Upper Tribunal

(Immigration and Asylum Chamber)

AS (Safety of Kabul) Afghanistan CG [2018] UKUT 118 (IAC)

THE IMMIGRATION ACTS

|

Heard at Field House

|

Decision & Reasons Promulgated

|

|

On 25th & 27th September; 24th

October;

20th November and 11th December

2017

|

|

|

|

…………………………………

|

Before

UPPER TRIBUNAL JUDGE ALLEN

UPPER TRIBUNAL JUDGE JACKSON

Between

as

(ANONYMITY

DIRECTION MADE)

Appellant

and

THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME

DEPARTMENT

Respondent

Representation:

For the Appellant: Ms S Naik

QC, Ms B Poynor and Mr B Bundock of Counsel, instructed by J D Spicer Zeb

solicitors

For the Respondent: Mr S Singh QC,

instructed by the Government Legal Department

COUNTRY GUIDANCE

Risk on return to Kabul from the

Taliban

(i)

A person who is

of lower-level interest for the Taliban (i.e. not a senior government or

security services official, or a spy) is not at real risk of persecution from

the Taliban in Kabul.

Internal relocation to Kabul

(ii)

Having regard

to the security and humanitarian situation in Kabul as well as the difficulties

faced by the population living there (primarily the urban poor but also IDPs

and other returnees, which are not dissimilar to the conditions faced

throughout may other parts of Afghanistan); it will not, in general be unreasonable

or unduly harsh for a single adult male in good health to relocate to Kabul

even if he does not have any specific connections or support network in Kabul.

(iii)

However, the

particular circumstances of an individual applicant must be taken into account

in the context of conditions in the place of relocation, including a person’s

age, nature and quality of support network/connections with Kabul/Afghanistan,

their physical and mental health, and their language, education and vocational

skills when determining whether a person falls within the general position set

out above.

(iv)

A person with a

support network or specific connections in Kabul is likely to be in a more

advantageous position on return, which may counter a particular vulnerability

of an individual on return.

(v)

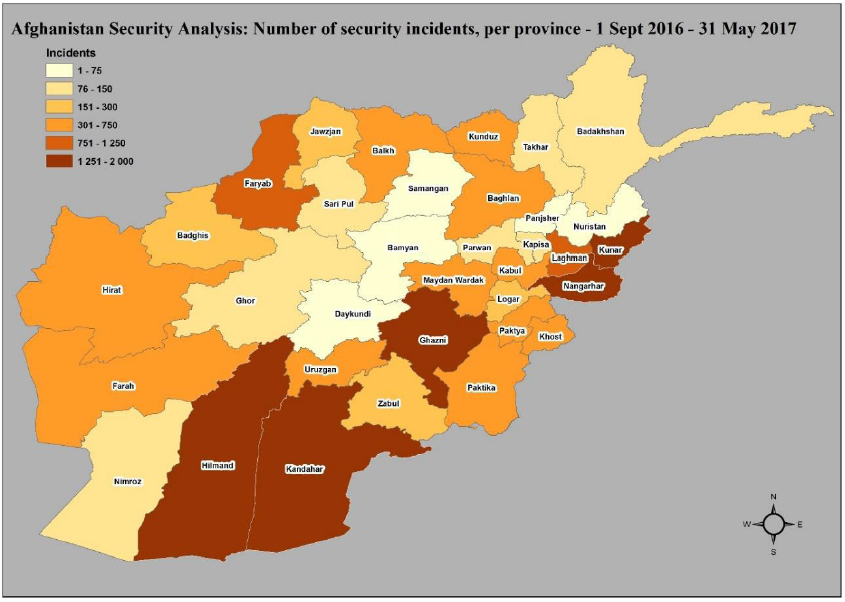

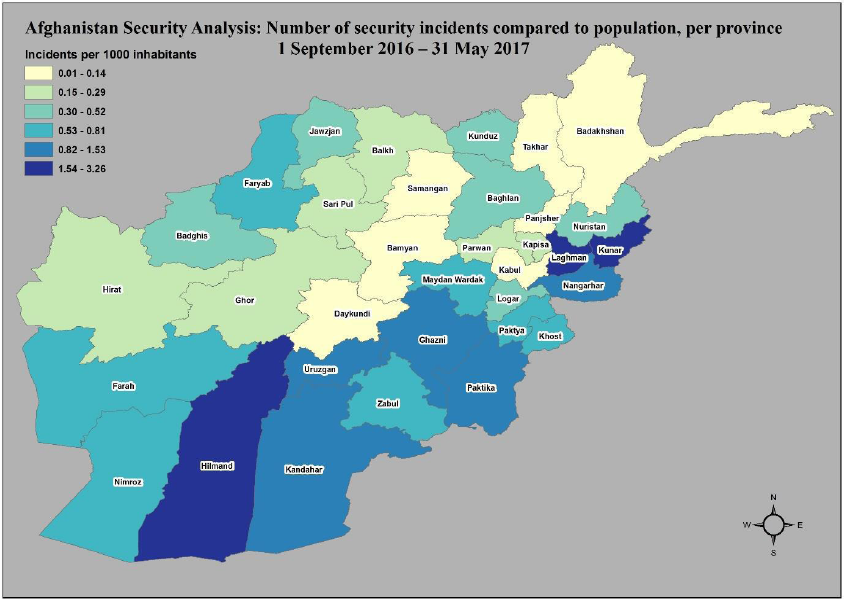

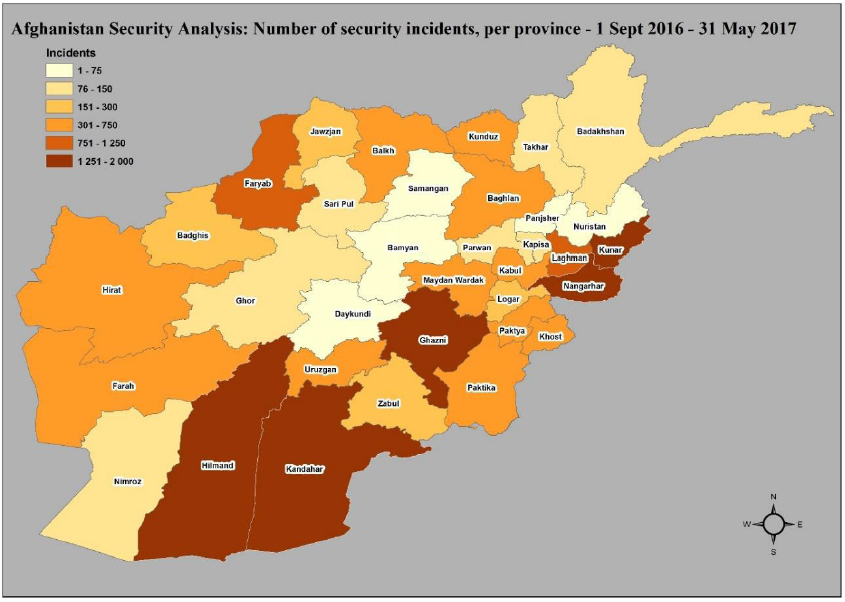

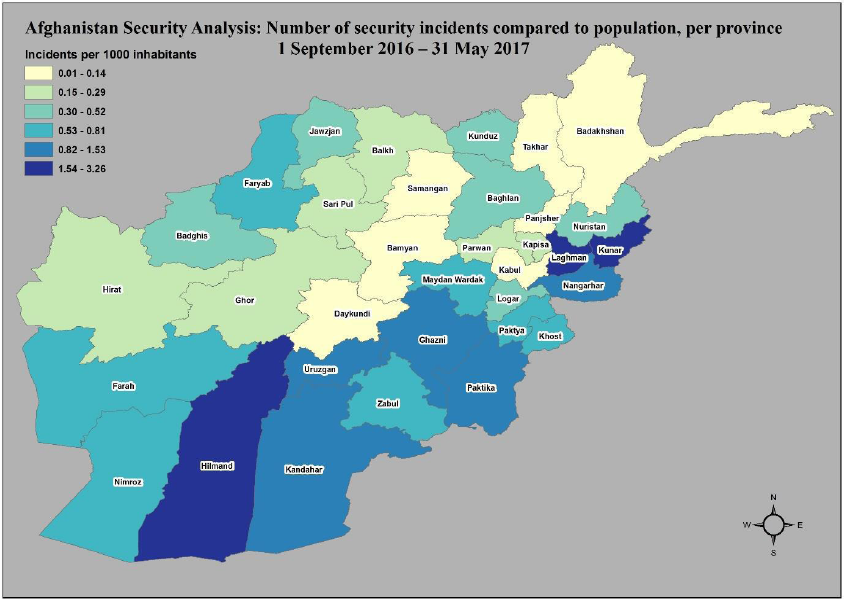

Although Kabul suffered the highest number of civilian casualties (in the latest UNAMA figures from

2017) and the number of security incidents is increasing, the proportion of the

population directly affected by the security situation is tiny. The current

security situation in Kabul is not at such a level as to render internal

relocation unreasonable or unduly harsh.

