KPI Framework, "the Client's decision on targets is final". I read this as applying to the years from 2015 onwards, but if Sutton's argument is right it would mean that Sutton could unilaterally decide Target levels for the years 2015/2016 onwards which would indirectly define MAP/PPT levels (which, on Sutton's argument, would be in each case exactly 3% less than the level determined unilaterally by Sutton) and thereby Sutton would be able to determine unilaterally the hurdle which Rydon would have to clear to avoid Sutton having an unchallengeable right to terminate the Contract.

57. Fourthly, whilst I accept Sutton's submission that this means that Clause 12.1.9 loses much if not all of its efficacy, I also accept Rydon's submission that this does not render the Contract unworkable: the Remedial Plan provisions give Sutton powerful rights (including termination) in the event of unsatisfactory performance by Rydon.

58. For these reasons, which largely amount to an acceptance of Ms. Stephens's submissions to this Court, I hold that the Contract does not expressly determine the MAP/PPT levels for each KPI or provide a machinery for doing so."

- Having reached that conclusion the judge rejected, much more briefly, the argument that the suggested terms could be implied.

- The judge very fairly acknowledged that the issues were finely balanced. He granted permission to appeal, stating "the contrary position is well arguable".

- Sutton were aggrieved by the judge's decision. Accordingly they appealed to the Court of Appeal.

Part 4 The appeal to the Court of Appeal

- By an appellant's notice filed on 27th May 2016 Sutton appealed to the Court of Appeal on two grounds. First, the contract expressly provided for the MAPs pleaded in the particulars of claim. Secondly, in so far as the contract did not do that expressly, it did so by implication.

- The appeal came on for hearing on 27th April 2017. Mr Steven Walker QC appeared for Sutton, as he had in the court below. Ms Jessica Stephens appeared for Rydon, as she had in the court below. I am grateful to both counsel for their assistance.

- There has been much debate about the four reasons stated by the judge in support of his conclusion. I shall therefore begin by commenting on each of the judge's reasons.

- As to the judge's first reason, he was right to say that this is not a case in which the contra proferentem rule is of assistance. The judge was also correct to say that the court should proceed with care when determining whether contractual provisions are sufficiently clear to permit the termination of a relatively long-term contract. I therefore reject Mr Walker's criticisms of paragraph 54 of the judgment.

- The judge's second reason is not a powerful one. The KPI framework is a poorly drafted document. It is common ground that the parties must have intended to provide MAPs. If there were no MAPs, Sutton would lose a valuable mechanism for termination and Rydon would lose their entitlement to bonuses. It is not possible to calculate what bonuses (if any) are due to Rydon under paragraph 2 of the KPI framework without having a set of MAPS.

- Ms Stephens accepts that the parties must have intended to specify MAPs and says that their omission to do so was inadvertent. Mr Walker says that the parties intended to specify MAPs and succeeded in doing so, albeit by a somewhat circuitous route.

- In Re Sigma Finance Corp (in admin. rec) [2008] EWCA Civ 1303; [2009] BCC 393 Lord Neuberger MR stated as follows at [101]:

"Further, I do not think it is normally convincing to argue that, if the parties had meant a phrase to have a particular effect, they would have made the point in different or clearer terms."

Although the Supreme Court partially reversed the Court of Appeal's decision in Sigma, they did not cast doubt on Lord Neuberger's approach to construction in paragraph 101. That passage is in my view apposite to the judge's second reason.

- The judge's third reason does have a degree of force, but no more. It is true that from the third year onwards Sutton were free to set the targets. On the other hand, from year three onwards Rydon was entitled to terminate the contract under clause 13.5. So Rydon was not locked into a disadvantageous contract. There was express agreement that Sutton could unilaterally determine the target figures from year three onwards. If Rydon did not like the target figures then it could withdraw.

- As to reason four, the judge accepts that without any MAPs clause 12.1.9 is inoperable. That means that the corresponding termination provision in clause 13.1.1 is ineffective. These are powerful pointers in support of Sutton's case. The parties can hardly have intended to neutralise the principal contractual provision enabling the employer to terminate for poor service.

- The judge is right to say that even without clause 12.1.9 Sutton still had other means of termination. On the other hand, the procedure set out in the Remedial Plan provisions is cumbersome and long drawn out. Sutton would obviously wish to keep the simpler and swifter procedure under clause 12.1.9 in conjunction with clause 13.1.1.

- Let me now stand back from the judge's reasons and tackle the question of construction head on.