Previous Country Guidance

(vi)

The country

guidance in AK (Article 15(c)) Afghanistan CG [2012] UKUT 163 (IAC) in

relation to Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive remains unaffected by

this decision.

(vii)

The country

guidance in AK (Article 15(c)) Afghanistan CG [2012] UKUT 163 (IAC) in

relation to the (un)reasonableness of internal relocation to Kabul (and other

potential places of internal relocation) for certain categories of women

remains unaffected by this decision.

(viii) The country guidance in AA

(unattended children) Afghanistan CG [2012] UKUT 16 (IAC) also remains

unaffected by this decision.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

Description

|

Paragraphs

|

|

Introduction

|

1-4

|

|

The Country Guidance Question

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

The Appeal

|

5-13

|

|

|

|

|

The Legal Framework

|

14-44

|

|

Burden of Proof

|

41-44

|

|

|

|

|

The Evidence

|

45-171

|

|

The Experts

|

47-66

|

|

Evidence on risk

|

67-97

|

|

Internal Relocation

|

98-154

|

|

Returns

|

155-171

|

|

|

|

|

Findings and Reasons

|

172- 252

|

|

Risk

|

173-188

|

|

Reasonableness

|

189-235

|

|

Previous Country

Guidance

|

236-240

|

|

Summary of general

conclusions

|

241

|

|

The Appellant’s claim

|

242 -252

|

|

|

|

|

Notice of Decision

|

Notice

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix A

|

A

|

|

Schedule of Background

and Expert Evidence considered by the Tribunal

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix B

|

B

|

|

Extract from

EASO Country of Origin Information Report, Afghanistan: Security Situation”

(August 2017).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix C

|

C

|

|

Error of Law Decision

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix D

|

D

|

|

Senior President’s

Practice Direction No 10 (2010)

|

|

GLOSSARY

|

AMASO

|

- Afghanistan Migrants Advice and

Support Organisation

|

|

AAN

|

- Afghan Analysts

Network

|

|

AGEF

|

- Experts in the Fields

of Migration and Development

|

|

AGEs

|

- Anti-government

elements

|

|

AVRR

|

- Assisted Voluntary

Return and Reintegration

|

|

DTM

|

- Displacement tracking

matrix

|

|

EASO

|

- European Asylum

Support Office

|

|

ERIN

|

- European Reintegration

Network

|

|

GBV

|

- Gender based violence

|

|

GDP

|

- Gross domestic product

|

|

HRW

|

- Human Rights Watch

|

|

IDPs

|

- Internally displaced

persons

|

|

IEDs

|

- Improvised explosive

devices

|

|

IOM

|

- International

Organisation for Migration

|

|

IPSO

|

- International

Psychosocial Organisation

|

|

IRA/IFA

|

- Internal relocation

alternative/Internal flight alternative

|

|

ISKP

|

- Islamic State of the Khorasan

Province

|

|

NGOs

|

- Non-governmental organisations

|

|

UN

|

- United Nations

|

|

UNAMA

|

- UN Assistant Mission in Afghanistan

|

|

UNFPA

|

- UN Population Fund

|

|

UNHCR

|

- UN High Commissioner

for Refugees

|

|

UNOCHA

|

- UN Office for

Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

|

DECISION AND REASONS

Introduction

1.

The question posed

by the Upper Tribunal for country guidance in this case is:

“Whether the current situation in Kabul

is such that the guidance given in AK (Afghanistan) [2012] UKUT 163 (IAC)

needs revision in the context of consideration of internal relocation.”

2.

The guidance in AK

on this point at B is as follows:

“(iv) Whilst when assessing a claim in

the context of Article 15(c) in which the respondent asserts that Kabul city

would be a viable internal relocation alternative, it is necessary to take into

account (both in assessing “safety” and “reasonableness”) not only the level of

violence in that city but also the difficulties experienced by that city’s poor

and also the many Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) living there, these

considerations will not in general make return to Kabul unsafe or unreasonable.

(v) Nevertheless, this position is

qualified (both in relation to Kabul and other potential places of internal

relocation) for certain categories of women. The purport of the current Home

Office OGN on Afghanistan is that whilst women with a male support network may

be able to relocate internally, “… it would be unreasonable to expect lone

women and female heads of household to relocate internally” (February 2012 OGN,

3.10.8) and the Tribunal sees no basis for taking a different view.”

3.

Also important in

the specific context of the question posed in the present country guidance case

are the fuller findings in paragraph 243 of AK, which appear immediately

prior to the conclusion set out in (iv) above:

“As regards Kabul city, we have

already discussed the situation in that city and we cannot see that for the

purposes of deciding either refugee eligibility or subsidiary protection

eligibility (and we are only formally tasked with deciding the latter) that

conditions in that city make relocation there in general unreasonable, whether

considered under Article 15(c) or under 15(b) or 15(a). We emphasise the words

“in general” because it is plain from Article 8(2) and our domestic case law on

internal relocation (see AH (Sudan) in particular) that in every case

there needs to be an enquiry into the applicant’s individual circumstances; and

what those circumstances are will very often depend on the nature of specific

findings made about the credibility of an appellant in respect of such matters

as whether they have family ties in Kabul. But here our premise concerns an

appellant with no specific risk characteristics and someone found to have an

uncle in Kabul: see above paras 3, 5, 154, 186 and below, paras 250-254). …”

4.

When considering

the question posed for the present case, we bear in mind that the focus in AK

was on Article 15(c) of Council Directive 2004/83/EC of 29 April 2004 on

Minimum Standards for the Qualification and Status of Third Country Nationals or

Stateless Persons as Refugees or as Persons Who Otherwise Need International

Protection and the Content of the Protection Granted (the “Qualification

Directive”) and eligibility for subsidiary protection, rather than the issue of

internal relocation in the context of the Refugee Convention and that the

evidence before that panel on the socio-economic conditions in Kabul was

relatively limited compared to what is before us in the present appeal. We

also bear in mind that the decision in AK was based principally on

evidence from 2010 to 2011 and on any view, there have been rapid and

significant changes in both Kabul and Afghanistan as a whole in the intervening

period.

The Appeal

5.

The Appellant, a

national of Afghanistan born on 1 January 1986, appealed the Respondent’s

decision dated 12 February 2015 to refuse his asylum and human rights claim.

His appeal was dismissed by First-tier Tribunal Judge Bradshaw in a

determination promulgated on 30 July 2015. Although Judge Bradshaw accepted

that the Appellant would be at risk on return to his home area from the

Taliban, his asylum appeal was dismissed on the basis that he could internally

relocate to Kabul. The Appellant’s human rights appeal was dismissed on the

basis that there would be no disproportionate interference with the Appellant’s

right to respect for private and family life contrary to Article 8 of the

European Convention on Human Rights.

6.

The Appellant

sought permission to appeal on two grounds, first, that the Judge failed to properly

consider submissions made to him on Article 15(c) of the Qualification

Directive and secondly, that she failed to properly consider the evidence in

relation to internal relocation. Permission was granted on both grounds by UTJ

Taylor on 2 October 2015. At an early stage, the appeal was identified as

possible country guidance.

7.

In his decision

promulgated following a hearing on 27 April 2017 (Appendix C) UTJ O’Connor

found an error of law such that it was necessary to set aside the decision of

Judge Bradshaw. In so finding, he stated that “The findings of primary fact

made by the First-tier Tribunal have not been the subject of challenge and are

preserved, as is the conclusion that the Appellant would be at risk of

suffering persecutory treatment in his home area.” In addition, the finding

that the Appellant is not at risk on return to his home area or elsewhere from

the Afghan government has not been challenged and stands.

8.

For the purposes

of the present appeal and, in particular, the letter of instruction to the

experts, the following are agreed facts.

a)

The Appellant (dob

1 January 1986) is a single man from Kardai village, Laghman province, Afghanistan. He is thus 31 years of age.

b) The Appellant’s father was the imam of

the local mosque and well-known in the village, where the Taliban have a

presence. He refused to cooperate with them or propagate for them and was

labelled a government agent. In 2006 the Taliban killed him.

c)

The Appellant’s

brother reported their father’s murder to the authorities and 10 days later

there was an attack on the local Taliban by government forces. The Taliban

suspected the Appellant’s brother of spying for the government and killed him

in 2007.

d) Sometime later the Taliban abducted

the Appellant from his house and detained him away from the village along with

others. While detained, he was not fingerprinted or photographed by the

Taliban. A week later, the Appellant escaped during a night raid by government

forces and returned to Kardai village, whereupon his maternal uncle passed him

to a friend and then to an agent to take him out of Afghanistan.

e)

The Appellant fled

Afghanistan clandestinely in 2008 and entered the United Kingdom towards the

end of that year, having passed through other countries en route. The

Appellant’s mother, younger brother and maternal uncle remained in Kardai

village.

f)

The Appellant

would be at risk of persecution if returned to his local area.

9.

For the purposes

of instructions to the experts, there were a number of facts which they were

asked to assume although they were not agreed aspects of the Appellant’s

account between the parties. These included the Appellant’s claim that when in

Afghanistan he attended school for nine years and thereafter worked with his

brother in farming; that he has not had contact with his mother, younger

brother and maternal uncle since arriving in the United Kingdom; and that the

Appellant has no family or support in Kabul.

10.

In summary, the

Appellant’s case is that he is at risk from the Taliban in his home area and

also in Kabul, where there would be no sufficiency of protection from such

risk. In any event, internal relocation to Kabul is not reasonable because he

is at risk of harm (kidnapping/extortion of money) on account of his

westernised profile; because he has no family or other support network in Kabul

to assist him in obtaining accommodation and/or employment; because he is at

risk of being in conditions comparable to those of an IDP (with greater risk of

unemployment, limited access to adequate housing, limited access to water and

sanitation and food insecurity) and that reintegration assistance will not

relieve these issues.

11.

It is important to

note at the outset that it is not the Appellant’s case that treatment in Kabul

would be in breach of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights or

Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive.

12.

In summary, the

Respondent’s case is that although the Appellant would be at risk of

persecution if returned to his local area in Afghanistan, he would be able to

safely and reasonably internally relocate to Kabul and for this reason is not

entitled to be recognised as a refugee under the Refugee Convention nor be

granted humanitarian protection.

13.

It is important to

note at the outset, that the Respondent does not rely on there being a sufficiency

of protection for the Appellant from the Taliban in Afghanistan, or in

particular in areas where he is accepted to be at risk. The Respondent

acknowledges that however willing the Afghan authorities are, they would

usually be unable to offer effective protection. For this reason, we do not in

this decision, set out in any detail the substantial evidence before us on the

capacity of the Afghan forces, issues of corruption and human rights abuses

within them, nor do we set out evidence before us on the judiciary in Afghanistan.

Legal framework

14.

By Article 1A(2)

of the Refugee Convention, a refugee is a person who is out of the country of

his or her nationality and who, owing to a well-founded fear of persecution for

reasons of race, religion, nationality or membership of a particular social

group or political opinion, is unable or unwilling to avail him or herself of

the protection of the country of origin.

15.

Article 8 of the

Qualification Directive provides as follows:

1. As part of the assessment of the

application for international protection, Member States may determine that an

applicant is not in need of international protection if in a part of the

country of origin there is no well-founded fear of being persecuted or no real risk

of suffering serious harm and the applicant can reasonably be expected to stay

in that part of the country.

2. In examining whether a part of the

country of origin is in accordance with paragraph 1, Member States shall at the

time of taking the decision on the application have regard to the general

circumstances prevailing in that part of the country and to the personal

circumstances of the applicant.

3. Paragraph 1 may apply notwithstanding

technical obstacles to return to the country of origin.

16.

The Immigration

Rules provide in Rule 339O(i):

(i) The Secretary of State will not

make:

(a) a grant of refugee status if in

part of the country of origin a person would not have a well founded fear of

being persecuted, and the person can reasonably be expected to stay in that

part of the country; or

(b) a grant of humanitarian protection

if in part of the country of return a person would not face a real risk of

suffering serious harm, and the person can reasonably be expected to stay in

that part of the country.

(ii) In examining

whether a part of the country of origin or country of return meets the

requirements in (i) the Secretary of State, when making a decision on whether

to grant asylum or humanitarian protection, will have regard to the general

circumstances prevailing in that part of the country and to the personal

circumstances of the person.

(iii) (i) applies

notwithstanding technical obstacles to return to the country of origin or

country of return.

17.

From the above, a

person is not a refugee if they can reasonably be expected to live in another

part of their home country where they would not have a well-founded fear of

persecution. In such circumstances, a person has the option of internal

relocation, also known as an internal flight alternative. Once the issue of

internal relocation has been raised there are two discrete questions to

determine whether there is an option of internal relocation. First, does the

person have a well-founded fear of persecution in the proposed place of

relocation? If yes, then there is no internal relocation option and the person

is a refugee. There is also no internal relocation option if the person would

be subject to inhuman or degrading treatment within the meaning of Article 3 of

the European Convention on Human Rights (the “ECHR”) in the proposed place of

relocation or if it would be in breach of Article 15(c) of the Qualification

Directive. If not, then secondly there must be an assessment of whether in all

the circumstances, it would be reasonable or not unduly harsh to expect the

person to relocate to that place.

18.

Lord Bingham

summarised the approach to reasonableness in Januzi v Secretary of State for

the Home Department [2006] 2 AC 426, at [21]:

“The decision-maker, taking account of

all relevant circumstances pertaining to the claimant and his country of

origin, must decide whether it is reasonable to expect the claimant to relocate

or whether it would be unduly harsh to expect him to do so… There is, as Simon

Brown LJ aptly observed in Svazas v Secretary of State for the Home

Department [2002] 1 WLR 1891, para 55, a spectrum of cases. The

decision-maker must do his best to decide, on such material as is available,

where on the spectrum the particular case falls… All must depend on a fair

assessment of the relevant facts.”

19.

Further, at [47],

Lord Hope stated the position as follows:

“The question where the issue of

internal relocation is raised can, then, be defined quite simply … it is

whether it would be unduly harsh to expect a claimant who is being persecuted for

a Convention reason in one part of his country to move to a less hostile part

before seeking refugee status abroad. The words “unduly harsh” set the

standard that must be met for this to be regarded as unreasonable. If the

claimant can live a relatively normal life there by the standards that prevail

in his country of nationality generally, and if he can reach the less hostile

part without undue hardship or undue difficulty, it will not be unreasonable to

expect him to move there.”

20.

The test was

considered further by the House of Lords in AH (Sudan) v Secretary of State

for the Home Department [2008] 1 AC 678, upon which we had detailed

submissions from the parties as to the scope of the test of reasonableness of

internal relocation. We therefore set out more fully the judgements in that

case and the principles which flow from it, not all of which were controversial

between the parties.

21.