- Lawyers are now lucky enough to live in a world overflowing with appellate guidance on how to construe contracts. I will not add to that superfluity, but will instead select the authorities and passages of greatest relevance to the present problem.

- Rainy Sky SA v Kookmin Bank [2011] UKSC 50; [2011] 1 WLR 2900 was an appeal concerning the construction of shipbuilders' refund guarantees given pursuant to six shipbuilding contracts. At [14] Lord Clarke summarised the recent case law on construing commercial contracts as follows:

"For the most part, the correct approach to construction of the Bonds, as in the case of any contract, was not in dispute. The principles have been discussed in many cases, notably of course, as Lord Neuberger MR said in Pink Floyd Music Ltd v EMI Records Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 1429; [2011] 1 WLR 770 at para 17, by Lord Hoffmann in Mannai Investment Co Ltd v Eagle Star Life Assurance Co Ltd [1997] AC 749, passim, in Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society [1998] 1 WLR 896, 912F-913G and in Chartbrook Ltd v Persimmon Homes Ltd [2009] 1 AC 1101, paras 21-26. I agree with Lord Neuberger (also at para 17) that those cases show that the ultimate aim of interpreting a provision in a contract, especially a commercial contract, is to determine what the parties meant by the language used, which involves ascertaining what a reasonable person would have understood the parties to have meant. As Lord Hoffmann made clear in the first of the principles he summarised in the Investors Compensation Scheme case at page 912H, the relevant reasonable person is one who has all the background knowledge which would reasonably have been available to the parties in the situation in which they were at the time of the contract."

- In Arnold v Britton and others [2015] UKSC 36; [2015] AC 1619 the Supreme Court was construing the service charge provisions in leases. The court upheld the natural meaning of those provisions, even though they operated harshly against the tenants.

- At [15] [20] Lord Neuberger gave the following guidance on the interpretation of contractual provisions:

"15 When interpreting a written contract, the court is concerned to identify the intention of the parties by reference to "what a reasonable person having all the background knowledge which would have been available to the parties would have understood them to be using the language in the contract to mean", to quote Lord Hoffmann in Chartbrook Ltd v Persimmon Homes Ltd [2009] AC 1101, para 14. And it does so by focussing on the meaning of the relevant words, in this case clause 3(2) of each of the 25 leases, in their documentary, factual and commercial context. That meaning has to be assessed in the light of (i) the natural and ordinary meaning of the clause, (ii) any other relevant provisions of the lease, (iii) the overall purpose of the clause and the lease, (iv) the facts and circumstances known or assumed by the parties at the time that the document was executed, and (v) commercial common sense, but (vi) disregarding subjective evidence of any party's intentions. In this connection, see Prenn [1971] 1 WLR 1381, 13841386; Reardon Smith Line Ltd v Yngvar Hansen-Tangen (trading as HE Hansen-Tangen) [1976] 1 WLR 989, 995997, per Lord Wilberforce; Bank of Credit and Commerce International SA v Ali [2002] 1 AC 251, para 8, per Lord Bingham of Cornhill; and the survey of more recent authorities in Rainy Sky [2011] 1 WLR 2900, paras 2130, per Lord Clarke of Stone-cum-Ebony JSC.

16 For present purposes, I think it is important to emphasise seven factors.

17 First, the reliance placed in some cases on commercial common sense and surrounding circumstances (eg in Chartbrook [2009] AC 1101, paras 1626) should not be invoked to undervalue the importance of the language of the provision which is to be construed. The exercise of interpreting a provision involves identifying what the parties meant through the eyes of a reasonable reader, and, save perhaps in a very unusual case, that meaning is most obviously to be gleaned from the language of the provision. Unlike commercial common sense and the surrounding circumstances, the parties have control over the language they use in a contract. And, again save perhaps in a very unusual case, the parties must have been specifically focussing on the issue covered by the provision when agreeing the wording of that provision.

18 Secondly, when it comes to considering the centrally relevant words to be interpreted, I accept that the less clear they are, or, to put it another way, the worse their drafting, the more ready the court can properly be to depart from their natural meaning. That is simply the obverse of the sensible proposition that the clearer the natural meaning the more difficult it is to justify departing from it. However, that does not justify the court embarking on an exercise of searching for, let alone constructing, drafting infelicities in order to facilitate a departure from the natural meaning. If there is a specific error in the drafting, it may often have no relevance to the issue of interpretation which the court has to resolve.