First, Lord

Bingham, having referred to his own judgement at [21] of Januzi, (set

out above), went on to say at [5]:

“Although specifically directed to a

secondary issue in the case, these observations are plainly of general

application. It is not easy to see how the rule could be more simply or

clearly expressed. It is, or should be, evident that the enquiry must be directed

to the situation of the particular applicant, whose age, gender, experience,

health, skills and family ties may all be very relevant. There is no warrant

for excluding, giving priority to, consideration of the applicant’s way of life

in the place of persecution. There is no warrant for excluding, or giving

priority to, consideration of conditions generally prevailing in the home

country. I do not estimate the difficulty of making decisions in some cases. But

the difficulty lies in applying the test, not in expressing it. The

humanitarian object of the Refugee Convention is to secure a reasonable measure

of protection for those with a well-founded fear of persecution in their home

country or some part of it; it is not to procure general levelling-up of living

standards around the world, desirable though of course that is.”

22.

Baroness Hale confirmed

at [20] that the House was all agreed that the correct approach was that set

out by Lord Bingham in Januzi and further endorsed the following

submission from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) of

the correct approach:

“The correct approach when considering

the reasonableness of IRA [internal relocation alternative] is to assess all

the circumstances of the individual’s case holistically and with specific

reference to the individual’s personal circumstances (including past

persecution or fear thereof, psychological and health condition, family and

social situation, and survival capacities). This assessment is to be made in

the context of the conditions in the place of relocation (including basic human

rights, security conditions, socio-economic conditions, accommodation, access

to health care facilities), in order to determine the impact on that individual

of settling in the proposed place of relocation and whether the individual

could live a relatively normal life without undue hardship.”

23.

The assessment

must therefore consider the particular circumstances of the individual

applicant in the context of conditions in the place of relocation. The test of

reasonableness is one of great generality, excluding only a comparison with

conditions in the host country in which protection has been sought, per Lord

Bingham at [13] and Baroness Hale at [27].

24.

Secondly, the test

of reasonableness is not analogous to, or to be equated with, the test under

Article 3 of the ECHR, per Lord Bingham at [9] and Baroness Hale at [21-22 and

26]. If, however, conditions in the proposed place of relocation do breach

Article 3 of the ECHR, internal relocation would automatically be unreasonable

without more.

25.

Thirdly, the

correct comparator by which to judge reasonableness is not against the

conditions for the worst of the worst in that country. Put another way, it is

not a consideration of whether a person’s circumstances will be worse than the circumstances

of anyone else in that country, per Baroness Hale at [27-28].

26.

Finally, Lord

Brown, who expressly agrees with the opinion of Lord Bingham (and both of whom

are expressly agreed with by Lord Hope at [18]), expanded upon the test of

reasonableness at [42] as follows:

“As mentioned, one touchstone of

whether relocation would involve undue hardship, identified in the UNHCR

guidelines referred to in the passage already cited from para 47 of Lord Hope’s

speech in Januzi, is whether “in the context of the country concerned”

the claimant can live “a relatively normal life”. The respondents are fiercely

critical of the Tribunal’s approach to this question in the present case. In

particular they criticise the Tribunal’s conclusion as to “the subsistence

level existence in which people in Sudan generally live”. To my mind, however,

this criticism is misplaced. It is not necessary to establish that a majority

of the population live at subsistence level for that to be regarded as a

“relatively normal” existence in the country as a whole. If a significant

minority suffer equivalent hardship to that likely to be suffered by claimant

on relocation and if the claimant is as well able to bear it as most, it may

well be appropriate to refuse him international protection. Hard-hearted as

this may sound, and sympathetic although one inevitably feels towards those who

have suffered as have these respondents (and the tens of thousands like them),

the Refugee Convention, as I have sought to explain, is really intended only to

protect those threatened with specific forms of persecution. It is not a

general humanitarian measure. For these respondents, persecution is no longer

a risk. Given that they can now safely be returned home, only prove that their

lives on return would be quite simply intolerable compared even to the problems

and deprivations of so many of their fellow countrymen would entitle them to

refugee status. Compassion alone cannot justify the grant of asylum.”

27.

It is the

Respondent’s reliance on this last paragraph at [42] of Lord Brown’s speech, in

particular, the reference to a significant minority of the population, that the

Appellant took significant issue with during the course of the hearing before

us for the following reasons. First, it was submitted that this could not be

relied upon because it was an obiter dicta comment (because in fact the

conditions considered in Sudan were those of the majority of the population),

expressed in a minority judgement (not expressly endorsed by Lord Bingham,

Baroness Hale or Lord Hoffmann) and therefore not binding upon the Upper

tribunal.

28.

Secondly, there

has been no application of the proposition of a comparison with a significant

minority of the population in any Court or Tribunal since AH (Sudan).

29.

Thirdly, the

proposition was inconsistent with the ratio in AH (Sudan) as

articulated by Lord Bingham, with whom all agreed, which was to expressly

approve of the test set out in Januzi without excluding or giving priority

to consideration of the applicant’s way of life in the place of persecution or

the conditions generally prevailing in the home country.

30.

Fourthly, the

proposition is also inconsistent with the judgement of Baroness Hale in AH (Sudan) as it would inevitably lead to a comparison with the very worst lives led by

fellow nationals.

31.

Fifthly, it is

inconsistent with the UNHCR guidelines which were endorsed by Lord Bingham in Januzi

as giving “valuable guidance” on a proper approach to assessing

reasonableness.

32.

Sixthly, it is

inconsistent with the ratio of the Court of Appeal in AA (Uganda) v

Secretary of State for the Home Department [2008] EWCA Civ 579,

specifically with the judgment of Buxton LJ who referred to some conditions in

the place of relocation as being unacceptable even if widespread in that

place.

33.

Finally, the

proposition is inconsistent with the decision of the Upper Tribunal in FB

(Lone Women – PSG – internal relocation – AA (Uganda) considered) Sierra Leone

[2008] UKAIT 00090, in which it was reiterated that there are some forms or

degrees of hardship which will be unduly harsh irrespective of how many others

endure them.

34.

In response, Mr

Singh relied upon the fact that Lord Brown’s speech in AH (Sudan) had

been expressly approved by Lord Hope and also by Buxton LJ in AA (Uganda),

who described Lord Browne’s judgment at [42] “valuably explain[ing] some

further aspects of the jurisprudence of undue harshness”.

35.

As to what a

significant minority would be, it was submitted by Mr Singh that significant

minority was simply something sufficiently great in number to be worthy of

attention and the opposite to insignificant. In reality, he submitted that the

population of Kabul is a significant minority of the population in Afghanistan

and even a significant minority of the population of Kabul itself could still

amount to a significant minority of the population of Afghanistan

as a whole.

36.

We do not consider

that Lord Brown’s judgment in AH (Sudan) is either strictly obiter

dicta or a minority judgment such that it is not binding on the Upper

Tribunal. This is because first, it was expressly approved by Lord Hope;

secondly, it is not inconsistent with the speeches of Lord Bingham or Baroness

Hale in AH (Sudan); and thirdly, in any event it was expressly approved

by Buxton LJ in AA (Uganda) which is itself binding on us.

37.

When assessing the

reasonableness of internal relocation, the language used in Januzi and AH

(Sudan) is of standards or conditions generally prevailing in the home

country and of whether a person can live a relatively normal life. There is of

course no single standard or set of conditions which apply throughout a

country, but a range of examples of ‘normal’ or conditions which are

experienced either in particular parts of the country, or throughout it by groups

of people. One can envisage for example, that there will almost inevitably in

any country in the world be differences between standards generally prevailing

in urban as opposed to rural areas, and between the capital or large cities and

other areas. That is not to say that because the majority of the population

live in, for example a rural area, the conditions in urban areas could not said

to be normal or include conditions generally prevailing in the home country.

We consider that Lord Brown’s reference to a significant minority of the

population is expanding on what is contained in the speeches of Lord Bingham

and Baroness Hale, and is simply a way of expressing what is, in practice,

required to identify standards or conditions generally prevailing in the home

country, reflecting that there is not a single standard or set of conditions

which apply to a simple numerical majority of the population throughout the

entire geographical territory of a country.

38.

In support of

this, we rely on what was said by Buxton LJ in AA Uganda, which

expressly endorses Lord Brown’s speech, including the significant minority

point at his [42]:

“16. Whilst Immigration Judge Coker

did not have the benefit of the House of Lords in AH (Sudan) she clearly

had the jurisprudence that their Lordships confirmed in mind when she said, at

the end of her §38, that the situation facing AA was the same as that of many

other young women living in Kampala, and quoted Lord Hope of Craighead, who

asked whether the claimant could live a relatively normal life judged by the

standards that prevail in his country of nationality generally: those

standards, or the relevant hardship, being as Lord Brown of Eaton-under-Haywood

explained in AH (Sudan) that of a significant minority in the country.

The evidence before the AIT in this case did not reveal how widespread in the

context of Uganda as a whole are the conditions reported by Dr Nelson, and did

not suggest that they affect anyone other than young women. The factual case is

therefore significantly different from that in AH (Sudan)

where slum conditions were widespread in Sudan, and affected everyone, men

women and children alike, and of all ages. Immigration Judge Coker should

therefore have considered whether it was appropriate to apply the test

formulated by Lord Hope of Craighead to a case where the comparator or

constituency in the place of relocation is limited to persons who suffer from

the same specific characteristics that expose the applicant to danger and

hardship in the place of relocation.

17. There is, however, a further and

more fundamental reason why it is difficult or impossible to apply the

jurisprudence of AH (Sudan) to the present case. There, the conditions

in the place of relocation included poverty, disease and the living of a life

that was structured quite differently from that from which the appellants had

come in Darfur. It had been open to the AIT to hold that exposure to those

conditions, shared by many of the refugees’ fellow-countrymen, did not amount

to undue harshness. But the present case is different. On the evidence

accepted by the AIT, AA is faced not merely with poverty and lack of any sort

of accommodation, but with being driven into prostitution. Even if that is the

likely fate of many of her fellow countrywomen, I cannot think that either the

AIT or the House of Lords that decided AH (Sudan) would have felt able

to regard enforced prostitution as coming within the category of normal country

conditions that the refugee must be expected to put up with. Quite simply,

there must be some conditions in the place of relocation that are unacceptable

to the extent that it would be unduly harsh to return the applicant to them

even if the conditions are widespread in the place of relocation.”

39.

The test, or

comparator for the purposes of assessing reasonableness, is as set out in AH

(Sudan), including as expressly set out by Lord Brown, with the caveat that

there are some conditions that are unacceptable even if widely suffered in the

place of relocation. That particular point was confirmed and expanded upon by

the Upper Tribunal in FB (Lone women – PSG – internal relocation – AA

(Uganda) considered) Sierra Leone [2008] UKAIT 00090, which held at [39]

that “[AA (Uganda)] is affirmation, in line with AH (Sudan)

that [internal] relocation must be reasonable, in other words, that it must not

have such consequences upon the individual as to be unduly harsh for her.

Inevitably, it will be unduly harsh if an appellant is unable for all practical

purposes to survive with sufficient dignity to reflect her humanity. That is

no more than saying that if survival comes at a cost of destitution, beggary,

crime or prostitution, then that is a price too high.”

40.

The final

principle that therefore flows from AH (Sudan) is that when considering

the standards or conditions prevailing generally in the country of nationality,

it is not necessary to establish that a majority of the population live in

those particular conditions, but only that a significant minority suffer

equivalent hardship to that likely to be suffered by the applicant on

relocation. What follows is then a personalised assessment of whether the

applicant would be as well able to bear it ia most or whether those conditions

are in any event unreasonable, for example because they involve crime,

destitution, prostitution and the like. There is no requirement for a specific

numerical, geographical or other qualification on what is a significant

minority of the population. That phrase carries its ordinary and natural

meaning of something of a sufficiently great number to be worthy of attention

in the context of the population of the home country and not insignificant and

its application should be self-evident on an assessment of the factual evidence

in the majority if not all cases. If interpreted this way, there is no central

inconsistency with Baroness Hale’s speech in AH (Sudan) which

highlighted, inter alia, the concern that the comparator should not be with the

poorest of the poor in a particular country.

Burden of Proof

41.

The burden of

proof is on the Appellant to establish that he is a refugee. The degree of

likelihood of persecution needed to establish an entitlement to asylum is

decided on a basis lower than the civil standard of the balance of probabilities.

This is expressed as a “reasonable chance”, “a serious possibility” or

“substantial grounds for thinking” in the various authorities. That standard of

probability not only applies to the history of the matter and to the situation

at the date of decision, but also to the question of persecution in the future

if the Appellant were to be returned.

42.

We received

submissions from both parties as to the correct burden of proof on the test of

reasonableness for internal relocation. On behalf of the Appellant it was

submitted that in accordance with the UNHCR guidelines and the Michigan

Guidelines on “The Internal Protection Alternative”, the burden is on the

decision-maker (both the Respondent and the First-tier Tribunal/Upper Tribunal)

or in the alternative that there was a shared burden between an applicant and

the Respondent.

43.

On behalf of the

Respondent, Counsel relied on the Upper Tribunal’s decision in AMM and

others (conflict: humanitarian crisis; returnees; FGM) Somalia

CG [2011] UKUT 445 (IAC), that where the issue of internal relocation is

raised, an applicant must make good on the submission that relocation would not

be reasonable.

44.

As confirmed most

recently by the Senior President of the Tribunals in Secretary of State for

the Home Department v SC (Jamaica) [2017] EWCA Civ 2112 (handed down after

the hearing in the present appeal), at 36, there is no burden of proof in

relation to the overall issue of whether it is reasonable for a person to

internally relocate.

Evidence

45.

We begin by identifying

the experts who submitted written evidence and gave oral evidence before us,

setting out their relevant areas of expertise and our overall impressions of

that evidence in general terms, including as to the weight to be attached to

their evidence generally.

46.

We go on to

consider below the evidence before us, both written and oral, first as to risk

on return to Kabul and secondly as to safety and reasonableness of internal

relocation by setting out the current situation in Kabul in particular, but also

in relation to Afghanistan more widely. In line with the legal framework set

out above, we undertake a holistic assessment of the conditions generally

prevailing in Afghanistan to assess the reasonableness of internal relocation,

but for practical reasons we separate out and very broadly summarise the

evidence in relation to particular topics sequentially which contribute to the

holistic assessment. The full list of evidence before the Upper Tribunal in

this appeal is set out in Appendix B which has been considered by us in its

entirety and the absence of any express reference to it in the summary included

(which is of necessity a brief summary) should not be taken as an indication

that a particular piece of evidence or part of it has not been taken into

account when reaching our conclusions set out below.

The Experts

47.

Three experts were

instructed, each of whom submitted written reports and gave oral evidence

before us, on the basis of joint written instructions. Further to receipt of

the written reports from each expert, the Respondent asked further questions of

each expert which were responded to by way of supplementary written reports.

We set out initially our overview of the experts and their evidence and go on

to consider later the detail of that evidence by topic.

48.

Dr Liza Schuster

is a Reader in the Department of Sociology at the University of London

and has been employed as a researcher at both the University of Oxford

and the London School of Economics. She has visited and lived in Afghanistan

for significant periods of time since 2011 (totalling around five years),

during which she has lived with Afghan families and in different settings in Kabul.

Dr Schuster is one of less than a dozen non-Afghans who live and work doing

research in this field in Kabul. Since November 2016, Dr Schuster has been

based in Kabul undertaking a research project studying migration decisions,

policy-making and migration culture based at the university there.

49.

Of particular

relevance for this appeal, Dr Schuster has conducted research in Afghanistan since 2012 as to the consequences of forced return for Afghan migrants and

their families and the migration decision-making process. This involved a

number of in-depth interviews with individuals and their families. In the

initial project, she interviewed 32 young men who had been deported and the

families of 12 others in Kabul and Pule Khumri. In total, Dr Schuster has

spoken to approximately 120 people who have been returned to Kabul against

their will from EU states. She remains in touch with 12 of them, all of whom

are no longer in Afghanistan.