19 The third point I should mention is that commercial common sense is not to be invoked retrospectively. The mere fact that a contractual arrangement, if interpreted according to its natural language, has worked out badly, or even disastrously, for one of the parties is not a reason for departing from the natural language. Commercial common sense is only relevant to the extent of how matters would or could have been perceived by the parties, or by reasonable people in the position of the parties, as at the date that the contract was made. Judicial observations such as those of Lord Reid in Wickman Machine Tools Sales Ltd v L Schuler AG [1974] AC 235, 251 and Lord Diplock in Antaios Cia Naviera SA v Salen Rederierna AB (The Antaios) [1985] AC 191, 201, quoted by Lord Carnwath JSC at para 110, have to be read and applied bearing that important point in mind.

20 Fourthly, while commercial common sense is a very important factor to take into account when interpreting a contract, a court should be very slow to reject the natural meaning of a provision as correct simply because it appears to be a very imprudent term for one of the parties to have agreed, even ignoring the benefit of wisdom of hindsight. The purpose of interpretation is to identify what the parties have agreed, not what the court thinks that they should have agreed. Experience shows that it is by no means unknown for people to enter into arrangements which are ill-advised, even ignoring the benefit of wisdom of hindsight, and it is not the function of a court when interpreting an agreement to relieve a party from the consequences of his imprudence or poor advice. Accordingly, when interpreting a contract a judge should avoid re-writing it in an attempt to assist an unwise party or to penalise an astute party."

- Bearing in mind that guidance, I now turn to the present issue.

- If Rydon's contentions are correct, the contract contains no MAPs. Therefore the bonus provisions for Rydon's benefit in the incentivisation scheme are inoperable. Likewise the termination provisions in clause 12.9.1 together with clause 13.1.1, for the benefit of Sutton, are inoperable.

- The contract in this case is a commercial one, made between a local authority and a building contractor. Self-evidently, Rydon intended to receive all the bonuses which were due to it under the incentivisation scheme. That was only possible if the contract specified MAPs. Also self-evidently, Sutton intended to retain their valuable power to terminate for poor service under clause 12.1.9 in conjunction with clause 13.1.1. That was only feasible if the contract contained MAPs.

- Therefore both parties must have intended (and any reasonable or indeed unreasonable person standing in the shoes of either party would have intended) the contract to specify MAPs. The only place where MAPs appear is in the three so-called "examples" in the framework. In my view, applying the approach mandated by the Supreme Court in Rainy Sky and Arnold, the contract properly construed must mean that the MAP figures set out in examples 1, 2 and 3 are the actual MAPs for the year 2013/2014, not hypothetical MAPs by way of illustration.

- The eighth paragraph of section 2 of the framework puts beyond doubt that this interpretation is correct. It reads:

"The amount of profit due in each work type will be calculated by inputting the performance figures into the KPI matrix as set out in the example below. This calculates exactly where the performance is on the range of scores between the minimum acceptable standard, the target and beyond."

It is obvious that only the performance figures in the "examples" are hypothetical. The other columns state or re-state the contractual provisions or the arithmetical consequences of those provisions.

- Ms Stephens submits that even if that analysis is correct, it only applies to the year 2013/2014. Neither the "examples" nor any other provisions in the framework specify the MAPs for 2014/2015.

- Once again, if that is right, the consequences would be extraordinary. Rydon would receive all due bonuses in year one. Then at the start of year two they would cease to be entitled to any bonuses. Sutton would be similarly prejudiced. They could terminate under clause 12.1.9 in conjunction with clause 13.1 in year one, but not in year two. That would, with all due respect, be an absurdity, which no-one could have intended.

- The three examples make it abundantly clear that in every instance the MAP is 3 % lower than the target figure. That is obviously the ratio which the parties intended and agreed. Accordingly the MAPs for 2014/2015 must be 3% lower than the target figures set out in paragraph 5 of the framework. Therefore the agreed MAPs for 2014/2015 must be:

| AM.SI.10 |

96% |

| AM.SI.11 |

94% |

| AM.SI.12 |

93% |

| AM.SI.29 |

93% |

| AM.SI.13 |

94% |

| AM.SI.14 |

93% |

| Appointments kept for non-communal repairs |

93% |

- That is the only rational interpretation of the curious contractual provisions into which the parties have entered. In my view, therefore, we should allow this appeal and grant a declaration as sought by Sutton. No doubt counsel will agree the appropriate wording.

Lord Justice Beatson:

- I agree.

APPENDIX

Example 1

All KPIs exceed target

Example 2

All KPIs fail to meet PPT

Example 3

Some KPIs meet or exceed target

Some KPI exceed PPT but do not meet target

BAILII:

Copyright Policy |

Disclaimers |

Privacy Policy |

Feedback |

Donate to BAILII

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2017/359.html