50.

In 2014, Dr

Schuster set up the Afghanistan Migrants Advice and Support Organisation (AMASO)

with Abdul Ghafoor, an Afghan man who was forcibly returned to Afghanistan

following a failed application for asylum in Norway. AMASO was initially

supported by money from Norway to support others on return, for example by

accessing IOM packages and providing advice to those who didn’t understand what

was happening. Dr Schuster trained Mr Ghafoor and provided initial funding,

but he now runs the organisation himself, funded from external grants. AMASO

provides information to those returned to Afghanistan and to those wishing to

leave the country, explaining processes to them, options and support available,

helping to channel support and occasionally facilitating skype or

video-conferencing for out of country appeals. It also provides limited

accommodation for up to 10 men in Kabul.

51.

In the last three

years, Abdul Ghafoor has been contacted by more than 300 individuals and Dr

Schuster remains in contact with him to discuss cases. Of that number, he has

interviewed 180 people and Dr Schuster was present for about 40 of those

interviews. Of those 300 people, they have lost touch with 75, about 65 have

left Afghanistan and 40 remain in Afghanistan, of which 20 are in Kabul.

52.

At present, Dr

Schuster is following 18 families after return to Afghanistan, which includes a

range of ethnic tribes, people from both Kabul and the provinces, and a mix of

people from different income groups and family sizes. The project is looking

at their plans, hopes and fears for the future.

53.

Dr Schuster was

specifically asked about living conditions and economic survival in Kabul

and the present humanitarian situation. In particular, she was asked to

consider sources of independent support; employment

opportunities; levels of subsistence; destitution; shelter/accommodation and

accessible amenities; and availability of healthcare; as well as the situation

for IDPs. Dr Schuster’s report was based in part on fieldwork with those who

have been returned or their families and in part informed by first-hand

experience of time in the country, hearing comments, concerns and questions

from Afghans.

54.

Overall, we found

Dr Schuster’s evidence to be clear, comprehensive, well-researched from both

written sources and contacts in Afghanistan and based on her own in-depth

experience from living in Afghanistan, working with those who have been

returned there and through AMASO. We attach significant weight to Dr

Schuster’s evidence which we found to be of great value in understanding the

socio-economic conditions in Kabul. The only slight caution we have considered

when assessing her evidence, which is in no way a criticism of it, is to note

that the returnees that she has had direct or indirect exposure to are a very

small number of those who had been forcibly returned to Kabul in the last five

years, out of the hundreds of thousands forcibly returned from Pakistan, Iran and

the west in the last 12 months alone and that those persons are likely to be in

the most difficult situations to have sought assistance from AMASO (because

those returnees leading a relatively normal life without significant

difficulties in Kabul would have no need to seek such assistance).

55.

Dr Antonio

Giustozzi is a Senior Visiting Professor at the War Studies Department of Kings

College London and was previously a visiting research fellow at the London

School of Economics and Political Science, Development Studies Institute. Dr

Giustozzi has been working on issues in relation to Afghanistan since 2003, at

its peak he would spend about three months a year there, it is currently down

to a few weeks each year depending on work. He has had numerous books and

articles published in relation to Afghanistan and is a relatively frequent

visitor to Afghanistan. The methodology used by Dr Giustozzi depends on the

nature of the project but in general is less reliant on written sources which

there is a shortage of, and relies more on interviews with the government, the

opposition, civil society and opposition parties. Dr Giustozzi has two

researchers or research managers in Kabul and also works with Afghans and

experienced journalists for both contacts and information. He recognises that

sources may have their own agenda and he seeks out as many sources as possible

to compare and test for reliability.

56.

Dr Giustozzi has

given expert evidence in a number of country guidance cases before the Upper

Tribunal and has broadly been found to be knowledgeable with reliable analysis

of the issues, particularly when his reports were limited to uncontentious

facts rather than prepared on the basis of assumptions about a particular

appellant.

57.

In this appeal, Dr

Giustozzi was specifically asked about the Taliban and any risk to the

Appellant from them if he internally relocated to Kabul and whether there would

be any sufficiency of protection from the Taliban in Kabul.

58.

Overall, we found

Dr Giustozzi to be knowledgeable about the Taliban’s activities and modus

operandi in Afghanistan based on his significant experience and work in this

field. We found his written report to be relatively brief with less

explanation and reasoning for the conclusions reached than could have been expected

in the circumstances of this appeal. However, his oral evidence was much

clearer, with more express analysis and reasoning to support his propositions.

We found that he was clear as to where assumptions had been made based on his

experience and knowledge and where there was (or was not) supporting evidence

to the views given. However, there were inconsistencies within Dr Giustozzi’s

evidence which are difficult to reconcile, which we deal with in the specific

evidence sections below and there is a lack of support by other commentators

for some of his conclusions (such as from Borhan Osman (a political analyst in

the Afghanistan Analysts Network who focuses on insurgent groups) on the

existence of the black list and use of targeted hit teams, recorded in the EASO

Country of Origin Information Report “Afghanistan – Individuals targeted by

armed actors in the conflict” (December 2017)). Overall, we found Dr Giustozzi

to have given thorough evidence to which we also attach weight. We pause here

to record that we have attached significant weight to the EASO Country of

Origin Information Reports, which are thoroughly researched and comprehensive

reports from a broad range of sources.

59.

In some respects,

there was an overlap between some of the evidence given by Dr Schuster and Dr

Giustozzi as to the need for or relevance of support networks in Kabul

for employment and accommodation purposes. We pause at this point to note that

their evidence on this issue was not entirely consistent and set out the detail

below in the relevant sections.

60.

Ms Emily

Winterbotham is a Senior Research Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute

in the International Security Studies Department, prior to which she has been a

researcher for the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit and as a Political

Advisor for the Office of the European Union Special Representative. She lived

and worked in Afghanistan between 2009 and 2015 and since then has returned for

five weeks in total for various pieces of work. She has had a number of

papers, articles and reports published and has conducted research for a number

of different bodies, including the UK Foreign Office and Department for

International Development.

61.

Ms Winterbotham

was specifically asked about the security situation in Kabul and to what extent

this is changed since the Upper Tribunal’s assessment in 2012 in AK. In

particular, she was asked about security incidents, casualties and human rights

abuses in Kabul and the willingness and/or ability of the authorities to offer

protection to the population. In addition, specific questions were asked about

the risk of forcible recruitment by anti-government elements; of kidnapping; of

bonded or hazardous labour; and of violence, including sexual violence.

62.

Overall, we found

Ms Winterbotham’s evidence to be of significantly less assistance and carry far

less weight than the other experts due to her approach to writing her report

and giving evidence generally. Although we accept that this was Ms

Winterbotham’s first experience of appearing in the Upper Tribunal as an expert

witness in a country guidance case, we find her approach to this task to be of

concern. In particular, it became apparent from her oral evidence that when

writing her report, Ms Winterbotham approached the task by using material that

she already had available to her and had amassed over the years in her work,

rather than undertaking any specific further investigation into particular

points or checking for updates to or additional sources to the material that

she did rely upon. The material that she had available to her was collected

for a range of different purposes over a period of time which preceded her

instructions and whilst not necessarily irrelevant to the questions asked of

her, was not specifically collected for this purpose nor was it necessarily up

to date or the most relevant material on which reliance could or should have

been placed. In many instances, material relied upon dated back as far as 2008

and 2009, and a significant proportion of sources were from the period before AK

was heard in the Upper Tribunal. There was also an example of a draft article

being relied upon as a source despite the fact it was not the final version

which was published.

63.

It was also clear

during the course of her oral evidence that there were inaccuracies in the

footnotes in Ms Winterbotham’s report and that she had significant difficulty

identifying whether her evidence was her own opinion or whether sourced from

other evidence (both in the written report and in oral evidence). Where there

was a claimed source, some were wrongly identified in the footnotes and many

were not specifically or even generally identified at all for various reasons

which were unexplained on the face of the report and at best only partially

explained in oral evidence. Further, there was at least one instance where it

was not clear whether a source was an editorial or a news story. This is in

contrast to Dr Giustozzi’s evidence during which he could identify sources

(with sufficient generality to know the organisation and level of person within

it, even if not by name) and identify where his evidence was based either on

particular source material or his own conclusions.

64.

In some parts, Ms

Winterbotham also accepted in oral evidence that risks based on particular

characteristics (such as age, which she referred to as her nuance on the facts

of this case further to reports in which the conclusions were much broader, for

example being applicable to men of any age) in parts of her report were

included because they were the particular characteristics of this Appellant,

rather than because there was any supporting evidence or reasoning for that

being separately identified as a risk or relevant characteristic. That

approach is particularly unhelpful in the context of a country guidance case

where general guidance is to be given applicable to many more people than this

individual Appellant and was of particular concern when this was not clear on

the face of her written report. Further, terminology used in the report was

not defined, and used interchangeably, for example, there was a lack of clarity

on whether a reference was being made to an IDP or to a returnee, or both. It

was accepted that an IDP was distinct from a returnee but there were examples

of Ms Winterbotham answering questions about an IDP by talking about

returnees.

65.

This approach to

giving expert evidence in a country guidance case falls below the standards set

out in paragraph 10 of the Senior President’s Practice Direction No 10 (2010)

(set out in full in Appendix D) and the decision of the Upper Tribunal in MOJ

and Others (Return to Mogadishu) Somalia CG [2014] UKUT 442 (IAC), which

we would have expected and consequently significantly reduces the weight which

we have attached to the evidence as we are not persuaded that it is

comprehensive or up to date. For the reasons set out above, we have approached

Ms Winterbotham’s evidence with caution.

66.

However, we do

acknowledge Ms Winterbotham’s extensive experience of living and working in Afghanistan as well as her detailed knowledge of specific areas of work that she has been

involved in and we do take her evidence into account for these reasons.

Evidence on risk

Risk from the Taliban

67.

Before setting out

the evidence, primarily from Dr Giustozzi, of the specific situation in Kabul,

we set out the evidence (also primarily from Dr Giustozzi) as to Taliban

operations and priorities more generally for background and context.

68.

Dr Giustozzi gave

evidence as to the sophisticated structure of the Taliban who have significant

manpower and financial resources. The Taliban is of the view that they are the

legitimate government of Afghanistan and seek to establish their own regime

there with shadow governments and departments, albeit with a decentralised

structure involving multiple centres of power and a weak hierarchy. In some

areas where they are in control (perhaps 40 to 50 districts out of 318 in

Afghanistan), the Taliban have set up a real government, including appointing a

mayor, employing people to run basic city administration and setting up

courts. In contrast where they are not in control of an area, the Taliban

operate underground. The Taliban have extensive physical infrastructure and

staff both in Afghanistan and abroad and the total manpower exceeds 200,000 men

(including paid in support elements), of which 150,000 are fighters (60,000

members of full time mobile units, the remainder are local militias) and on top

of that number Dr Giustozzi estimates there would be a few hundred thousand

sympathisers and unpaid supporters. The Taliban raise revenue through tax on

economic activity as well as raising money from external organisations and

there are estimates that they have a budget of between $1.5 and $2 billion a

year from these sources.

69.

Dr Giustozzi

describes the decentralised structure of the Taliban as including five or six

Shuras (one, that of Mullah Rasul in western Afghanistan is set apart from the

others) which are autonomous centres of power, away from a central leadership and

who operate on their own authority. There are Military Commissioners at

provincial level. There are 10 districts in each province and within those

districts there are individual Taliban commanders. The EASO

Report “Afghanistan – Individuals targeted by armed actors in the conflict”

refers to a single Shura (the Rahbari Shura, also commonly referred to as the

Quetta Shura) and to an ongoing decline in the provincial and district

structures.

70.

The Taliban have

dedicated units at the provincial level (at least one in each province), with a

team of 20 or so Taliban intelligence operatives tasked with hunting down and

executing collaborators. In Kabul, the Taliban have two separate networks.

The first is dedicated to conflicts operations, for example fighters attacking

high-profile targets. The structure of this network is insulated from other

Taliban structures for security reasons to prevent infiltration or complex

attacks being compromised. The second network focuses on collection of

intelligence and routine targeting of wanted individuals, for example two-man

assassination teams, planting mines on cars and other small-scale attacks. Dr

Giustozzi referred to claims that there were a few hundred people in such

networks, including those providing support such as safe houses and

intelligence. Those who carry out specific attacks are normally from outside

of Kabul, often coming from Pakistan, being brought into the city to be

deployed a few days before a planned attack. The EASO report “Afghanistan – Individuals targeted by armed actors in the conflict” included evidence from

other sources casting doubt on the existence of such specific dedicated units

operating.

71.

Dr Giustozzi’s

oral evidence was that these dedicated units each establish their own targets

based on priorities and available intelligence, albeit his written report

referred to evidence from Judge Safi (a Taliban Judge interviewed by one of Dr

Giustozzi’s researchers on 23 June 2016) that priorities were set by the

military leader of each province. His evidence was however consistent on the highest

priority being those who posed the greatest threat to the Taliban - senior

serving government officials, the security services and spies. At a lower

priority level Dr Giustozzi referred to deserters and collaborators although

not necessarily in that order, depending on how you defined both. There are

two types of deserters, those who simply left or quit the Taliban (such as for

personal reasons like a sick family member) and those who defected to the

government, who would be seen as a collaborator. The latter being more serious

but there was a need to discourage anyone leaving and a concern that someone

may become an informant when they left. Collaborators could include all those

who defy Taliban rules or are seen to be in-line with the government. Collaborators

would include all security forces, government authorities, foreign embassies,

the UN, NGOs and anyone passing information to the government about the

Taliban. These collaborators could number several hundred thousand people and

Dr Giustozzi accepted that the Taliban do not have the resources to possibly

individually follow up on all of them.

72.

Although

successful targeting by the Taliban of high-profile targets is their highest

priority because of the impact of such attacks, it is more difficult to achieve

this given that they are the best protected and it involves larger teams of

people, many of whom would be killed in the effort. Dr Giustozzi explained

that as the Taliban believe they are the legitimate government, they need to

demonstrate to the public that they are the legitimate authority whose goals and

regulations are to be respected. It is therefore considered necessary to also take

action against a person of low-level interest when the opportunity arises rather

than named individuals because of the Taliban’s need to show that they are

serious about sentencing people, enforcing their regulations and because it

helps to scare people leading to the collapse of the government. In these

cases, who is killed is less important than the numbers killed, with any

assassinations still making the headlines.

73.

The Taliban

introduced a new system from around 2006, which has been quite mature from

2010, for the identification, warning, trying and sentencing of persons before

a sentence is carried out. Those who are targeted are limited to those who

have already been sentenced by a Taliban court. Once a sentence has been

imposed it remains forever until carried out. It is only those who have been warned

and sentenced who can legitimately be targeted by the Taliban. However, EASO

in their report “Afghanistan – Individuals targeted by armed actors in the

conflict” refer to evidence of violence and targeting based on personal or

local disputes outside of this system.

74.

Dr Giustozzi

describes a “blacklist”, containing the names of around 14,500 people who are

wanted by the Taliban. He has never seen such a list, nor does he have clear

or comprehensive details on the nature and use of such a list and accepts that

he has been unable to corroborate information about the blacklist. The EASO

report “Afghanistan – Individuals targeted by armed actors in the conflict”

also finds no specific evidence to support the existence of or details about

the blacklist, although at least one source was also of the view that the

Taliban does keep a blacklist of priority targets and another that local

commanders may have their own lists but no centrally organised list. Dr

Giustozzi is of the view that the blacklist does exist because of the

information to that effect he has had from the Taliban, because of the known

warnings given to people and because it would be logical to maintain such a

list.

75.

Dr Giustozzi did

not know whether there was a single or master blacklist but referred to a

central information hub in Peshawar, with connected small hubs in Afghanistan

and he presumed that the Taliban would make use of the computers they are known

to have to maintain the blacklist, by using their sophisticated infrastructure

in Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan. Information about the blacklist would be

passed via a courier system, with messages being carried by individuals using

memory or writing.

76.

In his written

report, Dr Giustozzi stated that information about collaborators is exchanged

between all components of the Taliban, excluding the Shura of Mullah Rasul (or

Rasool, both spellings are used, who has its own list) but in oral evidence

stated that it was unknown whether the Shuras coordinate on such matters. A

complete copy of the blacklist would be available to all of the Shuras but not

at a provincial or lower level. Instead, a Shura would only share names of

people on the list who they thought were in their province with the Military

Commissioner responsible for that area. The Military Commissioner would then

decide what names to share at the district level, which would then in turn be

shared with individual commanders in relation to people that intelligence

showed were within that person’s particular area. As a result, an individual

commander would only likely to have a few names from the blacklist, the full

list being unmanageable, a security risk and impractical to carry for use in

printed form. Dr Giustozzi’s evidence was that the blacklist may be given to

members of the Taliban and paid agents (who may get a version of the list) but

it is not likely to be shared with informers. Local Taliban may, with

permission, have access to the blacklist if a request for such access is

justified, for example, to check whether a local suspect is wanted.

77.

It is assumed that

high profile individuals or those who pose a serious danger to the Taliban,

such as spies, are automatically on the blacklist as are wanted people, but for

those at a lower level, they would only be added if they had received two

warnings from the Taliban (which would be sent to or left at the address of the

individual). An individual failing to comply with two warnings would then be

sentenced for the crime of collaborating with the enemy. The sentence takes the

shape of a third letter or verbal communication, passed on to the collaborator

or somebody close to him. A sentence implies that the individual has been

added to the blacklist. Not all of those who received warnings would be added

to the blacklist, as it allowed people an opportunity to change or repent, or

to make deals with the Taliban instead. A person could not be targeted simply

because they were a relative of a person who is a target or a threat to the

Taliban. Dr Giustozzi assumed that the details included on the blacklist would

be a person’s name, father’s name and place of birth as that is the usual way

to identify people in Afghanistan.

78.

Dr Giustozzi’s

evidence on whether a person could be removed from the blacklist was that this

was possible only in one of two ways. First, by death and secondly, by

contribution to the Taliban’s cause in such a way that the individual would be

offered an amnesty. In his written report, he said that sentences issued from

1996 onwards remained valid and would be implemented by the Taliban whenever

possible and that events a significant time in the past would not affect that.

However, the likelihood of a particular target being picked from the blacklist

depends on the Taliban’s operational environment and in oral evidence, he

stated that a person who had done something a long time ago and had a lower

profile would be a lower priority for the Taliban as they would be likely to

pose a lesser risk of damage to them.

79.

Dr Giustozzi’s

evidence described the increasing sophistication of the Taliban’s intelligence

operation and ability to track down individuals, by reference to a significant

number of informers, including agents within the government and the

intelligence services. He refers to government officials’ belief referred to

in an article in 2011 in the Los Angeles Times that even in areas of weak

Taliban presence the Taliban are informed of everything that happens. Elders

in Taliban villages have also confirmed the existence of informers in the local

area but who cannot be identified specifically. The evidence that Dr Giustozzi

relies on from Judge Safi is that the Taliban are able to monitor who enters Afghanistan

that their intelligence has people at Kabul airport and elsewhere who provide

regular reports about new arrivals. Arrivals in small places are easily

spotted, but less so in large cities and people living alone tend to attract

attention because it is highly unusual to live alone in Afghan society.

80.

In terms of

targeting of wanted individuals, Dr Giustozzi’s evidence was that intelligence

is used to track a person’s movements and information is shared if there is

specific intelligence that a person has moved into a different province or area

or that such movement is expected so that a temporary checkpoint can be erected

by the Taliban to stop someone. The Taliban uses temporary checkpoints in such

cases on the roads out of Kabul to identify specific targets based on specific

intelligence about the type of car they would be travelling in and the time of

travel. These checkpoints may also have the benefit of stopping other

individuals who have not been specifically targeted but who, for example, look

nervous or are dressed in a particular way such as to arouse interest or

adverse attention.

81.

Despite this

background primarily from his written report and his conclusions set out

therein, in oral evidence Dr Giustozzi was of the view that unless references

were sought specifically from the Appellant’s home village (which would be

required for stable employment or formally rented accommodation, not

accommodation in a dormitory or casual labour), no one would know the Appellant’s

whereabouts and there would be very little chance that the Taliban would even

know he was in Afghanistan. Taliban informers in Kabul would not necessarily

know that the Appellant was wanted (even if he was on the blacklist).

82.

The EASO report

“Afghanistan – Individuals targeted by armed actors in the conflict”, relying

on an interview with Abubakar Siddique (a senior correspondent specialising in

coverage of Afghanistan and Pakistan and editor of ‘Ganhara’ website), states

that the list of people for whom the Taliban will invest resources and planning

to track and target into the major cities is limited to between a few dozen and

up to a hundred persons. Other than targeting involving personal enmities,

rivalries or disputes, Mr Siddique’s view was that the Taliban would probably

not target lower level individuals or their family members after relocating to

the cities.

83.

As the Respondent

accepts that there is no sufficiency of protection from the Taliban in Kabul,

we do not detail in this decision Dr Giustozzi’s evidence reaching the same

conclusion.

Risk of recruitment to an armed group

84.

In the Afghan

context, there appears to be no agreement about the meaning of forced

recruitment to armed groups, instead commentators refer to mobilisation of

fighters and agreement within social structures for recruitment, albeit with

the use of coercion, duress or force in some cases. There is also the

possibility that the term forced recruitment necessarily applies to children

because they’re not old enough to make an informed choice as opposed to a more

literal use of force for their recruitment.

85.

Dr Giustozzi and

Ms Winterbotham gave evidence as to the traditional method of Taliban

recruitment, which works through family, tribal and ethnic local religious

networks, also using local specialised cells in Afghanistan and significant

recruitment pools in Pakistan. Recruitment would usually be because someone is

a member of a tribal or kinship group and is instructed to join by elders.

Recruitment is not necessarily on an ideological basis but can be through

incentives for individuals (such as protection, cash, motorcycles, mobile

phones and credit for them) as well as through coercion or direct threats. A

person is most likely to be recruited through tribal, clan or family ties. Ms

Winterbotham accepted that there was limited evidence of armed groups using

threats and coercion in order to force individuals to join them in Kabul and

limited evidence of this elsewhere as well, albeit noting that there was a lack

of monitoring information in Afghanistan which meant the absence of documented

instances should not itself justify the conclusion that they did not occur.

86.

In the alternative

to forced recruitment or mobilisation, Ms Winterbotham gave evidence as to

individuals feeling compelled to join armed groups, not limited to the

Taliban. She referenced a significant body of work relating to both developed

and developing countries on radicalisation and recruitment by armed groups albeit

noting that the theories do not necessarily apply in the context of different

countries or conditions. Overall, she stated that whether a person feels

compelled to join an armed group is not a linear assessment but a complex

nonlinear process for which it is not possible to profile individuals. Instead

there are a number of factors or drivers for recruitment which may be relevant,

including social and economic factors (such as lack of social structures, lack

of housing, lack of employment, issues of achieving manhood and desirability of

marriage), economic incentives, status for an individual and an opportunity to

seek glory.

87.

There is also the

possibility of individuals joining armed groups for reasons of protection, or

conversely for honour and revenge in the context of the Pashtunwali code of

honour. Dr Giustozzi argues that the importance of revenge should not be

overstated given that revenge is most frequently directed at an individual,

extending in some cases to male kin but not more general targets.

88.

In addition to the

above, Ms Winterbotham accepted that a person could also choose to join the

police or security forces in Afghanistan for similar reasons, albeit this is a

less attractive option given the significant casualties suffered from these

groups, that salaries offered are lower than those from militant groups and

recruitment into the government forces requires a high degree of vetting.

89.

Ms Winterbotham’s

evidence was that there is greater evidence about children being at risk of